Article by Xandra Popescu in Berlin; Thursday, Nov. 7, 2013

The Berlin Farm Lab; photos courtesy of Valentina Karga

The Berlin Farm Lab; photos courtesy of Valentina Karga

Berlin´s job market can be a site of extraordinary speculative pessimism. Flooded with overqualified transitory workers, the job market is a perpetual source of hopelessness and exploitation. Anxiety proliferates among the young and the able. But at the same time, we are witnessing an increased preoccupation with self-sufficiency and autonomous life tactics. In this respect, the work of Greek artist Valentina Karga was a very exciting discovery. I went to see her at Effizienzhaus in Berlin, where she was speaking about her artistic research, the Berlin Farm Lab.

Effizienzhaus, the place of our encounter, is itself laden with connotations. Built as an initiative of the Federal Ministry of Transport, Building and Urban Development (BMVBS), the Effizienzhaus is a prototype house which is able to produce more energy than it actually consumes. This living space now serves for demonstration purposes but also functions as a venue for different ecology-related events. Karga´s project Berlin Farm Lab is a site for experimentation on sustainability and self-sufficiency techniques.

Amidst all the high end technologies of the Effizienzhaus, Karga prompted the audience to consider low-tech solutions and grassroots technologies. She believes that architecture´s mission must change to accommodate new alternative lifestyles. During the presentation I learned that the Berlin Farm Lab was hosting a Summer School for Applied Autonomy. On a rotational basis, two participants at a time could experience an autonomous lifestyle for a period of one to two weeks. At the end of their stay they would overlap with the next group to pass on their know-how on maintaining the system.

Karga´s proposal sounded courageous and intriguing so I decided to pay her a visit in the next week. The Farm Lab is situated in Marzahn, an area of Berlin which was once a site for massive urban development projects in the GDR. The place is not exactly idyllic, but it certainly has its own charm. The Lab spreads out on a concrete platform, so farming is realized on raised-beds. Unlike the Effizienzhaus, the Farm Lab has something frugal and improvised about it, like a summer kitchen in the countryside. A triangular shelter, a wooden table, along with several seemingly haphazard elements such as three bathtubs, what seems to be a barrel shower and two armchairs built out of flat tires…“these are the lazy chairs,” Karga explained.

The Berlin Farm Lab – Water Purification System; photos courtesy of Valentina Karga

The Berlin Farm Lab – Water Purification System; photos courtesy of Valentina Karga

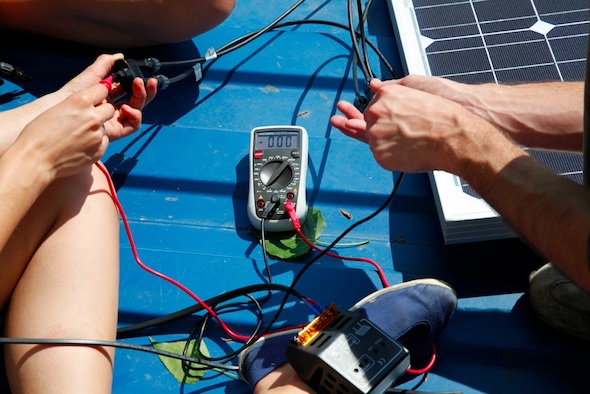

Karga gave me a tour of the place and I found that many of the “misplaced elements” were in fact ingenious utilities systems. What looked like an improvised shower was actually an automated irrigation system. For electric energy they use photovoltaics on the rooftop which deliver just enough to power one laptop and a lamp in the evening. “We should have built a windmill to take advantage of Berlin´s windy weather, but at the time I didn’t think it was something we’d be able to pull off,” said Karga.

There were three cooking devices: a rocket stove, a gasifier and a solar cooker. “How does this work, is it more like baking or boiling?” I inquired. “It´s more like a slow cooker – it preserves a lot of the vegetables´ taste” she explained. “And what are these?” I asked, pointing at two canned buckets on the ground. “Oh, I think those are Robert´s and Conrad´s feces”. Robert and Conrad, were the last two residents and their feces had been destined for the compost system. Then, she introduced me to the compost toilet. Situated behind the wooden shelter, the toilet presented itself as a double seated system which separates the feces from the urine. For those who might be put off by this method, it is worth considering that in Japan this system, complemented by good design, is already used on a large scale. Apparently this procedure prevents the formation of odour. Karga told me that compost toilets are the toilets of the future, they save clean water and generate a valuable and otherwise expensive fertilizer.

What is fascinating is that all the living utilities of the Lab are connected into a close loop system in which there is no waste – just renewed resources. “The participants not only maintain the farm, but the system´s streams pass through their own bodies” she explains. When the tour was over we sat down on the ‘lazy chairs’ and I started prying a bit. I wondered if, like me, she was brought up in a housing block. But no, she grew up in a house in a rural area. She comes from a small town in Greece and her father is a mechanical engineer so she grew up just above a garage. “Maybe that is why you are so crafty,” I speculated. “I don’t know if I’m that crafty, but yes, I like crafting. It´s a very meditational thing because it produces a state of awareness where you are involved in something tactile and yet detached enough to react to what´s going on.”

