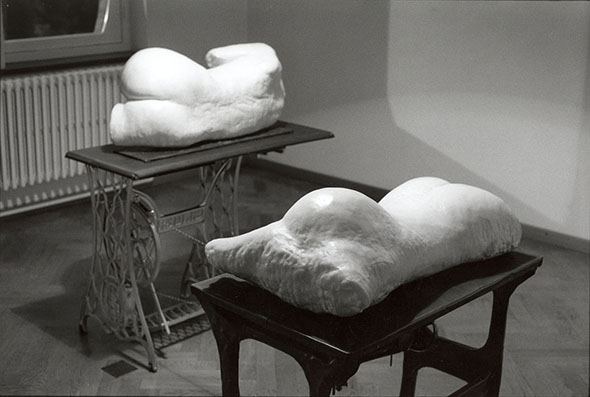

“Salome” (1990), Cast silver, 35 x 13 x 15 cm

“Salome” (1990), Cast silver, 35 x 13 x 15 cm

Interview by Elizabeth Feder in San Francisco; Friday, Dec. 07, 2012

Introduction

As much art arguably should, Flemish artist Jan Van Oost’s work conjures up some complex and conflicting responses. Delicate and exquisite treatment of materiality used to render images and figures of morbidity draws one in with simultaneous curiosity and revulsion. Oost is speaking from another era, drawing his inspiration from the expressive energy of 19th century Belgian symbolists like Antoine Wiertz, Léon Spilliaert and James Ensor. In contrast to the increasingly prevalent wave of digital and new media arts, Oost anchors himself in a tradition of confronting materiality while pushing contemporary questions of subjectivity and the thin line that exists between beauty and atrocity.

In anticipation of his first solo show, The Demon Love, opening on December 15th at Galerie Rolando Anselmi in Berlin, Berlin Art Link got a chance to talk with Jan Van Oost about the roles of desire, obsession, fear and death in his work.

Interview

ELIZABETH FEDER: Much of your pieces evoke an ever-presence of death, while tapping into a more personal, 1:1 scale expression. What first captivated you about the death-in-life narrative?

JAN VAN OOST: The moment one starts to reflect about life, one enters the realm of philosophy: mortality is a key subject-matter. Escaping from the mystic lie that is “Life after Death,” my aim is a modern self-consciousness. Even from early on, my art has accumulated the many ways that only death completes the process of being alive. What is the meaning of life? Who am I? Asking these questions frames the issue of our existence.

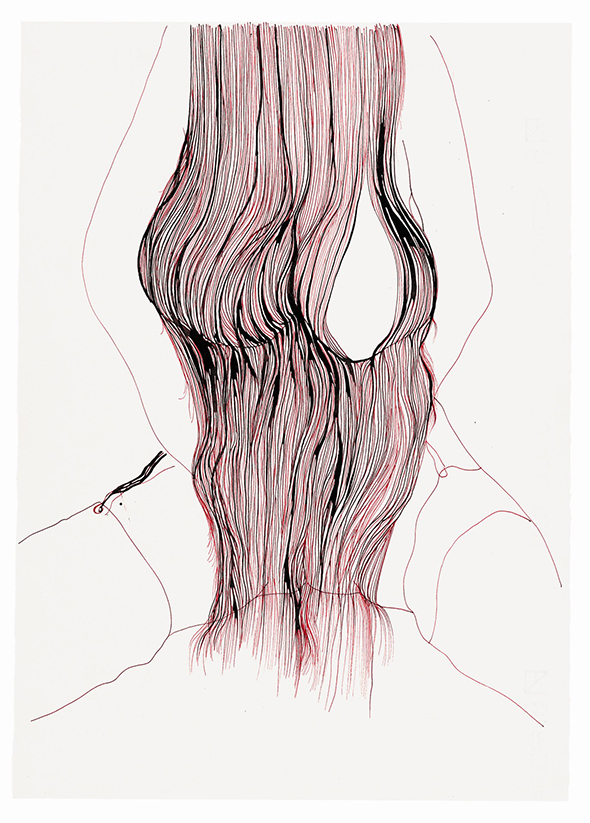

“Salomé” (1991), watercolour on paper

“Salomé” (1991), watercolour on paper

Similarly, your work immediately conjures up existential human tensions (life-death, permanence-temporality, strength-fragility). Is there a key dichotomy that you try to explore in all of your works?

My work is a mental theatre that refers to secrets, projects, an autobiographical reading of life, but without any personal notion of “biography.” Words that come to mind are, viscerally baroque, a collage of human documents.

