This essay is part of an exchange between Revista ARTA online and Berlin Art Link. Editors Cristina Bogdan and Alison Hugill commissioned 3 texts each, on themes relevant to the art scenes of both cities. In the series, our contributors explore the socio-political nature of painting, music & performance, and DIY/underground art spaces in Berlin and Bucharest. All texts are published in both magazines, and are available in both English and Romanian.

Article by Valentina Iancu in Bucharest; Tuesday, Oct. 27, 2015

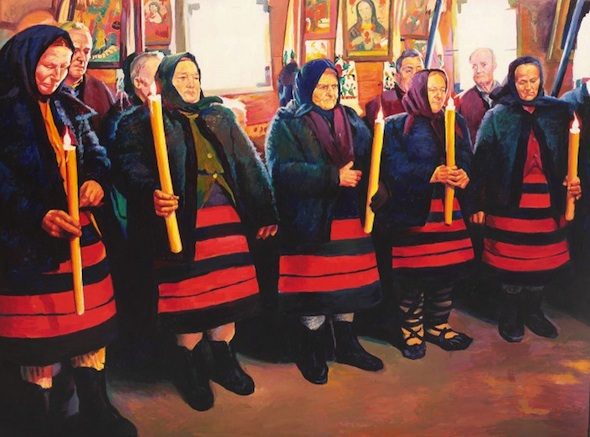

Dumitru Gorzo – “Vigil” (2006), acrylic on canvas, 130 × 174 C; Photo credits ARTMARK

Dumitru Gorzo – “Vigil” (2006), acrylic on canvas, 130 × 174 C; Photo credits ARTMARK

The death of painting, which was emphatically announced after 1935 and has been repeatedly acclaimed in modernism, post-modernism, while still debated in some artistic mediums, is becoming an actual problem in the new capitalist cultural geographies of Eastern Europe. Being an instrument of communist propaganda, painting is mistrusted by the avidly reformed artistic community of the 90s, with many painters radically transforming their routes once the political regime shifted. The entire Romanian cultural establishment is affected by the transitions and is forced to reform or at least change the appearance. Painting is declining. On the other hand, paintings are still produced, exposed and massively historicized. “The queen of the arts” entered the 21st century unchanged, with its same old obsolete poetics, its dusty narratives and a sick addiction to the past. There was a boom in the so-called 2000s generation, which has become established in the meantime, and then it became a repetitive mimicking. The exhibited paintings in the last years in Bucharest, almost exclusively in commercial galleries, appear to be part of an obsessive “neo”- any type of Western style whose resources have long been depleted, contain nothing brand new, as the painter Adrian Ghenie so rightfully puts it: “I have a feeling that today’s painting is basking in a weird type of mannerism, and there is no talk about a radical new painting yet.”

During the first years of the political regime shift, the local context is apparently unfavorable for paintings, seeing as the “political urgencies of those times, the need to quickly adapt to anti-communist activism and pro-capitalism ideologies, the competition between new medias, all of these seemed to definitely invalidate painting’s capacity to say something profound about the new human condition and to adapt to the new world formed in Romania, as well as the entire Eastern Europe, due to the difficult overlapping of a tenaciously virulent communism with a new and ferocious freedom.” Suffocated by its own limits and manners, Romanian painting begins to decline after the 1989 revolution. At the same time, conceptual art and new media are of interest because they have not been very affected by the compromises imposed by the 20th century dictatorships. In this context, the western debates on “the death of painting” become more and more relevant for the Romanian space.

The end of the 20th century coincides with the beginning of the neoliberal capitalism that distinguishes itself through a strong reconfiguration of the values of contemporary art. The Romanian artist has universal aspirations, he desperately awaits any western validation and, in order to achieve it, starts to imitate western styles and practices. Romanian painting becomes a huge sponge that absorbs any idea that has the potential to open new visual directions to explore. In this transitional moment, which is a creative boom after all, painting is no longer interesting to the point that it feels useless, as the Cluj gallerist, the founder of Plan B gallery, Mihai Pop says: “whoever painted was stupid.”

