by AJ Kiyoizumi, studio photos by Claudio D’Alò // July 21, 2014

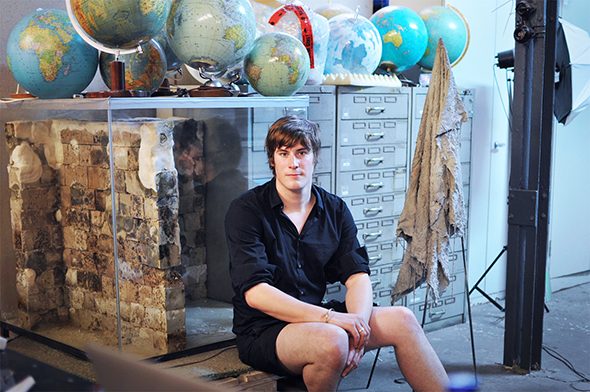

Julian Charrière has his own desk in the massive yet packed studio space he shares with his friends and former classmates, on which sits a jar of radioactive soil from Kazakhstan. His work area is also surrounded by almost a dozen globes, some with territories sanded down from his work called “We are all astronauts aboard a little spaceship called earth” (2013). These globes rest on top of a glass case with fungus and mold growing on brick, from “And Some Other Obscure Traces Of” (2011-2013). As he holds up the radiation sensor to the dirt in the clear jar, amid the beeps he laughs and assures us it’s not so dangerous now that it’s sealed. But “if you breathe it in, it will be in your body forever,” he says.

He adopts a more serious tone and explains that the mold and fungi in the adjacent vitrines are similarly dangerous, as after working with them for a large exhibition, he became ill. Charrière could easily have a TV show or movie made about him. He just got back from Kazakhstan, about to head to India to check out the stomping grounds of Kochi Muziris Biennale, then after that to Milan to work on his artist book with Mousse publishing house, and then to Chile.

He was recently commissioned, along with peer and friend Julius von Bismarck (they were both students together in Olafur Eliasson’s Institut für Raumexperimente at the Berlin University of the Arts), to create an artwork for famed collector Francesca von Habsburg’s Treasure of Lima: A Buried Exhibition. The mission was to take works of art and bury them at the island, known for its alleged buried treasure worth around $300 million. The piece he worked on was buried on the island and a code leading to its location will be sold at an auction to benefit conservation and marine protection for the island, including its exceptionally high shark population.

Charrière’s projects and art are fascinating in both concept and aesthetic. Another previous project with von Bismarck landed his name on headlines, when they designed a contraption for the piece “Some Pigeons Are More Equal Than Others” (2012, as part of the Venice Architecture Biennial) to capture and dye pigeons with tropical hues and release them back into the skies, to fly next to their drab counterparts. His work demonstrates this interest in public space and perception, bringing in elements of ephemerality, as seen with his references to land art.

His site-specific work “The Blue Fossil Entropic Stories” (2012) involved the artist trudging around on a glacier in Iceland with a blowtorch, attempting to melt the ice over eight hours. “90 percent of people think it is Photoshop,” he says. “Or with the painted pigeons, until someone sees that it’s real, people never know if I am betraying them or not.” Revealing an unexpected yet bold point of view is one of Charrière’s greatest strengths, and the methods of doing so often involve a spirit of “romanticism and the great discoveries, like Alexander von Humboldt. You never know what he brings back, whether it’s science or fiction. You never know what is truth and what is not.”

Like von Humboldt, Charrière brings together a curiosity about earth sciences, the diversity of the physical and natural world, and a passion for traveling. Charrière refuses to describe his solo works, in comparison to his works with the other members of the artist collective he belongs to, Das Numen, as scientific or technical, saying: “I use some scientific methods, but I would describe it more as an archeologist or geologist. I go into the field and get inspired by what I see, then I bring things back to the studio and do work.”

Because much of his work is so site-specific, it would seem frustrating for an artist to only be able to present documentation of his work in a white cube setting. But for Charrière, he almost likes it better that way. He is a messenger, bringing back the essence of the place where he has been. And it’s not just documentation, either, but a layered representation of the experiences of the specific place. For example, his recent experiments include a roll of film he had shot at a nuclear test site in Kazakhstan. Instead of simply exhibiting the photos he took there, he is currently working on a project that reflects the region’s historical and mythical complexities. He sprinkles the radioactive dust onto the undeveloped negatives to eat away at the film, then develops them a second time. The result creates a variety of effects such as ghost-like clouds and thin scratches throughout the frames.

In the case of his recent travels to Kazakhstan, he knew what he wanted to do going into the trip, which was mainly to create a film. The site he visited was a Soviet Union nuclear test site, what he calls a “monument of the nuclear age.” It’s also known as Semipalatinsk-21. Though testing ended in 1989 and the complex closed in 1991, the surrounding areas remain significantly irradiated. Charrière mentions that it will stay this way for thousands of years, so he “wanted to get to this space and make a recording to reflect how it could be in 500 years.” His descriptions of the sun-dial aesthetic of the on-site architecture and the charged elements there also relate to the term that Charrière has coined as his main interest: “future archeology.”

It partly comes from his curiosity through reading, his other main source of inspiration besides traveling. The science fiction stories of J. G. Ballard in particular inspire his nuclear site work and his newest interest in lithium production in relation to flows of cosmic and individual consciousness. Ballard’s short story The Voices of Time influenced Robert Smithson’s “Spiral Jetty,” as the story includes allusions to the nuclear test site Enewetak Atoll, a nuclear deposit site in the shape of a cratered mandala. In Charrière’s case, he was inspired to go to Kazakhstan by the short story The Terminal Beach, which features a man’s trance-like and futile wanderings on an island formerly used for nuclear testing. Questions of lucidity and extinction are at the forefront of the bleak story set in a landscape “covered by strange ciphers”: a similar description can be said of Charrière’s setting for his film and photographs from Semipalatinsk.

Charrière’s next move is the lithium triangle of Chile, Argentina, and Bolivia. He describes it in a metaphysical way, saying that our entire “expanded reality and western society are based on materials that are pretty earth-bound.” In the Stone Age, for example, he describes the progression of humankind from using stone as a weapon, then to build walls, then as a foundation for something like a temple to provide culture for a society. As we are transitioning into a new age out of the nuclear age, many might not know it, but lithium’s role is problem-ridden and gargantuan. “We forget that our laptop is coming from the earth — or I forget at least,” says Charrière. “If you don’t have a big hole in China, then you won’t get your iPhone. So I am interested in the big hole.” Instead of the physical temple as our monument of culture, he says, it’s now invisible and incarnate as the world wide web.

He plans to visit the sodium deposits at Salar Grande in Chile, hoping to witness these sites of manufacture and examine “the relations between our society and the way we are thinking.” Charrière’s way of thinking is in no way single-minded, as he continues to rise in popularity and his dimensionality of projects deepens. In June, he presented some of his recent work as a part of the Moscow Young Artists Biennale. He currently has artwork featured in an exhibition at 401 Contemporary here in Berlin, and is planning his first large solo museum show to open in Switzerland in October.