Article by Beatrix Joyce in Berlin // Wednesday, Feb. 14, 2018

Premiered on February 8th at Sophiensaele, Naoko Tanaka’s installation performance ‘Still Lives’ transformed the theatre into a mystical landscape filled with creeping shadows and rotating spotlights. As if operating a great machine, Tanaka and her collaborator Yoshie Shibahara animated various contraptions and mobilised their set design: a cloud of translucent plastic was held aloft by bubbling air and manipulated by rubber balls; tumbleweeds zoomed down a suspended thread that cut through the entire space; and the black, shiny stage surface reflected the lop-sided furniture that the two women gracefully positioned on the diagonal. Upon speaking with Tanaka about her work, it was revealed that the title ‘Still Lives’ holds a double meaning. It can be read as both the plural of “still life,” referring to the style of painting, and as a shortened version of “it still lives,” pointing towards her performative interest in metaphorically bringing objects to life. Tanaka shared more of the ideas behind ‘Still Lives’ with Berlin Art Link.

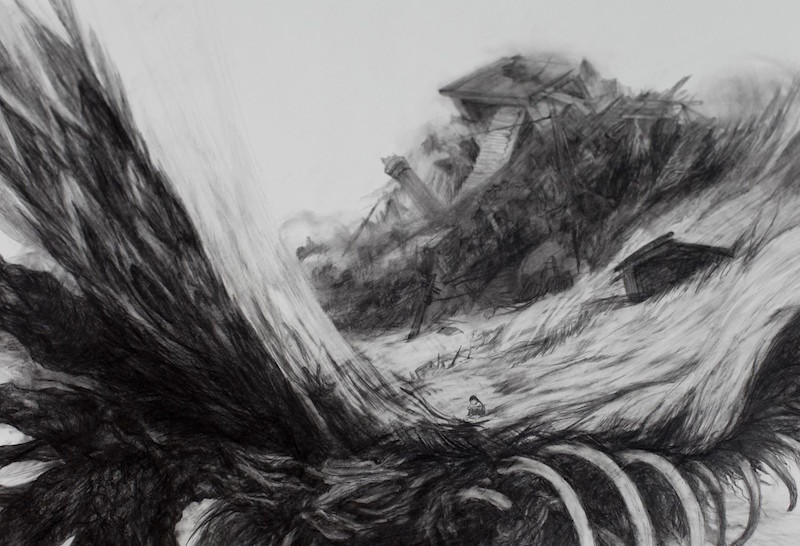

Naoko Tanaka: ‘Still Lives,’ 2018 // Photo by Henryk Weiffenbach

Beatrix Joyce: What struck me most about ‘Still Lives’ was its presentation within a traditional theatre format. Installation and performance hybrids are usually presented at galleries or in site-specific locations—places not traditionally connected with performance. How do you experience the ‘staging’ of an installation performance?

Naoko Tanaka: I am always thinking about how I can adapt my pieces to different spaces and work with different architectures. Although it is a theatre, Sophiensaele has a long history, as it is a converted ‘Handkraft’ workshop. There are so many people that have passed through its doors, each imagining and dreaming within its walls. This is what I feel when I am there. With the “reverse waterfall” I attempted to capture this shared imagination and pull it all the way up and across the empty tribune.

BJ: Your performance presence was natural rather than theatrical, yet you performed within the norms and etiquette of the theatre. How do you conceive your stage presence?

NT: This is always a dilemma. I called ‘Still Lives’ a szenische installation (“staged installation”). I have no training in dance or acting, my background is in fine art. It is important, with any medium, to use good tools, but if I were to use young, fit, trained dancers, it would not result in quality for me. My objects are not perfect; they are broken and they have a human touch. I think my own, naive, personal way of handling the objects is hereby instrumental. If the performer does not know the story behind the object, it becomes empty. Yoshie and I know what we need to do and why. Our performance presence is, in this way, born out of necessity rather than theatricality.

Naoko Tanaka: ‘Still Lives’, 2018 // Photo by Henryk Weiffenbach

BJ: During the performance, the focus gradually shifted from one action to another, as if by cause and effect. Each action was hereby given a great deal of time. What are your thoughts in regards to the pacing of the piece?

NT: I think it is important to give the spectator time to imagine. I always try to think of the images that are born and that grow in the eye of the beholder. I try to see and imagine—not understand—how it is for them. I hope that with the creation of artistic time, the spectator can feel his or her own time as well. However, the objects within the performance each have their own time span. For instance the rotating light—I call it Licht Uhr (“light clock”), as it should turn around in a constant rhythm—is independent and functions through a non-experiential, mechanised process. Once activated, the objects determine how long it takes us, the performers, to do things. In this way we are in dialogue with the objects, as we exist on equal plains.

BJ: In what way do you work with narrativity? Is there an overall narrative to the piece?

NT: My intention with ‘Still Lives’ was to make a series of images, which I hold clearly in my mind. Initially, when the images come to me, they are not yet accompanied by an action, so I have to figure out how to go from A to B. For me this is a very big task as it requires rigorous self-analysis. The images emerge from my subconscious and I don’t know why. I have to find out afterwards. In terms of narrativity, it’s like prose or poetry. The piece consists of connected fragments, which are puzzled together. There is no script. The images do not fit together in an overarching storyline, but rather they each have their own “time inside.”

BJ: Are the objects like characters?

NT: The objects are like themselves. It’s a European tendency to anthropomorphise. In my work, however, I am not so keen on ascribing certain characters, roles or personalities to particular objects.

Naoko Tanaka: ‘Still Lives’, 2018 // Sketch courtesy of the artist

BJ: How much does your heritage influence your work? Do you actively make references to Japanese culture?

NT: Since my time at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, I always try not to use, in an easy way, my origins. With Yoshie I speak Japanese, but she has also been in Germany for the past 20 years. In this sense, we are in a very similar position and we are careful to speak with each other about what the cultural reading of the images may be. For me this questioning results in a kind of dualism, as I have both European and Japanese influences inside of me.

BJ: To what extent are you interested in creating a meditative environment, which instills a quiet and focused state of mind?

NT: I read once that nowadays the average amount of time a viewer spends in front of an art work in a museum is 12 seconds. In my work, I am always searching for this moment of alertness, where you are very awake and your senses are engaged. This is difficult to achieve if the energy in the space is not concentrated towards the performance. If someone has 60 minutes of attention for your artistic world, that is fantastic! In this way, the norms of theatre allow for a strong, centralised focus on the performance.

Naoko Tanaka: ‘Still Lives’, 2018 // Photo by Henryk Weiffenbach

BJ: How was it, as an artist who usually works alone, to collaborate with Yoshie?

NT: I invited her into my artistic world. We shared very similar viewpoints and modes of observation. However, we experienced some difficulties in the early stages of the creation process. The first ideas you have always feel stupid or naive. When I am working alone in my atelier I can experiment freely because nobody knows what I am doing. Although it might feel boring and like nothing is happening, this time is important. But with a collaborator, you must articulate your ideas and you are hereby already shaping and changing them at a very early stage. You have the pressure to give meaning to this boringness and to give some direction to what you are doing. This was something new for me. I asked myself how I could still do things that felt meaningless or stupid with a partner by my side.

Artist Info

Writer Info

Beatrix Joyce is a performance artist and dance writer based in Berlin.

storiesinmotion.de