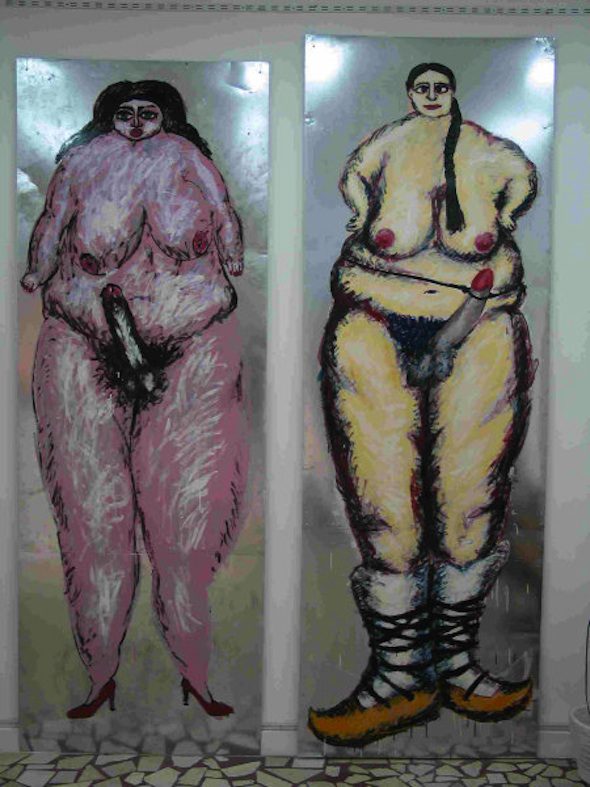

Dumitru Gorzo – “Chicks with Dicks” (2003), oil on aluminum sheet; Photo credits H’Art Gallery

Dumitru Gorzo – “Chicks with Dicks” (2003), oil on aluminum sheet; Photo credits H’Art Gallery

The following decade destabilized this myth. A new type of thinking, mostly borrowed from the west, began emerging once commercial galleries started popping up: “capitalist” realism (Magda Cârneci) or “lifestyle” (Erwin Kessler). A few young graduates from The National University of Art in Bucharest are trying to generate a new visual discourse that is capable of “rehabilitating” the status of painting. When compared to the universal scene, the revolution of Romanian painting is just a synthetic transformation based on the assimilation and remaking of many western experiments: abstract expressionism, Pop Art, Neo-Dada, CoBrA, Young British Artists, photo- or hyper-realism etc.

The 2000s generation becomes visible with the help of the first commercial galleries in Bucharest that opened after the year 2000. With them, the art market grows, but the majority of these artists finish university without real possibilities of exhibiting this type of painting that is different from the manners that survived from the last years of communism in the local scene. These artists are radical, they crave newness and change. A lot of them have signed on works that are visually fascinating, full of emotions and stories. Others looked for answers to political, philosophical or historical problems. They brought a new energy in the contemporary scene than managed to revive painting. What is interesting is the fact that the established painters of this generation have very clearly defined and distinct personalities, with the common denominator being their predilection towards the figurative.

The Rostopasca group (1997-2001) integrates painting in a performative process with a lot of dada nuances. Even though the Rostopasca artists walked a road already paved by the western world, they bought a new life on the local scene that led to the necessary revolution in order to unwind the young painters. The Rostopasca gang – Angela Botnaş, Nicolae Comanescu, Dumitru Gorzo, Alina Penţacm, who were later joined by Alina Buga, Mona Vătămanu and Florin Tudor – changed the visual language that was already tired of gesturalism and neo-orthodoxism and that automatically transformed the way painting is perceived. Amongst the artists that made their debut within the revolutionary avant-garde group, Nicolae Comănescu, Angela Bontaş and Dumitru Gorzo remained loyal to painting. While Gorzo is looking to overcome the limits of the pictorial support by often replacing the canvas with fretted wood, Nicolae Comânescu makes paintings in the classic sense of the term. Both of them activate within the figurative realm and their themes are inspired by everyday life. Dumitru Gorzo’s subjects often come from the rural universe of Maramureş, his birth place which is filled with beauty, a place he always carries within himself. Peasant women wearing traditional outfits in various poses, sacred images treated in an interesting dialog with popular icons, images of contemporaneity, these are just a few of the most interesting themes that Gorzo played with throughout the years. Nicolae Comănescu, on the other hand, handles subject that are apparently unassuming and a lot more serious due to their social and symbolic content. He is an urban explorer, he observes the city and its many specific issues: marginal neighborhoods with grey, crowded buildings (Berceni), patrimony buildings that have been illegally demolished by the real estate mafia (Assan’s Mill). At a formal level, the most interesting experiment produced by Nicolae Comănescu was painting with a refined substance made out of improvised pigments that he gathered from near his studio (which was in an apartment building in Berceni): dust, dirt, ashes, mustard, etc.

In the year 2000, an adopted son of Bucharest, born in Basarabia, made his debut at the Romanian Museum of Literature: the painter Roman Tolici. He wipes out all of the visual effects that confer painting its sublime and ever so dusty pictorial quality. He is graphic, flat, fresh and very relaxed. His photographic simplification has a fresh and contemporary feel. The images he picks out using his own personal system with a photo camera, are then painted on the canvas without the use of a projector. He draws and paints out of passion for the creative process, whose specific and traditional means he respects. “This way, I can truly translate using my own language what the world offered me through the camera lens, transforming it into an iconic message” the artist writes. Tolici’s images are part of a radical and transgressive, sometimes violent, other times a banal and playful thematic realm.

