by Henry Andersen, studio photos by Conor Clarke // Nov. 5, 2014

Arriving at the Friedrichshain studio of Daniel Gustav Cramer, I did not bring any zoom recorder or other microphone, only a pencil and small writing pad. Cramer and I had spoken via email about not wanting the visit to feel too much like a formal interview. I had some vague notion that given his work (which deals extensively with concepts of memory and personal archiving), my handwritten notes and scribbled topics of conversation would somehow get closer to the heart of the matter than any microphone. Reading them back now, after an interval of several weeks, the notes make for a bizarre read: a disparate collection of names, book titles and hardly legible phrases. Taken in isolation, each note seems incidental or even banal. But taken as a collection, the quickly-jotted notes start to sketch out something of the disparate reference points that inform Cramer’s practice: “Bonnie ‘Prince’ Billy” I had written, “Perec – Life a User’s Manual”, “Hasselblad Camera”, “Morandi, Giorgio” and (cryptically) “until we had climbed Everest…”

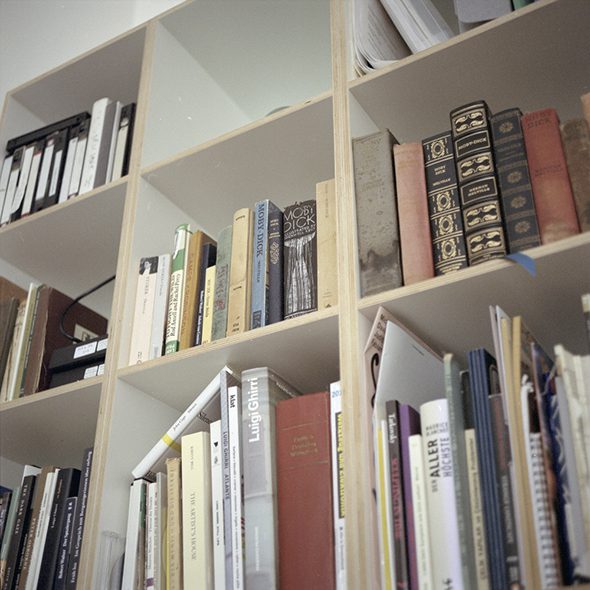

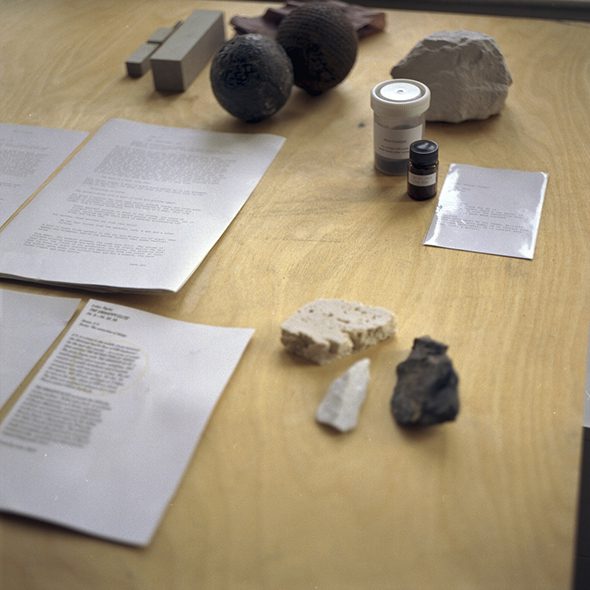

The studio itself is a large sunlit room with a view onto a park, the space broken up by three large desks: one for computer work, one with a photographic viewfinder and one by the window with a collection of texts and small objects. Cramer shares the apartment with his partner and sometimes collaborator Haris Epaminonda and the couple’s young son. In one corner of the studio is a series of small, white boxes which house a huge archive of photographs by himself and others. A particular favourite of mine is a collection of post cards from small cities that share names with larger ones; Perth in Scotland, Paris in Texas, etc. Cramer shows me a book he had bought which chronologically lists every reported ghost sighting in Scotland and Wales. We speak about Borges’ The Library of Babel and the feeling of security and knowledge accumulation that comes from archiving. Across from his archive, in the other corner of the room is a smooth, propellor-powered camera-drone that Cramer explains he plans maybe to one day use for a Vampire movie.

