Article by Jess Harrison in Berlin // Saturday, Mar. 17, 2018

Through her work, the artist, reiki teacher and lifelong student of metaphysics Melissa Steckbauer seeks to increase possibilities of intimacy and communication by emphasizing the ecstasy of everyday human experience. Her latest exhibition, ‘The Sonancy of Falling and Standing Repeatedly,’ deals with the discourse around notions of community and sensuality, relating to the concept of “radical softness,” which was developed by American activist and artist Lora Mathis. Radical softness is an idea and internet-based aesthetic that relates to the strength of sharing your emotions to combat the societal stigma of feelings being a sign of weakness.

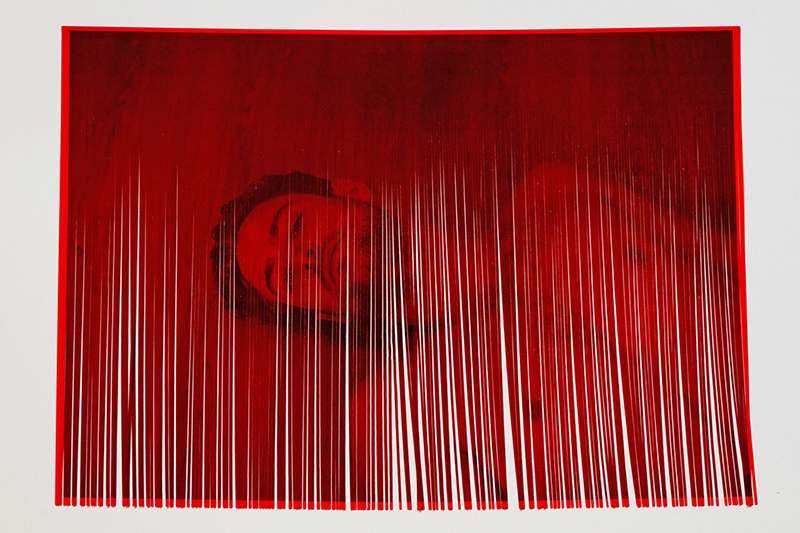

‘Sensorium’ in collaboration with Paul Philipp Heinze, Linards Kulless, Christoph Mühlau, J&K (Janne Schäfer and Kristine Agergaard), Magda Tothova, Suse Wächter, Latvian Center for Contemporary Art, 2016 // Photo by Atis Jakobson

Texts by feminist, nonbinary and pro-BDSM poets, writers and philosophers also accompany the exhibition that will be on view at Galerie im Turm starting on March 22. Alongside the show is a participatory performance programme that will see the gallery transform, across different evenings, into a reading circle and discussion space. Ahead of the show opening, the Berlin-based artist sat down with Berlin Art Link to discuss notions of human connectivity, using sensory experience to provide an alternative kind of exhibition space, and why we should wear more purple hats.

Jess Harrison: Could you briefly introduce the ‘The Sonancy of Falling and Standing Repeatedly’ exhibition and perhaps outline a few of the motivations behind it?

Melissa Steckbauer: The exhibition is more or less a sensorium. It will have sonic and aromatic elements and the principle idea is that connectivity is possible when people feel relaxed and comfortable. It’s a challenge to create a comfortable environment in an exhibition space because I think most people are a little bit protective in such environments, but we are going to try anyway. Sylvia Sadzinski [the curator of the show] said she wanted to do something alive, and I was like, “Yes me too, let’s do something alive,” opposed to just objects in a space.

Melissa Steckbauer & J&K (Janne Schäfer and Kristine Agergaard): ‘Outliers’, 24h, an ƒƒ project, 2014 // Photo courtesy Teatr Studio, Palace of Culture and Science

JH: Art is often associated with the visual, yet this installation is a sensorial playground, with, as you mentioned, auditory, olfactory and tactile levels. Why do you think it is important to stimulate all the senses and particularly privilege the tactile? What dimension do you think it adds for a visitor in an exhibition space?

MS: I think that no matter what city I’ve been in I’ve always felt a bit uncomfortable in these gallery or exhibition environments and I think this probably doubles for people who aren’t in the art world. So just on a very basic level, I wanted to create a space that people would want to come into. Then I thought about how people would feel once they were inside. Do they feel good there? I wanted there to be something about the environment that stimulated the body as well as the intellect. Experiences when they are at a high-functioning, visual level might cause an effective connection, but this is often intellectual; you resonate with the things that are on display in a way that reinforces your value system.

It doesn’t necessarily have anything to do with play or pleasure, which I am attracted to. Our culture doesn’t often present moments for us to explore this, to feel comfortable, and I think what we miss is that which has nothing to do with money or prestige or access. I tried to focus on objects and experiences that are readily available to us, such as the smell of the grass or the feeling of dancing in the rain, all of which have tactile or auditory dimensions. I then wanted to make this available to other humans, this comfort, in a way that is not privatised, but is in public space.

