Article and photos by AJ Kiyoizumi in San Francisco; Tuesday, Sep. 30, 2014

Ai Weiwei doesn’t get to see his own exhibits in person anymore. With selective enforcement and dubious claims, his passport was taken after he was under house arrest for evading taxes in Beijing. He is unable to attend openings or accept prestigious professorships, as we saw with his show at the Martin-Gropius-Bau a few months ago.

He resorts to looking at photos of his exhibit presumably through Twitter and Instagram tags, of which there will be plenty for his new show in San Francisco titled, “@Large: Ai Weiwei on Alcatraz.” The site is a place so rich with conflict and human rights violations during its time used as a prison and fortress and now, perversely, is a spot for mass tourism. The show doesn’t cost extra for visitors that are already heading to the island, and it offers a chance to not only see some of Weiwei’s large-scale installations, but also to see parts of the prison complex not previously open to the public. Parts of the hospital, psychiatric ward, unrenovated A-cell blocks, and, most eerily, the New Industries building — where prisoners were “encouraged” to work, overseen by guards striding in the lofted gun gallery — house his work, despite the fact that many of the most compelling structures on the island are half-crumbled, now crawling with vegetation.

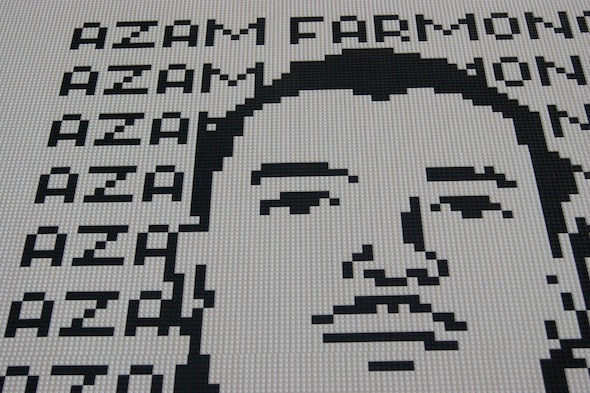

But the caging-in of his structures is thoughtful. We see motifs of flight with the large works “With Wind,” and “Refraction,” a dragon and wing structure, respectively. Placed indoors, we experience the dissonance between hope for freedom and physical limitations. Of the seven installations, “Refraction” is most mysterious, as only a fragmented view of it is accessible from the gun gallery through the fangs of broken glass. It’s also the least colorful or pristine of the pieces: despite the themes of dissident imprisonment, many pieces have cheery aesthetics. The primary colors of the 176 LEGO portraits of political exiles and prisoners, the rainbow hand-painted kites of “With Wind,” and the pristine, slick porcelain flowers of “Blossom” possess the look of souvenirs.

Weiwei seems to have tailored his work to the mass audiences who come to the island more for a peek at the psychopathic “Birdman of Alcatraz”’s hospital bed or the chill of maybe stepping onto the same ground on which the shackled Al Capone might have also shuffled. Weiwei’s works are not as personal as some of his last pieces, but instead put the attention on other and larger trends of injustice worldwide. The LEGO portraits of “Trace” symbolically unite figures on a single plane such as Martin Luther King, Jr., Chelsea Manning, and Shaker Aamer, a Saudi Londoner detained, tortured, and still held at Guantanamo Bay Prison despite being cleared for release more than six years ago.

Fat binders rest on lecterns at the end of the hall, with short stories of each of these figures. No one can possibly read all of the biographies in one visit, so they are also available online. In the resulting low-resolution depictions from the blocks, we are extraordinarily distanced from them. The visual is entertaining, but the project works better online, as one can research each of these humans and the controversy that surrounds their situations and fates.

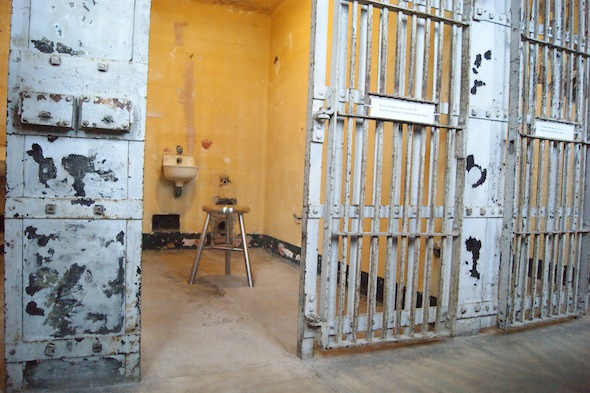

The installations on Alcatraz are easily digestible. We understand that we should be drawn in by the dramatic visuals, and the symbolism is for the most part an easy translation. In this way, Weiwei was smart to not alienate the crowds visiting Alcatraz, as they aren’t necessarily visiting solely for his art. But large crowds and boisterous tour guides make the reception of the pieces a bit difficult. This is especially true for the two sound installations, “Stay Tuned” and “Illumination.” The walls that kept prisoners secure also contain and reverberate noise. But what’s needed for “Stay Tuned” is solitude. A single metal stool (echoing the shape of the stools that covered the Martin-Gropius-Bau’s entry hallway) sits in each of the 12 cells, each cage filled with the sounds of literary or musical expressions by activists and prisoners. It’s a moving experience, but an interrupted one.

Perhaps the most compelling or, at least, curious, part of the exhibition is its inception. The For Site Foundation, with Cheryl Haines at the helm, has teamed up with one of the most famous contemporary artists today, the Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy, and the National Park Service at one of the busiest tourist attractions in California. In the remarks at the media preview, Haines made it sound as if she just pitched her idea to the artist and it all developed quickly from there. Though there’s no reason to be suspicious, the anecdote does seem incredulous. It is clear there are many influential donors and backers, and the project will undoubtedly bring incredible numbers to San Francisco and Alcatraz for the next seven months. It’s easy to envision the pieces becoming permanent installations on the island, adding to its heavy history.

___________________________________________________________________________________

Additional Information

Ai Weiwei on Alcatrez

Exhibition: Sep. 27, 2014 – Apr. 26, 2015

Alcatraz Island, San Francisco, USA

___________________________________________________________________________________