by Alison Hugill, studio photos by Alison Hugill // June 25, 2013

A survey of Mario de Vega’s artistic oeuvre – his impressive collection of site-specific interventions and acoustic events – leaves wide open the question of what goes on in his studio. Known for his electronic improvisation, experimental style and use of large-scale pyrotechnics, it is difficult to imagine the space that would contain these sights and sounds. Visiting de Vega’s Berlin-Friedrichshain studio, I was offered a glimpse of the artist’s method for executing his unconventional works.

The studio space is already identifiable as de Vega’s from the sidewalk, where his 2011 installation piece Tiere – a deer used for target practice, shot through with multi-colored arrows – stands visible to passersby. The Mexico City-born artist moved to Berlin three years ago and has been working between the two cities ever since. De Vega studied Sound and Stage Design for theatre in Mexico City and Sound Studies at the Universität der Künste in Berlin. Despite this emphasis, he works in a variety of media, including site-specific interventions, performance, design, video, sculpture and photography. As a sound artist, de Vega is concerned with confronting the limits of aural perception and his works often act as translations of high and low frequencies into audible sounds. His studio is a space for experimentation and research, the laboratory of someone engrossed in the study of sound as both a sensory and perceptual event. With this acoustic fascination at their core, the projects that emerge assume a myriad of material forms.

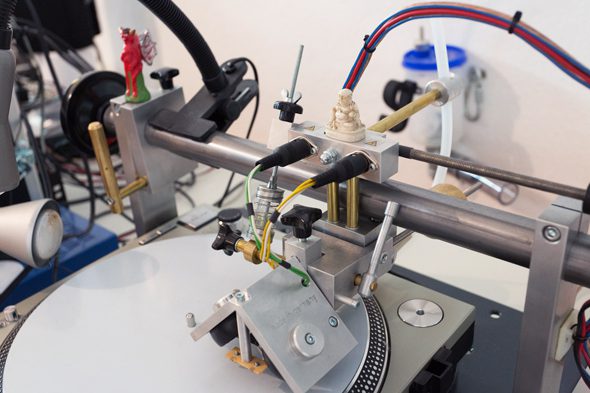

On the tables in the first room of Mario de Vega’s studio lie numerous soundboards, antennae and small circuit boards used for designing electronic equipment, as well as a vinyl-pressing machine. It is here that de Vega works out his projects for the ‘materialization’ of electromagnetic activity. One of his recent series, Traffic, exemplifies this aspect of his artistic practice: de Vega has recorded frequencies from personal mobile devices in crowded places in New York City and amplified their sound to levels where it can be heard. He has then made vinyl recordings of these amplified frequencies, each record personalized with a postcard image of the mobile phone user in action. In this way, he has managed to produce a compact testament to this banal everyday experience, elevating it to the level of perceived phenomena and placing it in a context usually reserved for a musical composition.

De Vega’s two-room workspace is shared with a fellow sound artist and creative collaborator. Together they make up ://R, a platform researching topics related to “irritation, data corruption, propaganda, design, hidden signals amplification and psychoacoustics.” Through a series of projects, publications and workshops, ://R has shed light on a fascinating aspect of sound studies. Much of their work focuses on the possibility of making the unheard heard, of amplifying those background noises that are ubiquitous but go unnoticed in our daily lives.

Infrasound is of particular interest to the artist, as the frequencies lower than the normal limit of human hearing often have the ability to produce a visceral reaction in the listener. Experiments in psychoacoustics –the study of psychological and physiological responses to sound–register the bodily modifications resulting from sound perception. The subjective results, immeasurable except through interpersonal description and shared reaction, are the crux of de Vega’s research. Through his work with frequency and resonance, he is interested in exposing human vulnerability and perceptual awareness.

Launching into a discussion of his more ‘explosive’ works, I learn that de Vega prefers to undertake these experiments in Mexico, where he has contact with a family-run pyrotechnic distributor on the outskirts of the city. The works he creates in various gallery spaces in the country, in which he detonates large quantities of gunpowder and other explosive materials, are collaborative works. He admits they are not rehearsed and rely on the experienced opinion of a few trusted individuals. De Vega remarks that these works are not easily done in Europe, where a mountain of paperwork and red tape slows down the process to a halt. In Mexico, he has been able to perform a number of audio-visual actions, including his 2008 electronic detonation of 3.5 kilograms of gunpowder, placed in 28 craft-board containers. These works are documented and recorded and later shown in the gallery context. When they are enacted, however, there is rarely an audience to witness them.

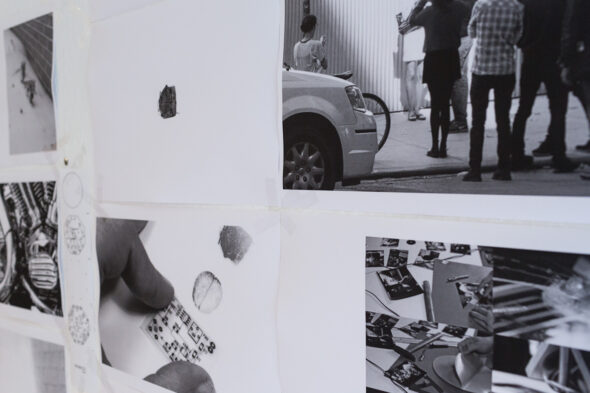

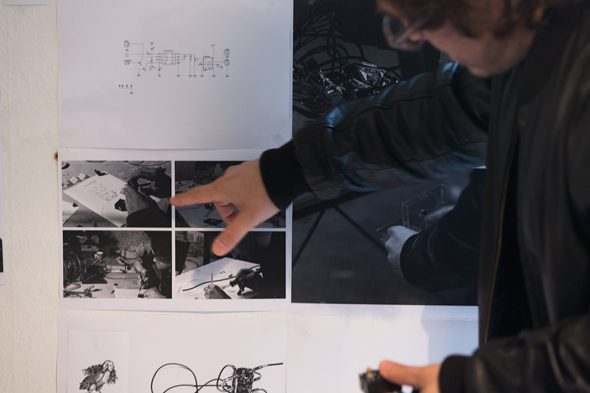

The tension between documentation and performance is ever-present in de Vega’s artistic practice. Most of his pieces are presented as documents of their execution, with few witnesses to their physical enactment. His studio work consists largely in finding formal solutions for the presentation of his work, which is often site-specific and temporary. Yet when he does sound performances in public, they have a decidedly theatrical flair. De Vega is aware of the value of being present in and through his work. Electronic music performance can sometimes be quite alienating, when the artist or musician involved merely presses play on a laptop or hunches over their equipment, unenthused.

To delineate physically the artist’s twofold process within the studio itself, it would seem that the front entrance room represents the collaborative, experimental, more expressive workspace, while the back room represents the detailed, considered act of solidifying and representing these creative flows. Whether in the initial stages of planning a work, or in the editing and documenting phase, it is clear that de Vega has a vision. But this vision, it would seem, is always bound up in the process itself and often yields unpredictable results. The impetus behind his works is the study of the acoustic in all its aspects. Each of de Vega’s performances, installations or interventions seems to unearth a fascinating and untapped feature of our daily soundscape.

Artist Info

Writer Info

Alison Hugillhas a Masters degree in Art Theory from Goldsmiths College, University of London. Alison is the Arts & Culture Editor of Review 31 and is based in Berlin. review31.co.uk