Interview by Göksu Kunak; Sunday, Jun. 14, 2015

Examining the absurdities around her, artist Monira Al Qadiri mingles Middle Eastern traditions and spaces with Western iconography in a hybrid manner, while going beyond the well-worn clichés of these binary distinctions. In the expanded, queer realms of Qadiri, a veiled woman with a beard forces the viewer to contemplate sadness and narcissism, long-standing convictions about sex and gender are blurred in a kitsch music video of an old Kuwaiti song and, a bearded priest-like figure appears in a Japanese cemetery. In her more recent work, the artist has been dealing with politics in the Gulf region, focussing on oil trade and urban transformation. We caught up with her to discuss the performativity of gender, narcissism, and mass media religious propaganda.

Monira Al Qadiri – “Wa Waila” (Oh Torment), 2008. Short film, 10 minutes, film still ; Courtesy of the artist

Monira Al Qadiri – “Wa Waila” (Oh Torment), 2008. Short film, 10 minutes, film still ; Courtesy of the artist

Göksu Kunak: Drag − especially Elisabeth Freeman’s theory of temporal drag − is crucial in your works, such as ‘The Tragedy of Self’ series (2009-2011) or ‘Wa Waila (Oh Torment)’ (2018). As you mention in your artist statement for “The Tragedy of Self” (2009–11): “In my youth, I believed that to be someone in the public realm you had to be a man, so I toyed with this idea by repeatedly dressing up in male costumes and attire.” Tell us about your idea of drag. Do you think that drag can be revolutionary?

Monira Al Qadiri: For me personally, my fascination with drag started during the war in Kuwait (1990-91). I saw that all the men were out doing the fighting and resisting, and women were stuck indoors to protect their children and homes. As a seven year old at the time, this gave me the perverse impression that women were submissive and weak, and that men were “really cool” because they were doing things in the world and changing the status quo. This strange mental association I created between gender and “cool” transformed into an adoration for all things manly over time. I loved men so much that I wanted to “be” like them. Cropping my hair short, dressing up in drag, and putting on a fake moustache or beard just became a normal daily occurrence. There’s even an artwork by my sister Fatima Al Qadiri called ‘Bored, 1997’ (2008) in which my drag phase as a teenager is very apparent.

Eventually I grew out of it in my twenties, but it still fascinates me to this day how I linked gender to narcissism in my mind (and body) like that. That this obsession wasn’t so much about sexual confusion, rather than being a narcissistic impulse towards a social reality. That I had created a gendered response to conflict. This is why I still like to explore drag heavily in my work. I don’t have a clear answer as to why I do it, and that perpetual state of confusion is what keeps me fascinated.

In general I feel that drag has a very long history, especially when gender roles were not so categorized and defined as they are nowadays. I think that leaving gender undefined can harbor its revolutionary qualities, as people can find themselves accepting myriad expressions of it without giving it a title per se. If I label myself as a “cross-dresser” in my country I go to prison, whereas if I explore unnamable forms of drag in my art people find it somehow strange and comedic and it doesn’t get me in trouble. I can get away with so much because they think the work is ‘weird and funny’, and I’m definitely not the first person to juggle this blurry territory.

Monira Al Qadiri – “Abu Athiyya” (Father of Pain), 2013. Short film, 6.5 minutes, film still; Courtesy of the artist

Monira Al Qadiri – “Abu Athiyya” (Father of Pain), 2013. Short film, 6.5 minutes, film still; Courtesy of the artist

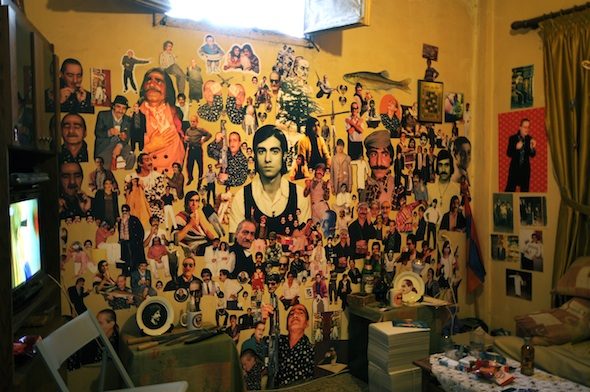

GK: In the installation ‘Anachronistic Fantastic’ (2013), as a part of X-Apartments Beirut, you covered the home of the hero of the Armenian neighborhood Klashin Boghos with his photos, badges and memorabilia. Herbert Marcuse sees Narcissus as an othered character, because he was punished as a result of falling in love with a man rather than accepting heteronormative values. At the end of the story, he again falls in love with another man, his own reflection, and turns into a flower after death. As narcissism is an important aspect of your work, how do you perceive this notion in contemporary society?