I like tough-mindedness, making anxiety visible, but simultaneously under control. I am interested in the dark nature of man. As Samuel Beckett did in his theater pieces, I focus on isolating characters in a specific time and space, in which they torture themselves and others with questions that have no answer. Especially the black figures in my oeuvre are recalling these tense emotions of isolation, fear, anxiety or even the uncanny part of love and sexuality. They are strange and scary, but at the same time seductive and magnetizing.

Art brings to light things that normally don’t belong to our consciousness. I ask a lot from the viewer. At moments one is completely confronted and in other works one receives sweet caresses. I hope to make work that is a turbine, generating intensity. In the end, the viewers, each with their own story, become part of the script, while my role is probably a role of guide to the interior world of “Hades”. If you like, you could define me as a manipulator of the viewer deepest fears, obsessions and desires. I don’t love art theory but i am strongly involved with ” la condition humaine’ or you could even say our human limitations and restrictions. As I already stated, I am in no way dogmatic with regard to life and art. I prefer doubt: the fundamental doubt with which philosophers seek to cull meaning from the world.

An artist can only stir and disturb the dark pool of the other.

“Untitled” (2004), oil stick on paper

“Untitled” (2004), oil stick on paper

Your exhibited work has been a balance between drawing and sculpture. I would love to hear more about your creative process, especially considering your movement between these two mediums. As a viewer, there is definitely an experiential difference reading your drawings as opposed to your sculptures. Are you exploring different elemental questions within each medium?

On January 2, 2001, I started the Baudelaire Project. It consists of a diary, a visual alphabet of ever changing moods. The means were drawing, pure and simple. It took me fifteen years to accept the protocol of a drawing: too close and personal. Probably this resentment towards personalized art came from my neo-conceptual upbringing. During my first years as an artist, I only wanted to create strange installation and objects (for example, my use of mirrors) without any link to the artist, hand or soul. After a highly productive decade, I lost the pleasure of making art. The creative process became to formal, a boring “protocol de travail” –

too much of an ordinary job, There was also a hidden danger in working only on ideas. My oeuvre could become sterile and dead. I did not wanted to become a post-modernist monkey. Drawing was and is a good solution to give yourself, as an artist, back the pleasure of total self expression and creation. My art got back its soul by confronting my sculptures with works on paper. As I was injecting blood in a dead corpse, miraculously bringing black puppets to life.

“Untitled” (1997), plaster, wax, lead, iron

“Untitled” (1997), plaster, wax, lead, iron

Your pieces that focus more on the human body, its fragments and remains, read more allegorical than anatomical. Are there particular objects, even parts of the body, that you gravitate towards using? Is there a captivating narrative in, say, hair?

It took me, as a neo-conceptual artist some time to overcome that allergy towards the use of the human body. Like Dr. Frankenstein and his assistant digging night after night in graveyards in order to collect body parts, I started with the cast of hands, the legs of a ballerina, a scull, and finally a female figure cast from flesh and bone. She was dressed up in black velvet, with long black hair covering her face, one that was anonymous and silent, the embodiment of a black spot. By using body parts, I returned back to the artist’s classical studio , introducing the Model and Artist relationship.

As in the Gothic novel, I am creating a virtual space, escaping the “real world”, where limits are imposed by culture and consciousness. My characters, as I mentioned before (theatre of Beckett) are set in circumstances arousing particular responses.

Paradoxically, as I have frequently experienced with admirers of my work, they generate a pleasurable fear. My black ladies are extraordinarily amenable to psychoanalytic interpretation. As one psychoanalyst once mentioned: my early black mirrors became black demons.

The experience of fear in art may exorcise fear, since artistic fear is chosen and controllable. Black hair is always masking the faces of the black ladies, completely concealing individual expression. They become completely unidentified while suggesting an unanimously shared experience: at the same time this physical uniformity reinforces and intensifies their enigmatic and symbolic nature. My black figures are recalling the link between “Death and Woman”, as well as the Symbolists’ interest in decadence and the erotic. Eros and Thanatos stand side by side invoking a world of fantasy, unconsciousness and dream-like ambiguity. As an example I want to mention one of the E. Munch paintings in which a woman strangles a man with her long black hair. Again, food for psychoanalysts’.

“The Knife” (2004), furcoat, knife, hair, puppet, life size

“The Knife” (2004), furcoat, knife, hair, puppet, life size

Memento mori references a collective body of artwork dating back to antiquity that engages the mortality of humanity. One may simply categorize your work into this larger theme, but you have curiously stated that you use the concept of the end of life to “overcome the condition of being mortal.” How does your work do that? Are you interested in reversing the traditional memento mori reading?

