Article by Samuel Staples // May 16, 2018

In his multidisciplinary practice, Brussels-based artist Emmanuel Van der Auwera explores the topics of reality vs. simulation, the trivialization and desensitization to violence, communication and the framing of messages, and the recording of and responding to catastrophic events. His current exhibition ‘Blue Water White Death’ at Mu.ZEE in Oostende, Belgium includes what he calls “VideoSculptures”, pieces from his ‘Memento’ series (2016) and the film ‘Missing Eyes’ (2017).

More than part of the exhibition title, blue is also the color of the pieces comprising Van der Auwera’s ‘Memento’ series, which presents newspaper panels used in offset commercial printing on aluminum. Here, Van der Auwera isolates parts of the plates before exposing them to light, capturing certain images and text while burning away others. The results are ghostly white traces of images and texts over blue canvas. Much like some news media these days, the artist presents altered realities using images originally taken as the documentation of these events. In this way, he provides a compelling mediation on the way we live and communicate now.

BAL spoke with Van der Auwera just before the exhibition’s opening about the show as well as the unveiling of a new VideoSculpture, to be presented at the inaugural show of the Kanal Centre Pompidou Museum in Brussels.

Emmanuel Van Der Auwera: ‘Nuit Americaines,’ installation view, 2018 // Courtesy of Harlan Levey Projects

Samuel Staples: What is the meaning behind the title of this exhibition and what can it tell us about your work?

Emmanuel Van Der Auwera: ‘Blue Water White Death’ is the name of an early 70s shark film that earned cult status. Jamie Stewart and Jonathan Melburg then used it as the title of their experimental album. Appropriation is one aspect of my work, and the title offers hints of subjects and stories, which are touched on in the exhibition by pulling on certain aesthetic aspects of the works: the blue sea of the newspaper offset plates beneath the elevated image of a grieving crowd; the blue whale that never actually appears in ‘Wake Me Up at 4:20’ and the white lights of a sculpted set of screens that literally project images through absence. There are other tangential references. For example, we can smell the sea from the museum’s front door.

Coming from the documentary approach, I address the ethical position of the author and viewer when it comes to engaging with pre-existing context and topics. I feel an ardent need to engage with the world, sometimes investigating extreme manifestations of obsession and taboo. I believe that our contradiction as a society and culture needs to be addressed and confronted. What expands beyond relative morality, self-serving narrative and ready-to-use technologies is, for me, where the membrane of humanity lies. I want to engage sincerely with the world and reflect on the human experience in the present time.

Emmanuel Van der Auwera: ‘VideoSculpture (O’Hara’s on Cedar St.),’ 2016, installation shot // Courtesy of Harlan Levey Projects

SS: Many of these works explore the trivialization or desensitization of violence as seen through mass media. What do you think these can tell us about the relationship between performative violence and the media landscape?

EVDA: The exhibition focuses on society’s desire for the spectacle of horror, how media creates political narrative around tragedies through multiple filtering processes. It also deals with how we try to control the chaotic nature of history by picturing it as a political spectacle. By multiplying the point of view, we try to “catch” the event in its “authenticity,” and this weakens the basic notion that reality and fact exist outside of the realm of images, representation and ideologies. What is at stake behind the crafting of an image or a trend on social media or in the news? What is the human technology that triggers collective response? Where is the common ground when concepts like reality and fact are quickly becoming relative?

In a world where everything turns into spectacle and image, where our eyes are becoming equally voracious and numb, we have to educate ourselves to be a responsible and wise audience. The viewer should be aware of the responsibility that goes with the act of seeing. This era requires the audience to be critically active and engaged.

SS: The differing versions of truth and the question of what is real and what is simulation seem to be recurring themes in your artistic work. Can you tell us more about these relationships?

EDVA: Media forms us as we form media. “Fake news” is as old as news, but the speed, reach and potential of opinion manufacturing has infinitely increased. Democracy becomes as dizzying and speculative as the stock market; an ability or at least attempt to read between the reflections is needed. A philosopher would put this in words, I try to bring an audience into the world those words would create and generate works, which demonstrate that viewing is an active task that comes with the same kind of civic responsibility as driving a car.

Works in the ‘Memento’ series use the tomb of the newspaper to mark passing moments of time. They are made with the materials, tools, processes and employees of the newspaper. Everything about this work is real, including the frustrating truth that when it comes to events, we only ever get a glimpse at fractions of the thing we think we’re seeing. The simulation happens before I arrive. My work memorializes it.