JH: So the show is about taking ordinary, everyday experiences and bringing them into the gallery space, because it’s something people can associate with.

MS: Even if it doesn’t make any one else feel comfortable, these are the things that for sure I feel comfortable with, and I can imagine that is possible that other humans are missing these things too. It’s about a basic closeness with others in a grounded capacity and the ability to feel in the presence of other humans. This notion of affective tissue, or connection with other humans, is usually on a one-to-one basis but I find that when the door is opened for collective experience, even just a little bit, amazing things can happen. It’s to do with the tiny slices of ecstasy that are available to us on a regular basis. I can only take my own bubble as my example, but I know this is something that people in my world use as fuel.

Detail during the installation of ‘‘The Sonancy of Falling and Standing Repeatedly’ // Courtesy of the artist

JH: The installation is described as using quilts and feathers, which are materials and mediums that could be associated with traditional feminine domesticity. Why did you choose these materials? Do you associate with this notion of arts and craft or the craftivist movement?

MS: Somehow we managed to find all the material supplies for the show and all of the foam is recycled. As far as my relation to the notion of craft goes, I am more attracted to the overarching field, the affective tissue between humans, why people are moved to do things which do not reiterate their own cultural value system but for some other reason which has nothing to do with prestige or external power systems. I’m not attracted to the predominant cultural value. There are humans, who aren’t even members of a community, who are doing things with their hands. They maybe won’t have access to the cosmology that you and I might share, the art knowledge or the things we are collectively educated to believe are important to art making. There are people outside that frame who are producing things all the time and those folks are doing interesting things. They may be coming from a crafting or quilting background or even putting things together with pieces of bread and spit. There are truly wonderful things going on in the world. I am attracted to what people are creating in worlds we are not educated to believe are the principal and the most important.

JH: Texts by performance artists and writers such as Alok Vaid-Menon and Patrick Califia accompany the show. Why did you choose to include these texts and how do these people relate to your work?

MS: All of the writers I have included, I believe, are wonderful humans. The transgressive nature of their being-hoods and how they stand strong in their voice make it easier to be the weirdo that I am, however modest my weirdness is. I first read Patrick Califia’s work when I was a teenager and it strongly influenced me. Patrick is a like a fairy godfather to the trans community and to the BDSM community. He also talks about how to be a parent and how to deal with taking shit from the human world. The things he has to do to protect himself are crazy. Alok is a similar character—I don’t think many people would be able to handle the things they have to do and deal with to just to be a human alive in this world on a daily basis. Of course this is just the nature of things, and this is why you don’t have as many icons from that community who have survived to be in their 70s or 80s. I wanted to make a new space for these amazing human beings who are just being human.

JH: So do you see the show as a sort of safe space, or a space of protest? Or do you mediate between the two?

MS: I prefer an affirmative condition to one that is contra or critiquing something. It is much more difficult to take a position which I full heartedly believe with and stand with, whether it be it a soft position or a delicate position. These things are harder than critique. Through this notion of affirmation, I seek to move past language into some other elemental part of what it is to be an organism and try to calibrate with all the communities and things I am influenced by. This kind of affirmation is less a part of the cultural framework, it’s a less enforced position.

JH: This seems so at odds with a lot of particularly very recent art, which is intended to critique existing social and political structures.

MS: If you claim something you enjoy and you stand in it, it can be a scary move. You can see it even in the clothes we wear, it is the reason why most people wear black. It’s safe, its filtered, we’re inside culture. We are not wearing feathery blankets, cardboard boxes or even bright purple hats. I could be having a lot more fun with my physical experience but I’m not.

JH: What about your wider body of work? You moved from a focus on painterly portraits to photography and collage, and now this sensory exhibition. What sparked this change of medium?

MS: The great thing about Berlin artists is that everybody is doing everything. There’s no rule which says this is how you identify this is what you do. I don’t even think that the work in this show is that different from my previous stuff; I think it’s just a matter of showing more parts of oneself. If we wore those purple hats and the feather blankets, it would just be more information about us than we are previously making obvious to the world. As soon as you step outside of the frame and share that kind of information with the world you put yourself at great risk but that’s the only way it makes its safer for other humans. I’m taking an incredible advantage of the risks that other people have made and am trying to fit into frames that are bigger than the frames that came before. Ultimately that’s the thing to do—the sexy and interesting thing to do—but we don’t always make time for it or want to face the repercussions. It must start somewhere though, even if this just means putting on that purple hat. Because if we can’t do that then how are we going to shift the big paradigms that are about heteronormativity or value of capital?

Exhibition Info

GALERIE IM TURM

Melissa Steckbauer: ‘The Sonancy of Falling and Standing Repeatedly’

Opening Reception: Thursday, Mar. 22, 2018

Exhibition: Mar. 23 – May 13, 2018

Frankfurter Tor 1, 10243 Berlin, click here for map