Article by Sarah Messerschmidt // Jan. 31, 2019

‘For Your Eyes’ is Palestinian-American artist Jordan Nassar’s debut exhibition in the Middle East, with a solo show at Dubai’s The Third Line. Having grown up in New York City, Nassar’s works function as a means of looking toward his cultural heritage, while simultaneously contemplating the role of cultural imaginary for diaspora communities. He draws on a long tradition of Palestinian craft, working with a distinctive lexicon of patterns, motifs and embroidery techniques, yet developing something recognisably his own. Each work is hand-stitched, the result of carefully-honed skill and a meticulous attention to detail, yet the products often feature more organic forms of colour that interrupt the otherwise formulaic arrangements of his work. Mountainous, warm-toned and layered, symmetrical patterns give way to sumptuous landscapes, evoking visions of Palestinian topographies. With this synthesis of pattern and form, Nassar achieves a multi-dimensional representation of the Middle East, in effect examining the concepts of heritage and home from the dreamlike perspective of someone whose cultural identity is developed at a distance.

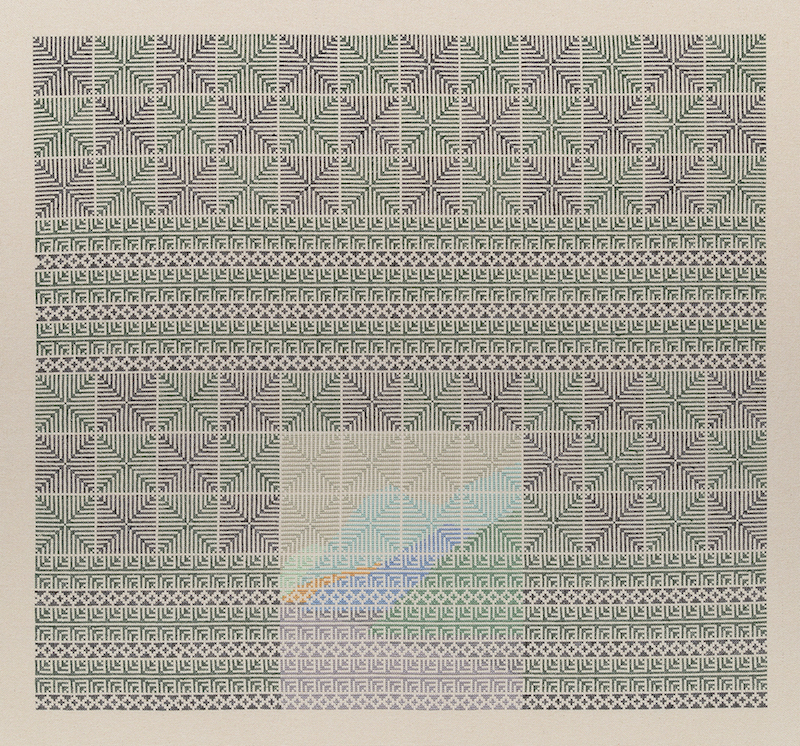

Jordan Nassar: ‘Memories’, 2018, hand embroidered cotton on cotton, 85.09×91.44 cm // Courtesy The Third Line

Sarah Messerschmidt: How did you come to embroidery as a means of exploring Palestinian heritage and cultural identity? Was it a skill you already had, maybe passed down through a relative, or did you learn to embroider to suit the subject matter of your work?

Jordan Nassar: I started embroidering at a time when, I think, I was searching for a way to connect to my Palestinian heritage. I grew up really torn between the standard pro-Israel stance of Upper West Side New Yorkers and my father’s strong and very vocal pro-Palestinian position. When I was young, this resulted in my avoiding the topic entirely, not knowing whom or what to believe. A trip in the year 2000 to the West Bank with my family resulted in more confusion as, upon coming back to NYC and simply telling my friends about what I’d seen in really dire places like Hebron, I felt attacked by my NYC peers, called anti-Semitic simply for describing the realities of the occupation, and so on. This further closed my mouth and mind with regards to Israel and Palestine.

In 2011, however, I met Amir Guberstein, who is Israeli and who would become my husband, and within a few months we travelled to Israel together. This was the beginning of my learning about the situation for myself, by going there and actually experiencing it, on both sides, for the first time. Over the next few years, we’d go to Israel a lot, and while there I would also go visit family and friends in Palestine. I think that, at that time, as I started to explore and actually in some ways appreciate Israel, I started to yearn for a connection to Palestine, maybe partially out of guilt, maybe partially out of just wanting to align myself a bit more on the ‘side’ I was born into. Having always been a crafty kid, doing things like origami and crochet, one of the first things I thought of with regards to something Palestinian was this kind of embroidery, which was ubiquitous in my family home growing up, as is common with levantine Arabs. It just seemed like something fun and interesting to do, so I picked up a needle and thread, and did a lot of research about the history and meanings embedded in this medium… and the rest is history. So, unlike 99% of the Palestinians that do this embroidery, I was not taught by my mother or grandmother. However, I still feel that the act of doing it is a very Palestinian act, as incorporating this practice into one’s daily life is something many Palestinian women do and have done for generations.

Jordan Nassar: ‘For Your Eyes’ detail, 2019 // Photo courtesy The Third Line

SM: I understand that in Palestinian embroidery, patterns can be very specific to where they come from. Can you describe the use of patterns in your work? Are they adapted from more traditional artisanal patterns, or have you developed a lexicon specifically your own?

JN: Yes, one of the features of Palestinian embroidery is that each town, village, and region has symbols that are distinctly theirs, that can identify them to others when an onlooker sees one such symbol on their clothing. It’s an unfortunate truth that, in the 21st century, much of the nuance and differentiation between symbols and regions has been lost: partly a result of globalization, partly a result of the displacement and occupation of the Palestinians. However, there still is some amount of that identification left in the symbols.

