The Venice Biennale 2017 series offers previews of curatorial and artistic projects presented in the context of this year’s biennial art event.

Dublin-based artist Jesse Jones will be Ireland’s representative at the Venice Biennale 2017. Her work, titled ‘Tremble Tremble’, attempts to address the rise of current social movements in Ireland.

Jones’ practice crosses the media of film, performance and installation and, for her exhibition at the Biennale, she proposes the return of the witch as a feminist archetype, who has the ability to alter reality. Often working in collaborative structures, she explores how historical culture may hold resonance in our current social and political experiences. Berlin Art Link caught up with Jesse Jones to get her take on the role of witches, the state, the church and the law within contemporary society.

Jesse Jones // photo by Tessa Giblin

Lisa Birch: How will the national pavilion at the Venice Biennale act as a site of ‘alternative law’, as you describe it?

Jesse Jones: In the artwork I have made for the Irish Pavilion, I’ve thought about the idea that a National Pavilion is a sort of cultural arm of the state, therefore it could be the site to pose a fictional alternative to the law. ‘Tremble Tremble’ proposes a superseding law that I have devised, called “Utera Gigantae”. The artwork proposes that an older law than the law of the state might reside in the body itself. This older law aims to turn the body into the site of political agency, rather than continuing the current legal reality of a woman’s body being controlled by the constitution in Ireland.

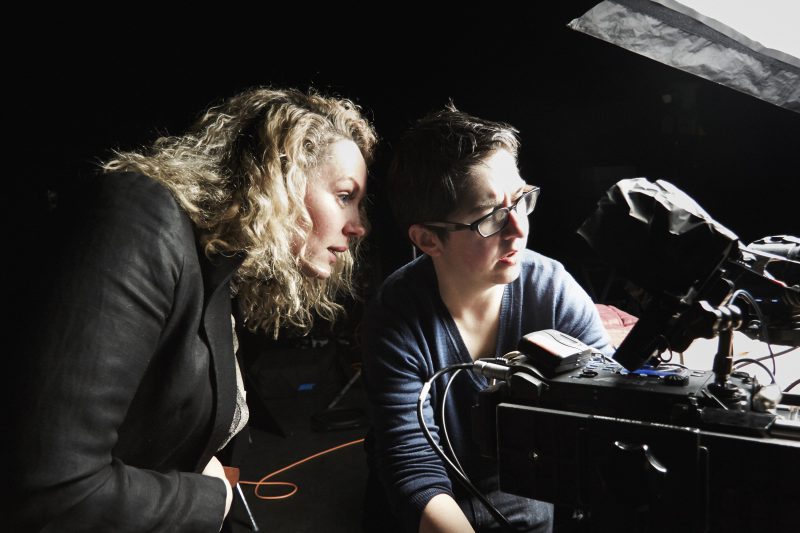

Jesse Jones and Emma Dalesman // photo by Tessa Giblin

LB: Your work is entitled ‘Tremble Tremble’ and is inspired by the 1970s Italian Wages for Housework movement, but the work itself is influenced by current political shifts in Ireland, which have seen demands for a transformation between the relationship of church and state. How do you feel these two quite separate progressions are intertwined?

JJ: I feel that they are definitely connected in terms of a political consciousness and the continuous thinking of the Left: the Italian Left, in particular, where its feminist movement has made its mark on the kinds of political thinking that is influencing Ireland and elsewhere. One of the most significant points of departure for ‘Tremble Tremble’ is the work of Silvia Federici, an amazing activist and writer whose work, such as ‘Caliban and the Witch’, is influencing a new generation of anti-capitalist feminists. Federici was involved with the Wages for Housework movement in the 1970s, and it was in reading her work on the structures of capital that I discovered how the home, the family and the role of women in society are all connected. These political systems of control allow us to understand why something like abortion (which was legalised in so many European countries decades before) is still illegal in Ireland today, through the complex relations between the church, state and capitalism, and our arrival at modernity through the process of being the colonised subject. In a way, the current feminist movement in Ireland has now reached this historical impasse between the state and possibilities of freedom and autonomy that might have dominated social movements in Europe after the 1960s. I would argue that, because of our very special relationship with colonialism, we are arriving at that possibility today. Therefore, it is vital to make historical comparisons and link to struggles that can inspire and inform our rising, contemporary feminist movement.

