Article by Alice Bardos in Berlin // Saturday, Apr. 16, 2016

The thought of a sneeze, the touch of an unwashed hand or any form of contact with microbes that can cause illness usually causes people too recoil, but Nonhuman Subjectivities, on now at the Art Laboratory Berlin, boldly respects and elevates our conscious understanding of these living inhabitants of our bodies. There may, in fact, be a greater ratio of microbial life than human cellular life in our own composition, which is why this collaborative exhibition explores these organisms as agents in a tightly knit relationship with their hosts, as well as the population as a whole. Via photography, mechanics, mapping, as well as controlling colonial shapes, what becomes apparent is that humans have a lot to learn from microbes even on topics as complex as feminism.

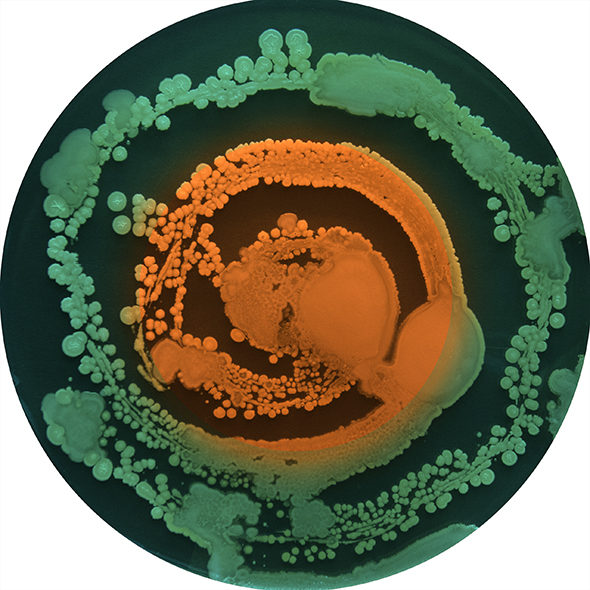

Joana Ricou: Other-Self Portrait, 2016 // Courtesy of the Artist and Art Laboratory Berlin

Joana Ricou’s ‘Other Self Portrait’, is a photograph of a bacteria taken by swabbing her belly button. It destabilizes the notion of perceiving ourselves to be alone when without the company of macro-life. The beauty of her painted-over photographs of the cultures, arranged in a swirl formation, even evokes pride that our bodies could potentially be hiding life so curious to our creative minds. Perhaps it also inspires viewers to question what further powers of our inhabiting bacteria we might be missing.

When pressing your finger to the button on ‘Mycophone_Unison’, an electrical current is shot through the contraption to the celestial plate and then finally to the micro biomes of bacteria collected from artists and scientists Saśa Spačal, Mirjan Švagelji and Anil Podgornik. Through these materials the electricity is harnessed to produce signature sonic pulses which depend on the characteristics of the colonies. Unlike the cellular life of our bodies, which is dictated by our own genes, microbe cultures can change much more drastically. However, this installation highlights the idea that there is still an individual relationship in each person’s organic identity to their microbial life. The machine also hints at the influence that people can have on each others’ composition.

Saśa Spačal, Mirjan Švagelji and Anil Podgornik: Mycophone_Unison, Installation, 2013 // Courtesy of the Artists and Art Laboratory Berlin

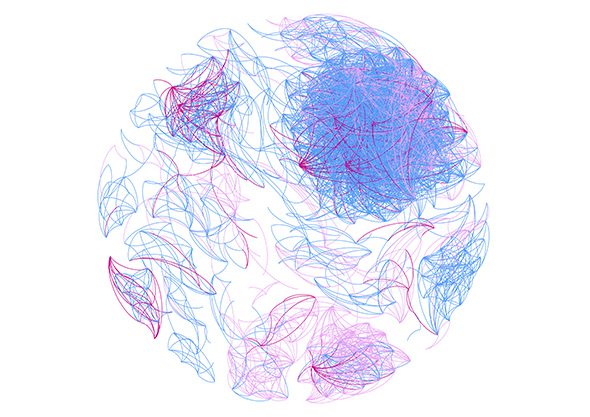

This is a note which is elaborated on by François-Joseph Lapointe’s 1000 Handshakes. The project had it’s inception during this year’s transmediale, at which time the artist shook the hand of 1001 people and collected samples at intervals of fifty hand shakes. The results where later sequenced and maps of the different bacterial relationships were made. Though they are presented without the contextualization of tables or numbers, the progression of maps illustrates how complex the networks of different forms of life are, even just on the surface of the skin of people at the time all under one roof. The first few images have the appearance of a small root network of a plant, moving on from there the groupings appear to disperse and then centralize which superficially seems to mimic the movement of a jellyfish–and with it the notions of interconnectivity and diversity. It is astonishing that the same subconscious questions we have when introducing ourselves to new people are mirrored in the secret ties that our microbes have to each other. These works seem to ask: ‘What ties us together in spite of our differences? Is there more difference than similarity between us? Is that indicative in anyway of danger?’

François-Jospeh Lapointe: Microbiome Selfies, Colour Print on Paper // Courtesy of the Artist and Art Laboratory Berlin

Tarsh Bates‘ work with Candida parapsilosis is a meditation on what happens when this type of curiosity turns to an accepted fear and leads to issues of stigmatization and even discrimination. In a series of acrylic boxes, the artist has grown a culture of Candida atop agar and the artist’s blood in an almost Victorian pattern, which was actually inspired by the first rendering of its relative, Candida albicans, made in 1853. The piece, entitled ‘Surface Dynamics of Adhesion’, attempts to attract viewers to the Candida fungi family, which is more often associated with infection in women, promiscuity and uncleanliness. Arranging this culture to grow in almost a wallpaper type pattern questions why yeast is perceived so negatively when connected to women, in particular despite the facts that men also contract the same infections, and that similar microbes are used in the baking of bread. To confront this issue Tarsh Bates even once baked bread using Candida–which in such high temperatures is killed–and served it up to some hesitant recipients.

Tarsh Bates: Surface Dynamics of Adhesion, Installation, 2016 // Courtesy of the Artist and Art Laboratory Berlin

Her political curiosity with Candida does not stop there. She also concerns herself with our connections to our ecosystem. The artist told me that through a mechanism called quorum sensing Candida can sense when its colony is growing too large to sustain itself and changes its gene expression accordingly. The feature helps the fungi increase its likelihood of survival but can also act as an analogy for human presence on our planet. Speculation can then be made about why such simple life is more able to live within the restrictions of its circumstances, while humans are carelessly depleting resources and altering the surrounding ecosystems.

In school, many people were taught that complexity increased with evolution, placing humans atop some imagined hierarchy, however scientific discourse is changing about these constructs and Nonhuman Subjectivities helps to illustrate this point. The complexity of microbial life can help to teach humans not only about their own ways, but also about how they occupy the world. Perhaps, if there is one idea from school with which we should approach microscopic life, it’s to respect the organisms that have lived before us and even consult them when trying to address the bigger issues in our world such as identity, agency, and politics.

Exhibition

ART LABORATORY BERLIN

Collaborative Show: Nonhuman Subjectivities

Exhibition: Feb. 27 – Apr. 30, 2016

Prinzenalle 34, 133359 Berlin, click here for map