When I began working with this embroidery, it didn’t feel right to me to use symbols that would identify me as being from Bethlehem, or from Ramallah, or from Jerusalem, as I’m from New York, and so I did develop my own lexicon. However, as the years have gone by, and as I’ve spent so much more time in Israel and Palestine, and as my work has developed from an idea to more of a way of life, I’ve let go of this concern and now freely use symbols from all over. In another case, when I did the Artport Tel Aviv artist residency in Jaffa, I made a body of work using all symbols from Jaffa. I will say that the one major difference between my work and traditional Palestinian embroidery, with regards to patterning, is not in the symbols themselves, but in the application of those symbols in a space. For example, whereas in a dress you might see one row of a Cypress Tree motif as a border, I make pieces with stacks of rows of the same Cypress Tree symbol, forming a heavy rectangle or square. So, the symbol is traditional, but the application is my own.

Jordan Nassar: ‘For Your Eyes’ detail, 2019 // Photo courtesy The Third Line

SM: For this exhibition, you have collaborated with craftswomen living and working in Hebron. What changes about your practice when you collaborate? Did this collaboration in particular help to bridge the modern and traditional?

JN: Yes, I worked with women from the Hebron area, as well as women in the Daheshe Refugee Camp in Bethlehem. This collaboration started out as an experiment, of course, but over time has developed into a body of work that I’m really excited about. The pieces have a landscape, which I embroider, inset into a field of traditionally-colored patterning, which they embroider. I like to think of the part of the pieces that the women embroider as a ‘background’, both in terms of setting the stage for a color palette for a piece, as well as their traditional use of patterning and how they apply colors to the patterns as a historical ‘background’ that I can then juxtapose with my landscapes. It’s a very stimulating collaboration, where I send them a layout of patterning in black and white, they do their part in colors of their choosing, and then when I receive the piece back, missing a chunk, I use the colors they’ve chosen as a starting point to work off of as I embroider a landscape in the empty space, completing the pattern. I do think the aesthetics of these pieces bridge the traditional with my new way of using this medium, and I’m so excited by the visuals that we’ve been achieving with these works. The show at The Third Line is the first exhibition of these collaborative works, however there are currently a few up at James Cohan Gallery in NYC as well, in a group exhibition.

Jordan Nassar: ‘For Your Eyes’ installation view, 2019 // Photo courtesy The Third Line

SM: This is your first solo exhibition in the Persian Gulf region. Is there a difference to you in presenting your work in the Middle East versus America, and perhaps more specifically, New York?

JN: There is absolutely a difference. In America, I have a very basic goal with showing my work: I wish to bring the viewers into a conversation about the complexity of the reality in Israel and Palestine. Just to understand that, it’s complicated, full of nuance and grey area. That’s it. Simple. I’m not trying to sway anyone’s opinion, though I do believe there is a clear right and wrong here. What bothers me about the perception of Israel and Palestine in America, or the West, is that people somehow treat it as a black and white issue; a simple, this-is-right-and-this-is-wrong kind of thing. All I want people to understand is that there is a contradiction to everything they think about Israel and Palestine. Sure, there are illegal settlers and angry protesters, but there are also mixed half-Palestinian, half-Israelis, there are Palestinians and Israelis working together in business, coming together for group therapy, helping each other. Living together. I just want people to understand that it’s complicated.

In the Middle East, however, I feel like this is less of an interesting conversation to have because they’re much closer to the situation. It does still have value, of course, but I do think people are a bit more aware of the realities on the ground. Maybe I’m wrong in assuming that. But anyway, I find that my experience as a second-generation Palestinian-American, and explorations of the effects of diaspora, is an area that is a bit more unique and interesting to an Arab or Middle-Eastern audience, and so in a way I focused on that with this show and these works. The juxtaposition of the traditional embroidery style with my ‘outsider’ way of doing it.

Jordan Nassar: ‘For Your Eyes’ detail, 2019 // Photo courtesy The Third Line

SM: You describe your work as finding the intersection between language, politics, cultural heritage and ownership, but also ‘post-internet visual language.’ How does the latter connect to the other themes? Do you think of your work as political?

JN: Cross-stitch embroidery is classified as a counted-stitch embroidery, meaning that it is on a grid. When going along with the colors of the traditional patterns, it doesn’t really matter, but when cutting through the patterns with colors and making landscapes, or any other type of pseudo-figurative ‘painting’, the grid starts to really effect what you can do—the squares are basically pixels, but super analog. The original pixels. So, in that sense there’s a relationship to computers and the internet, and there is something very contemporary about the way the landscapes are set into the patterns in these works, as though you dragged and dropped something on a computer. I suppose that’s what I was referring to with that description.

Of course, language enters into things because the symbols carry meaning and identity. Identity brings us to cultural heritage and ownership: ownership of culture, ownership of issues, public fury at artists discussing issues that aren’t ‘theirs’, and the converse of that, my feeling that—as a Palestinian who is also Jewish (due to a recently discovered family mystery on my Catholic Polish side) and married to an Israeli—I have a responsibility to discuss this issue because it is my issue. I am “allowed” to discuss it and feel, therefore, that I must. So yes, I do consider the work political, but the work itself is not overtly political, other than the simple fact that it is a Palestinian medium. I consider it more of a tool with which I can start conversations I want to have. Show my work, and immediately we’re talking about Palestine and Israel.

Exhibition Info

THE THIRD LINE

Jordan Nassar: ‘For Your Eyes’

Exhibition: Jan. 16–Feb. 27, 2019

Unit H80, Alserkal Avenue, Dubai, United Arab Emirates, click here for map