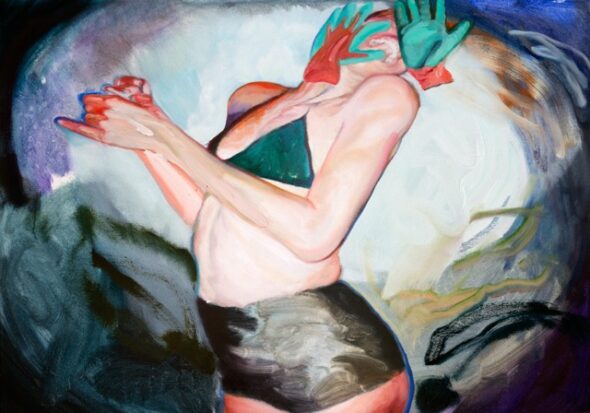

“Power Play in Another’s Backyard”, oil on canvas, 110 x 160cm; Photo courtesy of the artist

“Power Play in Another’s Backyard”, oil on canvas, 110 x 160cm; Photo courtesy of the artist

Article and photos by Florence Reidenbach in Berlin; Monday, November 4, 2013.

In Winston Chmielinski’s first solo exhibition in Berlin, Laughter, the artist concentrates on figures that he intermingles with abstraction, defining a zone where the two don’t simply coexist but rather constitute a new exploratory space. He uses the traditional medium of painting for his art. However, the technique of this child of the 90’s is saturated by new media. The painter is a gamer. The painter is a self-taught artist who has grown up with the Internet, playing Everquest.

In a post-Sensation (exhibition) era, Chmielinski presents the human figure in a very visceral way, using flamboyant and flashy colours, that have the peculiar glow of the digital world. He creates an imagery of his own, an imagery so colourful that it becomes a trademark.

“Low to the Ground”, oil on canvas, 40 x 60cm

“Low to the Ground”, oil on canvas, 40 x 60cm

Chmielinski’s art is indeed visceral. It is sensuous and its strokes are generous, making the paintings as luxuriant as Monet’s natural scenes or as lyrical as Matisse’s. There is something exhilarating about them as they suggest extreme feelings and reactions to the viewer. There is also something chaotic about the compositions from which the human figure emerges. They can evoke birth as well as death: it is not clear whether they represent people alive or corpses, yet they have everything to do with the materiality of being alive. It is similar to the “viscerality” you find in Bacon’s paintings: Chmielinski’s work captures it and immerses us in it.

The flesh depicted is palpable and tangible, and if it can evoke the carnality of Jenny Saville, Freud, Schiele or Rubens’ bodies, to name a few, there is something else about them that we don’t normally find in painting. It is something we find in the moving image. Something is swarming. Matter is swarming the same way the cursed boar’s flesh is in Hayao Miyazaki’s Princess Mononoke. What is fascinating about it all, is that we are facing a still image: a painted canvas.

“Three Can Be So Vicious”, oil on canvas, 50 x 70cm

“Three Can Be So Vicious”, oil on canvas, 50 x 70cm

The amount of references is vast in Chmielinski’s work. Rare are artworks that can travel this far back in history, and concentrate that many references, connecting with the works of different artists of various times, and still be this unique.

If painting is a traditional medium, what is unconventional about Chmielinski’s work goes far beyond what seems to be at first an association of figuration, photorealism and abstraction. Not much paint is applied on the canvas: it is all about the colours and the shapes defined by those uncanny strokes. It is about the intensity of shapes and colours appearing on the canvas. On a screen, a digital image has no physical texture: its pixels and colours suggest infinite possibilities. The various zones of colours make one’s eyes wander in Chmielinski’s paintings. What is captured is not fixed in lines because each stroke defines multiple possibilities of movement.

The represented bodies seem to float as if we could navigate around them and examine them from various angles. The gamer in me is reminded of the first person-view you get in many video games. The first person view existed in some shooter games in the 90s, but it was a whole new experience once it was introduced in persistent universes of role-playing games like Everquest. That view immerses the player into the fantasy world.

Looking at Chmielinski’s paintings, the viewer feels less like a third-party. Painting, created in its traditional practice, can be enriched by what the digital era has to offer, and what’s more, it can be activated by digital interactivity. The abstract zone actually evokes the camera moving around an image to reveal all its angles like in a game.

“Trigger”, oil on canvas, 70 x 100cm

“Trigger”, oil on canvas, 70 x 100cm

The artist works on an impulse and this is what triggers the painting. Trigger, which is a clear gaming term, is even the title of a painting in the show. When explaining how he would just seize a situation, a feeling, etc. and take hold of it in the painting, his gesture was reminiscent of someone grabbing a glass to capture a bee under it. So the gamer-painter is on a mission. It is not so much about transposing. Rather, he has to deliberately report and give an account of what made him react. He uses snapshots from his smartphone as a starting point. Something realistic that triggers that impulse he translates into a sensational chaos, where the human figure finds its place.

Winston Chmielinski is showing us what the perspective of the digital world can bring to painting. He reminds us that the possibilities of strokes are infinite, and that painting is always evolving.

___________________________________________________________________________________