‘Tremble Tremble’, 2017 // Photo by Ros Kavanagh

LB: Your work explores historical instances of communal culture and how they hold resonance in our current social and political experiences. In which ways can you see that the law has influence over what is considered to be socially acceptable throughout different generations?

JJ: Simply put, we only have to look at the law itself to see that. In Ireland, marital rape was legal until the 1990s. How does that affect how we think about rape, culturally? How do we think about what conditions make it acceptable to rape a woman? If it is legal to rape your wife, and she is your property, you even own her body and sexuality. This is not some mad 1860s law, but something women in Ireland lived with until the 1990s, so it has shaped our contemporary subjectivity. Its spectre is still present in how women feel the law protects them when it comes to this issue. In terms of abortion, despite the law, attitudes are changing, but it is this residue of law and illegality that prevents an open cultural understanding of what it means. This prevents women from speaking about their experiences because, by law, they could be arrested, which creates a huge influence over what is acceptable within our culture. We have to combat this at a cultural level in order to change the law.

‘Tremble Tremble’, 2017 // Photo by Ros Kavanagh

LB: Why do you think the demand of the separation between church and state is currently taking place in Ireland and how has the demand for change arisen?

JJ: Ireland has a church-state relationship due to its emergence as an independent nation in the 20s and the 30s after it came out of a violent civil war following centuries of colonization, where the church was a stabilising factor in public and political life. In fact, a counter-revolution successfully created a Catholic theocracy. Irish people lived under this for generations, and it was upheld by the loss of our young people who were choosing to move away for economic reasons. However, this all came to a head following the 1990s boom in the 00’s economic crash. A highly educated, worldly and independent generation that stayed in Ireland came out of this moment, and continue to see different possibilities. They are asking questions about the nature of the state, and they don’t feel the religious ties to power, and want a different society. It is a very exciting time.

LB: Your work envisions the image of a witch as a feminist archetype and disrupter who will be able to transform reality. How do you feel this symbol of a witch is relevant to today’s social battles?

JJ: I feel like we need more disobedient bodies and disrupters, and a return of archetypal exiles. Across Europe, we are seeing some of the same forces of misogyny and capitalism that were rampant in the persecution of women in the 16th and 17th century. The witch has never really gone away, but women’s power has been suppressed. Our culture is genuinely fearful of types of representation of women as it destabilizes our culture that is built so fundamentally on sexism and hostility towards women. As an artist, I see the witch as a force of agency, that flies in the face of this. I claim the witch as a force of generative subjectivity as she is an archetype that can awaken our histories by destabilising and pulling at the roots of capitalism in a very deep way.

‘Tremble Tremble’, 2017 // Photo by Ros Kavanagh

LB: Your work aims to imagine a different legal order, one in which the multitude are brought together as a mass to proclaim the new law of ‘Utera Gigantae’. If achieved, how do you perceive this new law to be?

JJ: The work proposes a giant woman’s body as a force beyond the state; this is a very clear metaphor for collective power of the mass, or a multitudinous body. I believe that a feminist social movement can change the law and question the state itself. To do this, first, we must be disobedient to the law on mass, to not follow it, and make it strange to our bodies. This is what is happening in Ireland today, and represents the shift of the political imaginary in its stages of transformation into absurdity. When the state becomes absurd to the multitude, it can no longer survive as it relies on a credibility to harness our reality. This metaphorical female giant can destroy it.

Exhibition Info

LA BIENNALE DI VENEZIA

Jesse Jones: ‘Tremble Tremble’ for Irish Pavilion

Curator: Tessa Giblin

Exhibition: May 10 – Nov. 26, 2017

Arsenale, 30122, Venice click here for map