The Berlin Farm Lab – Photovoltaics; photos courtesy of Valentina Karga

The Berlin Farm Lab – Photovoltaics; photos courtesy of Valentina Karga

I was eager to understand how she devised all of the gadgets that surrounded us. Karga´s explorations go way back. For her graduation thesis she created the Greenwashing manual and the Green Washer sustainable active chamber – in her own words “a series of systems aimed at an ecologically bearable, conscious, contemporary lifestyle.” The Berlin Farm Lab is a continuation of that project. In spite of her extensive research and know-how, Karga likes to call herself an amateur. “I hope I will always remain an amateur” she avowed with a dreamy expression. She is proud to acknowledge that many of her explorations were carried out through internet research: Youtube do-it-yourself videos and forums. “Many of these utilities were devised through trial and error. At first most of them didn’t work.”

We spoke about the social dimension of this experience. In her research Karga deals with the idea of self-sufficiency in the era of the new commons: collaboration, communication and knowledge. One of her research aims is the circuit of knowledge: “the way online culture is effecting the offline and how metropolitan and provincial lifestyles intertwine.” So the Farm Lab is not only about self-sufficiency but also a site for experimentation in the fields of social knowledge production, collaboration and cohabitation tactics. In order for things to work, participants must dedicate time to maintaining the system in consideration of future residents. During their stay they are asked to document their experience through a free format diary or recording. At the end of their stay they pass on their acquired knowledge of composting, feeding the biogas digester, adjusting the solar panels towards the sun, checking solar energy levels, repairing things, maintaining the aquaponic system or filling in the arduino water barrel.

During our discussion, I brought up the phenomenon of communes or autonomous zones that were popularized in the 60´s. Many of these experiments ended up in defeat, often emulating the same hegemonic mechanism of the society they had separated from. Karga, on the other hand, seems surprisingly undogmatic for somebody who has devised such an autonomous system. “There are two ways to do this,” she explains. “You either become a hermit or you build a community. But what happened with many of these projects is that they became hegemonic. That usually happens when members are too attached to their ideas. And then new hierarchies emerge. Or people usually join such communities to escape dependence and suppression. So when hierarchies emerge, participants become polemic, because they joined the communes in order to be free.”

The Berlin Farm Lab – Participants; photos courtesy of Valentina Karga

The Berlin Farm Lab – Participants; photos courtesy of Valentina Karga

What sets the Berlin Farm Lab apart from other such initiatives is the fact that it was conceived as a permeable system. “This is not a project for people to stay here. It is designed to give you a taste of self-sufficiency. But many of the people who go through this are left wanting more. Here you learn how to fulfill your basic needs and this makes you free from suppression. Of course this may be dreary and uncomfortable. But our comfortable lives come at the price of our own suppression. We all have to play by the rules of a power game and subscribe to a certain hierarchy.”

Some people have asked me “How is this art?” “How is this not art?” I could retort. Instead I confronted Karga with this, after all legitimate questions had been asked. She laughed and told me that coming from architecture she had often been asked how her work is architecture. “I think it is the market which defines what art is. If it is not marketable it is not art. But I will not hide from this question. This is art because it reflects on a deep social need and it asks questions. Why are people nowadays so interested in surviving by their own means? What motivates this resurgence of interest for autonomy and self-sufficiency? Why do we want to grow our own food and have photovoltaics. Why bother? Youtube is flooded with DIY videos. I think there is a deeply engrained social need for autonomy. People feel the need to know they can be self-reliant. This is art but it is also science, education and economy.”

Trying to play the devil´s advocate, I pointed out that this kind of lifestyle is hardly for everybody: ”are you suggesting that we should all quit our jobs and become self-sufficient?”

“Not at all,” she responded. “But having the know-how to be self-reliant gives you the confidence to know that you can always quit. And with that confidence comes a new attitude towards work and the power relations around us. This kind of experience can potentially set us free from our fears.”

If she is right then the idea of temporary or periodic withdrawals might be one of the most powerful political instruments at our disposal.

The Berlin Farm Lab – Garden; photos courtesy of Valentina Karga

The Berlin Farm Lab – Garden; photos courtesy of Valentina Karga

___________________________________________________________________________________

For additional information check out the BERLIN FARM LAB website

___________________________________________________________________________________

Xandra Popescu works as a writer and filmmaker. She holds an MA in Dramatic Writing from the National Theater and Film University in Bucharest and has a background in Political Science. Since 2011, together with Larisa Crunteanu and Alice Gancevici, she runs a project space in Bucharest called Atelier 35.