The concept of the “momento mori” in my oeuvre is in fact the theatrical scenes or darstellungen of symbols as in a dream. Of course, you could notice a cultural historical reference towards 17th century naturemorte, or vanitas vanitum et omnia vanitas, but my aim is to create another kind of complexity: a dreamlike mise en scene, familiar to the stories of Edgar Allen Poe: constructing a story, in the best gothic tradition. As Freud articulated: the self is a structure, like a house, haunted by history, this psychic “house” has many chambers that need to be opened if the house is to be livable. When the story has been told, secret rooms have been opened: eemember William Blake’s “Doors of Perception”.

Perhaps your best known pieces, such as “Salome” (1990) and “Black Widow” (1994), are direct and full-scale appropriations of the human body. Is there a confrontation that you’re looking to stage between your art and the audience?

We are talking about the 19th century “Salomé”, the Salomé Oscar Wilde has described so beautiful. A lot of my works are dealing with that well-known fin-de-siècle symptom, the Baudelairean aim of searching for the perfect Beauty and the knowledge of the impossibility to succeed. This creates often a special sentiment, called melancholy. Salomé does not succeed in her queeste (search) to seduce J. the Baptist. La femme fatale, “Salomé”, is a work in massive silver. Silver as a decadent ersatz mirror; surface and symbol; in the interpretation of Pausanias of Narcissus story. Narcissus had a twin sister who died very young. Each time, by looking in the water, he sees the face of his dead sister, finding comfort in melancholy. Absence of his beloved dead sister, or the absence of the self.

The “Black Widow” subverts the surface of things. As in J.L. Borges’ “The Ink Mirror,” Yakoeb sees his own reflection in the black ink mirror. Very often I obtain a melancholic identification of the audience with these black women: an unheimliche reversibility between, a black hole, a black spot, a thing and a woman.

Jan Van Oost – “Vanitas” (1997)

Jan Van Oost – “Vanitas” (1997)

You’ve pointed to the work of Wiertz, Spilliaert and Ensor as the major influences on your particular artistic language. All of them are quintessential representatives of the mid-late 19th century symbolists. How do you negotiate that kind of creative expression with a 21st century lifestyle and way of thinking, not to mention the 150 years of creative evolution since then?

One can not escape cultural heritage, but basically, although I am often classified as a kind of neo-symbolist, with strong Flemish Symbolist references, I feel more connected with artists such as P.P. Pasolini, J. Pollock or Francis Bacon. I like the radical nature in Pasolini, the intensity of Pollock’s gestures and actions, the decay and deconstruction of the corpses in Bacon paintings.

I guess good artists have a conflicted relationship with the real world. The only possible place for art and artists is at the margins of society by which a necessary tension is generated. I do not negotiate with the world. No compromise.

An artist is not a diplomat: he is a cowboy, taming wild horses, risking his neck. You can not tame a wild mustang by being sweet and gentle. Also, you may not ask an artist that he cuts off his own ear every day; but he may be brutal and radical and sensitive the same time.

As a follow-up, it could be said that your work is a defiant redactor of the virtuality of contemporary art. How do you position yourself relative to digital and new media art that is currently redefining the art world?

I am in no way into digital and new media art. My aim is to create silent & timeless art. Strange images, recalling strong emotions. Sentiments from the gutter, seduction by beauty, horror by fear. A perfect paradox. Charles Baudelaire said it well: “The first thing you need to get into art, is the capacity to get lost.”

Jan Van Oost – “Untitled from the Baudelaire Cycle” (2001), watercolor on paper

Jan Van Oost – “Untitled from the Baudelaire Cycle” (2001), watercolor on paper

How do you see the role of art and the artist as we move further into the 21st century? What fundamental artistic issues do you view as crucial when moving forward?

Art is forever a social function but an artist is not a sociologist. I do not believe in progress in art, since art is a mirror of society. The deepest fears of man are the same as thousand years ago. Of course there is something you could describe as the spirit of the moment, but concerning my own aim: being megalomaniacal enough to create a masterwork , which can compete with Caravaggio’s and other masterpieces of 400 years ago.

___________________________________________________________________________________

Additional Information

GALERIE ROLANDO ANSELMI

“The Demon Love” – JAN VAN OOST

Exhibition: Dec. 15, 2012 – Mar. 02, 2013

Opening Recption: Saturday, Dec. 15; 6pm

Erkelenzdamm 11 (click here for map)

___________________________________________________________________________________

Elizabeth Feder is a designer and writer from New York City currently based in San Francisco. She received her Bachelor of Architecture from The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art and is developing new work at the intersection of architecture, design, and digital space.