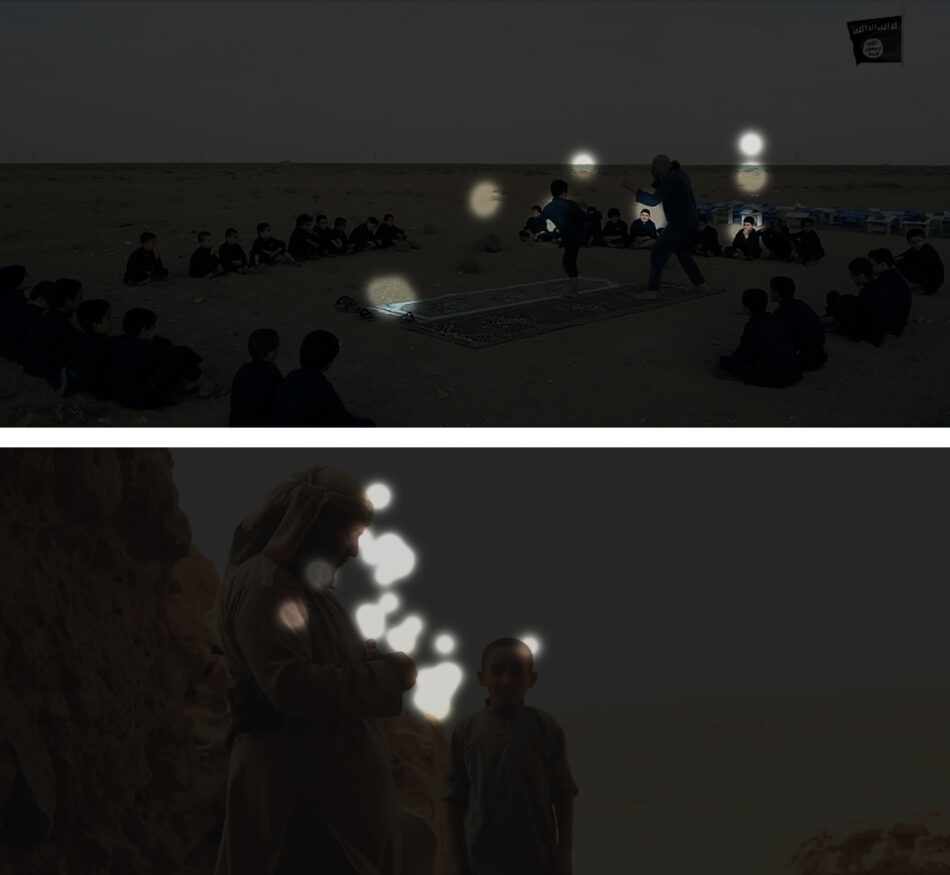

Emmanuel Van der Auwera: ‘Missing Eyes’, video stills, 2016 // Courtesy of Harlan Levey Projects and Emmanuel Van der Auwera

SS: Much of your work could be perceived as a commentary or criticism on the way we communicate and interact with one another in contemporary times. What do you make of the notion of online community? And how do you deal with this in your practice?

EDVA: People behave with strangers like they would with good friends. There are perversions of intimacy, rights of passage, a dizzying access to information locked into so many floating bubbles. It’s an incredible window into the human soul. Online communities feed my practice both in terms of research and material. The films ‘Missing Eyes’ and ‘Wake Me Up at 4:20’ deal with this topic, and so does my approach to carving into LCD screens. ‘Missing Eyes’ is the third film in a trilogy, which began with ‘A Certain Amount of Clarity’ and was followed by ‘Central Alberta,’ and it is a journey into an online community and their conversation about taboo, extreme images, censorship, suffering and ideological bias. In ‘Missing Eyes,’ instead of portraying individual participants as the first two films had, eye tracking data from willing viewers of a film are used like a flashlight; the gaze of the audience determining what the next audience sees as points of concentration are illuminated like flickering lights. In some ways, the audience that helps develop the artwork saves its audience from the original footage.

Installation view of Emmanuel Van der Auwera, 2018 // Courtesy of Harlan Levey Projects

SS: Can you tell me more about the VideoSculpture that you will present at the Kanal – Centre Pompidou and how it relates to your practice?

EDVA: This work is similar to those at Mu.Zee—the absence of an image is revealed in its reflection. This gives the perception of watching the negative of a film that seems to play in a visible underground. The content is from a short film that I made titled ‘Shudder.’ It’s constructed of stock images; generic fiction used for a variety of purposes from documentaries to TV dramas.

Additional Info

This article is part of our monthly topic of ‘Community’. To read more from this topic, click here.

Exhibition Info

Mu.ZEE

Emmanuel Van der Auwera: ‘Blue Water White Death’

Exhibition: May 12 – Sept. 9, 2018

Romestraat 11, 8400 Oostende, Belgium, click here for map

KANAL – CENTRE POMPIDOU

Group Show: ‘Kanal—Centre Pompidou A Prefigurative Year’

Exhibition: May 5, 2018 – June 2019

Quai des Péniches, 1000 Brussels, Belgium, click here for map