by Elvia Pyburn-Wilk // Oct. 26, 2011

Berlin-based artist Rebecca Loyche is also a staple in Berlin’s growing group of artists-as-curators. She founded, directed, and curated Mitte’s MMX Open Art Venue along with partner Jonathan Gröger in 2010 (the space lasted for only one short year; MMX= 2010), and will be opening a new artist-run space, CoVerlag, at the end of this month. Loyche is currently finishing her Meisterschüler at Braunschweig HBK on a DAAD Scholarship. Her own work, between photography, video, and installation, focuses on perception and communication, apprehending the silence of the banal and attending to the breakdown and even abject failure of language. When so much is seen but so little is heard, Loyche identifies our isolation and alienation and suggests the conditions for connection to occur. By allowing the viewer to look closer and listen harder, she manages to re-route us away from the straightforward or the concrete; instead seeking beauty, irony, and even humor in the most unlikely, and often most artificial-seeming places.

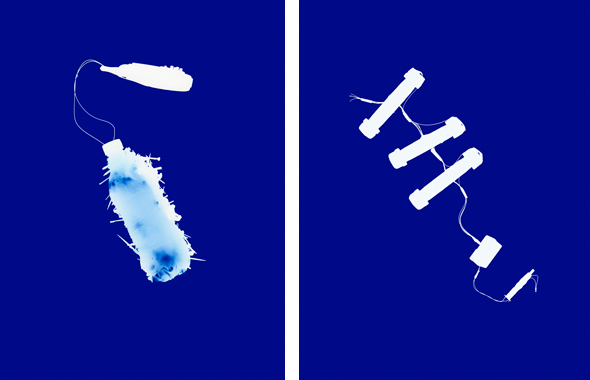

Loyche’s 2008-9 series “Minds/Mines don’t care” are photograms of improvised explosive devices, or IEDs. As images, the IEDs are lonely, clean, and stripped of the grime associated with war. The objects, which Loyche built with the help of a weapons specialist, are made from found materials and simple techniques typical of IEDs made worldwide. By reducing the visual information that would allow us to identify them immediately, Loyche allows the IEDs to become aesthetic objects in their own right, slick and simplified to their contours. And yet in the photograms they remain potent, threatening, and invested with dormant energy. Deciphering the images becomes the work — looking carefully, it is possible to identify cell phone battery packs, pens, water bottles, and cigarette filters. Here is the detritus of an artificial world, tweaked and manipulated to become lethal. These daily, accessible objects are no longer benign but dangerous, and yet as images they linger in a curious state between potential and action, both fragile and threatening at the same time.

I.E.D.s from the “Minds/Mines don’t care“ Series (2008-9), Improvised Explosive Devices, 20×24” Photograms-C-Prints; courtesy Rebecca Loyche

The photogram references the x-ray, inviting us to consider surveillance culture in a broader sense. Increased surveillance both responds to and perpetuates fear; the paranoia that anything could be concealed in someone else’s suitcase is compounded by the paranoia that anyone can look into yours. This ostensible fear of concealed weapons translates to a fear of concealment in general. If western culture is obsessed with transparency in a physical sense, this belies an incredible opacity in terms of communication. To see the inside of an object is not to address the subjectivity that produced it; examining a person’s property does not ask a question and or hear a response. In surveillance societies, the threat of violence is preempted with another invasive act: the search.

In direct comparison to the static, silent images of “Minds/Mines don’t care,” Loyche’s video work “Hvalreki” (2009) likewise points to the failure of communication in today’s world. “Hvalreki,” which means “Stranded” in Icelandic, was shot during the protests following the Icelandic economic crash the end of October 2008. Loyche distilled the hour-long protest speech to a four-minute video that focuses on the sign language interpreter’s real-time translation of the speech and the audience’s reaction to it. Beyond referencing the specificity inherent to Icelandic Sign Language, which only about 200 people in the world use, the piece focuses on a part of the speech describing a national feeling of being silenced. In the translation of the speech we read:

“Geir [the former prime minister] doesn’t know what the people on Austurvöllur are thinking. He’s only human. We’ll send him some q-tips.”

Watching the interpreter sign the motion for “q-tips,” we are confronted with the isolation of spoken language. The ability to hear does not necessitate the act of listening. We are also confronted with a trope that emerges in much of Loyche’s work: the variability of human perception, and therefore the subjective nature of human experience. This is often identified in her artwork via an audio/visual split, or a diffraction of the senses into separated and manipulable channels, which makes the viewer aware of his or her own sensations – and the capacity for their artificial manipulation. This formal argument against a universal subjectivity reminds us that the human body cannot be conceived of in terms of input and output.

