Article by Linus Ignatius in Berlin; Friday, May 23, 2014

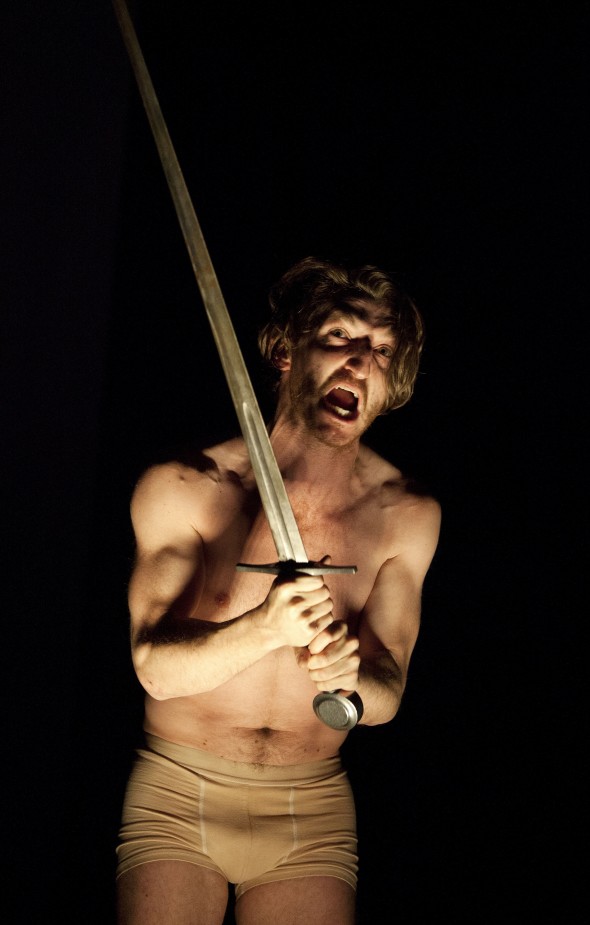

Actor Christopher Nell; Photograph by Lucie Jansch

Actor Christopher Nell; Photograph by Lucie Jansch

Hamlet. The ultimate hipster. Denmark’s high society may scoff at his enigmatic antics but we understand his plight. He is so cool.

I wince as he slashes open Polonius’ corpse, tearing out the entrails therein (purplish and noodle-like). He digs out a beating heart, and then a big grey brain. It occurs to me as he monologues wildly – his clothes soaked with blood – that perhaps he is not such a champ after all.

Suddenly a cheesy show tune blasts from the rafters. The lights turn a sickly purple-green. Hamlet raises his sword like a baton and the corpse hops up, grinning. The set – a misty labyrinth of blackened wall fragments – groans as it begins to rotate. Deep within the darkness silhouettes lurk mysteriously, only visible for a moment as the set creaks and turns, while, like marionettes, the killer and his victim begin to dance.

I am watching Leander Haußmann’s subversive take on Hamlet this season at the Berliner Ensemble. Featuring resident Christopher Nell in the title role, Haußmann’s bizarre production incorporates a hodge-podge of slapstick bits (think Looney Tunes meets commedia dell’arte), original folk entr’actes (performed live by a duo of androgynous angels**), and occasional spurts of nerve-jolting gunfire. The feeling is modern – with one physical gag even throwing a nod to the bouncers at Berghain – and the effect is overwhelming, building a deep-seated uneasiness in the theatergoer that lingers far after the close of this carnivalesque, four-hour nightmare.

Nell himself is the master of ceremonies, taking on the corruption of Hamlet’s spirit with a virtuosic charm that slowly gives way to full-blown hysterics. By the end of Act I he kneels at the lip of the stage drenched in Tarantino crimson, panting wildly like a beast with his blue eyes transfixed over the audience. Shreds of paper blow all over the stage: Ophelia’s torn-up love letters. Thunder crashes. The curtain falls. It’s safe to say: I’ve never seen a Hamlet like this.

***

This astonishing piece is part of a larger effort on the part of the theater to revitalize not only Shakespeare’s classic works but also the theories and practices at the very foundation of the Ensemble itself.

Formed by Bertolt Brecht in the years after the war, the Berliner Ensemble represents an essential space for post-war political activism in the arts. After living in exile under the Nazi regime, Brecht returned to Berlin with a determination to use art in the essential struggle against tragic, resistible evils, like those that had recently taken hold of Germany. To do so he pioneered a technique called “Epic Theater” – a politicized approach to staging that aimed to engage the intellect, not just the emotions – in the hopes that he might help train a generation of free-thinking theatergoers.

For him, ‘catharsis’ in art was like propaganda, sedating the masses and perpetuating an oppressive dominant society. Making use of a puppet-like acting technique called Gestus – in which the actors’ movement and speech is intentionally disjointed from their naturalistic behavior – Brechtian productions keep the audience at a distance from the imagined reality of the play, instead asking that they really consider the socio-political problems portrayed on stage. He dubbed this the Verfremdungseffekt.

Haußmann’s “Hamlet” is scrupulously attentive to this idea – bombarding the viewer with the extremes of Shakespeare’s drama but never offering a semblance emotional resolution. Hauntingly, this remains true down to the final moments of the play.

Typically, the play ends with Hamlet’s dramatic martyrdom. “Tell my story,” he begs of his friend Horatio, before falling in the spotlight: a true tragic hero. In this production, though, he is robbed of his apotheosis. As a spastic, acrobatic sword fight rages over a banquet table center stage, with the set revolving at a full tilt, numerous spirit-like figures begin to emerge out of the wings and steal focus, led by the two angels and chanting the refrain of an old Bob Dylan song: “just remember that death is not the end.”

And then a score of backstage workers pours onstage, clad in black and equipped with headsets and battery packs. Murmuring and diligent, the stagehands lift and adjust the wall segments carefully, slowly obscuring the heavenly portrait of Hamlet’s final battle. Until, before you know it, the show is over.

This anti-climax reminds me of the tendency to omit or downplay the narrative of Hitler’s death in German textbooks and memorials. A mere parking lot covers Hitler’s final resting spot, unremarkable and non-commemorative. It marks a choice to move on humbly, to remember our true heroes, and to scrutinize our villains’ mistakes. This is the lesson learned from Haußmann’s genius rendition of Hamlet: that even a hero can have a monster within.

*the eerie, post-apocalyptic work of designer Johannes Schütz

**(played by Norwegian duo Apples in Space)

___________________________________________________________________________________

Additional Information

BERLINER ENSEMBLE

Theater am Schiffbauerdamm

Bertolt-Brecht-Platz 1 (click here for map)

___________________________________________________________________________________

Linus Ignatius is a director and actor hailing from Brooklyn, NY. He studied theater and cinema at Oberlin College before spending time at a film school in the Czech Republic and finally moving to Berlin. He recently completed an immersive theater piece called HOUSE — staged in a prairie home in Ohio designed by Frank Lloyd Wright — as well as a number of smaller film projects. He is currently putting together an alternative production company called the god complex