Cramer’s practice is quite varied, including photography, video, text and some objects. It is ‘conceptual,’ but only in a loose form of that word (more on this later). Cramer’s ongoing series Tales (begun in 2005) perhaps serves as a good point of access to his other work. Formally, the series is incredibly simple. Each Tales consists of several photographs (usually two or three but occasionally more and sometimes just one). In each iteration of the work, all of the photographs show the same subject and are taken from a single vantage point. In one work from the series, for example, we see a ship in front of an island and then, next to it, the same ship in front of the same island, shifted slightly toward the right of the image. In ‘Tales 36’ we see an Italian lake under a row boat, followed by the same lake with just the ripples left by the boat’s passing. Movement in these images is never seen but only implied. (Two points is all one need to make a line). These images are not important for their relationship to what is shown but their relationship to one another. Together, the images in each of Cramer’s Tales propose an entire closed universe: one thing and then another, between them much that is complex and invisible.

Cramer expands this idea in his exhibition 01-72, mounted in the gallery SALTS in Switzerland earlier this year. Here, the same logic of linearity that underscores Tales is obscured and threaded through an entire apartment building. The material for the piece is a series of 72 photographs taken of the surface of the Mediterranean ocean. The photographs were all taken in the moments before sunrise and show the water’s surface gradually becoming lighter. Visitors to the gallery, however, would only see one photograph hanging in the exhibition space. Each of the other seventy one photographs in the series were distributed about Haupstrasse 12, the apartment building in which SALTS is located. “For this project to be completed,” writes Cramer in a letter to the building’s residents, “I would like to ask your permission to install one photograph in each room of your apartment or store.” This question of permission is important, because Cramer’s project seeps into the private spaces of the building and its inhabitants. However we imagine his photographs in these apartments, it is the building’s inhabitants who will live with them. Cramer talks about treating the whole building as a sculpture and so by this logic, its residents and their daily routines become very much a part of the work. Recall from high-school science classes that any liquid will always spread out to take the shape of its container and suddenly the choice of seascape for the photographs starts to make sense at some base, pre-lingual level.

Despite the logistical complexity of 01-72, it retains the simplicity and intimacy of Cramer’s smaller projects. One gets the sense that the artist is interested in the limits of how little one needs to do in order to become present in a space. In a recent work in Dublin (‘Vestibule XVI’ (2014)), for example, Cramer buried an iron sphere in a park garden. Visitors to the park were told of the sphere but could not see it and so had to choose whether to believe the sculpture was present at all. In his studio, Cramer shows me a small jar of iron filings which constitute a new sculpture that will constantly expand in territory as small filings are blown about the gallery or get stuck to the shoes of visitors. In his single-copy book ‘Untitled (Moby Dick)’, Cramer takes the entire text of Melville’s seafaring classic, removes the punctuation and spaces between chapters and then has the entire text bracketed by 20 white pages at the beginning and 20 white pages at the end. The gesture is wilfully minimal but it completely redefines the shape and function of the novel (Cramer says he wanted to make the shape of the text “perfectly round, like a sphere”).

Such gestures obviously share a similar set of aims and techniques to many of the first generation of conceptual artists (Lucy Lippard’s writings on dematerialisation spring to mind) but to call Cramer’s work conceptual seems too vague and simplistic a description. His work has neither the revolutionary politics nor the academic distance that characterised the early conceptualists. Cramer’s works are too subjective and irrational and his aesthetic too constant to properly fit amongst that school. Sol Le Witt’s famous dictum that “the idea becomes a machine that creates the art” is countered by Cramer’s insistence that “the work never serves the concept” (and this for Le Witt et al. would mark the definite point of departure form “Capital C” conceptualism). Cramer’s works begin as concepts but are able to change shape and direction based on the observations of the artist. I have the impression, too, that this question of categorisation (a politics of naming) is not of any great importance to Cramer’s thinking. His interest is more in the subjective and intimate details of the work – a thin line traced between the mystical and the banal.

Artist Info

Writer Info

Henry Andersen is a composer and artist from Perth, Western Australia. He currently lives in Berlin.