“Hvalreki“ (2009), a 45-minute protest speech edited down to 4 minutes based on the tone of the speakers, the emotion of the sign language interpreter and the crowds’ reaction; Courtesy Rebecca Loyche

Human biology is foregrounded in Loyche’s 2010-2011 installation “Circadian.” The installation, which can be translated in differing iterations to various sites, envelops the viewer in a white room of full-spectrum light, the effects of which mimic the effects of sitting outdoors in the sun. A soundtrack playing in the room lasts about fifteen minutes, which is the minimum length of time that the body needs to physically respond to sunlight. The piece takes its name from the Circadian rhythm, the natural human cycle corresponding to a 24-hour day, which is governed primarily by amount of daily exposure to sunlight. While the viewer may experience a sense of disorientation or even isolation upon entering the space, after fifteen minutes the light should elevate mood and increase energy levels. Full-spectrum light, which has in other contexts been used as a depression treatment therapy, slightly changes the appearance of people in the installation room, and incrementally alters the body’s daily and seasonal rhythm. In this way, the piece poses complex questions about what is artificial and what is natural, and asks us to think about how our bodies live in and respond to our constructed environments.

It is difficult to identify the room “Circadian” occupies as either domestic, private, public, or institutional space. This is partially because it literally brings the outdoors inside, creating a false source of sunlight in an enclosed area. This division between programmatically-defined internal and external spaces is further explored in Loyche’s video work series “Still Life I, II, and II” (2011). The videos each present a still life scene in silence upon a table against a window. Suddenly, debris begins dropping into the scene accompanied by loud noises of destruction. We can’t see what is being destroyed, but from the emerging light and sound from a busy street outside, it becomes clear that one of the room’s walls is being knocked down piece by piece.

Still from “Still Life“ (2011); courtesy Rebecca Loyche

The “Still Life” videos present the audience with several oppositions, the most important being the interior space where the action is occurring versus the outdoor space beyond the wall. This dichotomy is intensified by the manipulated audio track that accompanies the action, which has been modified to amplify the urban noises from the public street beyond the wall. This interior/exterior split suggests a congruous split between natural decay and forceful destruction, returning us to the question of artificiality. The still life scenes begins and ends in “natural” stillness, but this is overcome as the wall is forcefully destroyed. The strange, detached implication of violence in this act implies a threat of danger even in the most domestic or banal situations. Like an IED, a bomb made from household materials, the still life scenes confront us with the latent fear of the everyday. And like the hand-made explosive, or Iceland’s economic collapse, the disaster that occurs in the video is entirely human.

The still life scene takes place in an old apartment in Berlin, a city whose rapid destruction, re-building, re-appropriation, and re-inhabitation make it an important site for the examination of memory in relation to physical space. In another video project entitled “Art Fair” (2011), Loyche examines one component of Berlin’s emerging culture based on its transitory global population, the phenomenon of the art fair. For the project, the same video of a scene shot during ArtForum Berlin was shown to three specialists: a psychologist, a security officer, and an art dealer. The experts were each asked to analyze the video according to their areas of expertise. The psychologist examines the body language and mannerisms of the subjects as they walk through the hallway between gallery booths; the security specialist focuses on individuals who look suspicious or potentially threatening; the art dealer checks for signs that could identify a possible buyer. The video is displayed with three simultaneous audio channels that the viewer can alternate between, comparing the ways in which the three voices size up the ArtForum audience according to their particular agendas.

In a triple layer of voyeurism, the audience at the art fair becomes the subject of observation by the three invited observers, who in turn come under scrutiny by the viewer of the video in the gallery space. This ultimate viewer is given an unusually privileged vantage point from which to examine human behavior, inferring as much about the three commentators as can be inferred by watching the scene. As is usually the case when we act as voyeurs, we realize the extent of our own exhibitionism, and the extent to which our daily lives depend on watching and being watched.

Still from “Art Fair“ ( 2011); courtesy Rebecca Loyche

Besides being a portrait of the nuances in judgement that govern human social relations, “Art Fair” expands upon Loyche’s critique of surveillance culture, and of a subtle paranoia produced through constant observation. The ArtForum scene was filmed on an iPhone, ensuring that no one walking through the scene acted differently or felt suspicious in a way beyond the normal suspicion we must always feel in our constant-camera society. This paranoia or suspicion of observation is the same that arises in a world where a ballpoint pen or a battery pack could be concealing an explosive device. It is in this way that much of Loyche’s work is sensitive to the contemporary moment, to the potential for danger in the tension between biology and artificiality. The difficulty of demarcating the line between “nature” and “artifice” – a dichotomy that has arisen out of fear that the former is being lost – combined with the threat of concealment, however imagined or real, turns all observing into searching.

How does the artist’s role as observer change when observing as searching is a primary cultural activity? Loyche seems to suggest that we must observe ourselves observing, looking at the act of looking itself. In her thoughtful pieces, Loyche does not underestimate the power of human perception, she instead allows us to perceive slowly, and to formulate our own responses.

Additional Information

Co Verlag

Opening Reception: Friday, Oct. 28; 4pm-11pm

co-verlag.com

rebeccaloyche.com

Torstraße 111, Berlin, click here for map

Writer Info

Elvia Pyburn-Wilk is an artist and writer based in Berlin. She received her BA in Sculpture from Bard College and is currently the assistant at Studio Lukas Feireiss, a multidisciplinary curatorial practice investigating the intersections between architecture and art. Elvia runs an experimental publication called Eaders Digest and her writing has been featured most recently in the book Testify! The Consequences of Architecture, which accompanies the exhibition by the same name at the Netherlands Architecture Institute in Rotterdam, Netherlands.