Roman Tolici – “Hypostasis 8 (The Gospel After Santa Claus)” (2006), oil on canvas; Photo credits Roman Tolici

Roman Tolici – “Hypostasis 8 (The Gospel After Santa Claus)” (2006), oil on canvas; Photo credits Roman Tolici

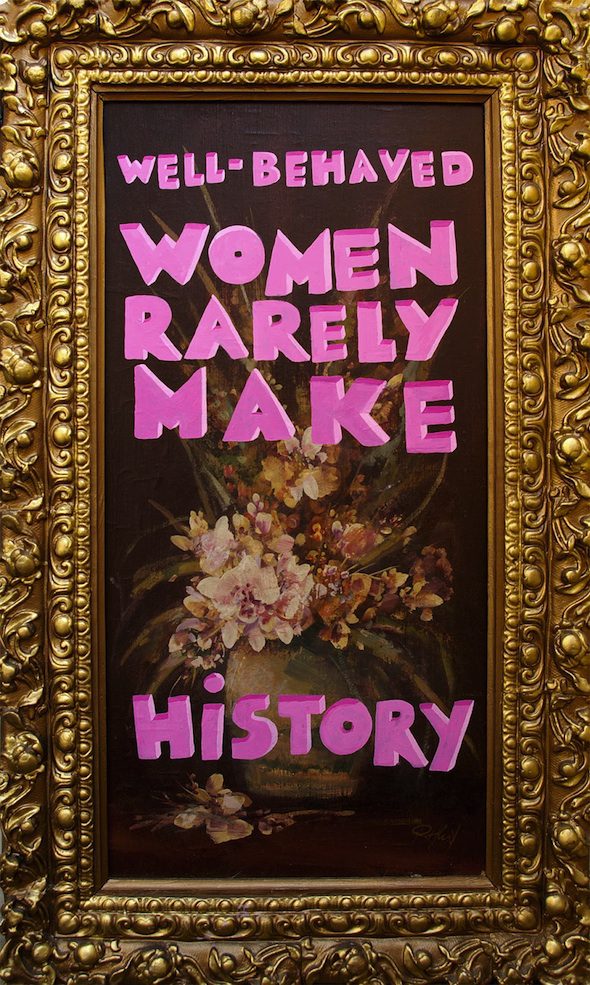

Contemporary Romanian painting is produced in a micro patriarchal society; its main representatives are men. I have a feeling it is the only artistic field that follows the patriarchy so closely. If we look at the institutional validation, the MNAC exhibitions or the teaching staff at the University of Arts, the masculine dominant becomes problematic and disturbing. Roman Tolici, Gorzo, Comănescu and Gili Mocanu are established Bucharest painters that found validation via ample personal shows hosted at MNAC. This is probably not a conscious marginalization of women artists, but rather a continuing of old habits out of a convenient inertia. For example, Suzana Dan or Anca Benera, two 2000s generation artists that have a lot to offer in terms of visual, are incomparably less visible than their male counterparts. Often using a very current feminist vocabulary, Suzi Dan proposes an aggressive-transgressive type of painting that could be seen as a distant relative of contemporary Neo-Pop. Suzi produces surrealist imagery using imaginary, semi-fantastic props that cause paradoxical effects: it’s violently suave, it is a calm and warm aggressiveness.

The 2000s generation painting, with its established representatives: Nicoale Comănescu, Florin Ciulache, Suzana Dan, Dumitru Gorzo, Roman Tolici, Gili Mocanu etc. is viewed with enthusiasm, collected and very consumed in the cultural scene. Future generations have seen this revolution as a path that should be followed. The Bucharest art scene has changed considerably in the 2000s, there are many more galleries now. In recent years, painting becomes the center of attention in the art market and leaves the cultural, alternative scene behind. There is a lot of painting, a lot of exposure and a lot of selling. Good or bad, beauty is in the eye of the beholder.

Suzana Dan – “Sadness is Looking at Me” (2009) and “Well-Behaved Women” (2007); Photo credits Suzana Dan

Suzana Dan – “Sadness is Looking at Me” (2009) and “Well-Behaved Women” (2007); Photo credits Suzana Dan

The bachelor and masters exhibitions at the University of Art and the commercial galleries are now filled with figurative paintings. Many young artists are influenced by local or Cluj based artists and end up losing their personality and doing banal works. They form a collective that produces art where the influences are more visible than the personality. The value of their work is questionable. What we know for sure is that these works make the 2000s painters, as well as the UAD graduates that are known under the enforced name of the “Cluj School”, even more valuable. Today, figurative painting seems to be getting closer to self-obsoleting via overproducing/inflation.

A lot of young painters that follow this visual trend become more and more diluted due to the almost mechanical reproduction of the internet’s unlimited photographic resource with the use of the projector. Their choices are often questionable. The thematic is quiet, flat and mostly repetitive and uninteresting. Although it is intoxicated by platitudes and endless repetition, painting is still being quietly consumed out of inertia. The polemics of painting rage on; same with the production of paintings. Of course, there are a few interesting painters within the younger generations. The feeling of anticipation lingers.

___________________________________________________________________

Valentina Iancu is an art historian and researcher. She works at the National Art Museum of Romania. Her research focuses on aspects of Romanian modernity related to the political realm, East European surrealism and the rhetoric of young contemporary art.