MQ: I think narcissism is still a very relevant topic in contemporary society, although the flamboyant macho hyper-individualistic form of it that was prevalent in the second half of the 20th century is somewhat out of date, hence the title “anachronistic”. What we are seeing as narcissism in the digital era is quite different to the “cult of personality” that characterized the narcissism of yesteryear.

In the Armenian ghetto of Beirut, I found Klashin Boghos – a 70 year old fisherman turned local celebrity – with his colorful silk shirts, pointy shoes, slick pony tail, and extravagant stories about his life adventures. He reminded me of that masculine type of self-worship I was once so enamored with. It only seemed right at the time to push that attitude towards its maximum effect (effectively creating a shrine of him inside his own apartment) and have people who entered there treat him like he was a real star. They would interview him, and have their photo taken together afterwards. Some people even believed the whole room was his creation, and that I was just his assistant sitting there.

Because, what is stardom anyway? Is it the sole privilege of the rich and famous, or can it be attributed to the funky fisherman down the street too? Who gets to be narcissistic in the world today?

Monira Al Qadiri – “Anachronistic Fantastic” (installation), 2013. Photographs, posters, badges, and cups installed inside private apartment, with performance, 4 m x 4 m room; Courtesy of the artist

Monira Al Qadiri – “Anachronistic Fantastic” (installation), 2013. Photographs, posters, badges, and cups installed inside private apartment, with performance, 4 m x 4 m room; Courtesy of the artist

GK: It’s often a fashionable topic to ask an Eastern woman about the headscarf and veil. What kind of cultural or societal questions do you face in relation to feminism and being a woman artist?

MQ: I consider myself “post-gender” as this is the only way to free ourselves from the male versus female binary. We will only be emancipated when the binary doesn’t matter anymore. I enjoy my position as an outsider in relation to the strict conditions of our societies. Nobody labels me a “woman artist” specifically because I am trying to escape the confines of these categories altogether. As for the veil, I am not interested in it, is all I can say. There is an unhealthy obsession with it in general.

GK: The painted murals and religious imagery on power generators in Kuwait were the starting point of your influential work ‘Muhawwil (Transformer)’ (2014). What are the other public spaces in the Arab Peninsula – or in other parts of the world you have been to − that are used for religious propaganda?

MQ: If you consider mosques public spaces, then they are the main arenas for instigating religious propaganda in the region. Because they are places of worship, the content of the sermons conducted there are usually off-limits to the authorities, so all kinds of bizarre religious and political ideas can be propagated and go completely unnoticed, or untouched. The frequency of these sermons obviously can influence the minds of generations of people, growing and spreading out of control.

Another ‘public space’ (if you can call it that) that I find disturbing is satellite television. There are hundreds of religious TV channels in Arabic, from all sides of the Islamic religious spectrum, continuously spewing messages of religious hate and intolerance, most notably of the sectarian kind. These channels influence and fuel sectarian wars and mindsets everywhere in the Arab world, and are often being aired from European cities, like London of all places. Sometimes I wonder why they aren’t controlled or banned yet. Though I think the powers that be often use them as tools to divide and rule their populations.

‘Muhawwil’ (Transformer) was a piece based on a short-lived visual experiment by fundamentalist charity organizations in Kuwait, who were sanctioned by the local government to “beautify” the streets by painting murals of moral and Islamic messages on the cube-like structure of electric power stations. Instead of the usual calligraphy, they used portraits of figures for the first time, contorting their bodies so that they don’t have a face – drawing faces would inspire idolatry in their view. It was eye-opening for me to see fundamentalists who are aggressively against anything artistic altogether would use figurative depictions like this. It was an experiment full of contradictions in many ways, but it was their own basic way to express creativity even within the strict interpretations they adhere to. It was as if they wanted to compete with modern-day visual culture, or even advertising.

Now that the government has fallen out of love with Islamists, these murals are being painted over again. In a way, I was able to capture this brief moment of religious artistic experimentation in public space before it quickly disappeared again.

Monira Al Qadiri – “Muhawwil” (Transformer), 2014. 4-channel video installation with wooden structure. 4 x 3 x 4 m; Courtesy of the artist

Monira Al Qadiri – “Muhawwil” (Transformer), 2014. 4-channel video installation with wooden structure. 4 x 3 x 4 m; Courtesy of the artist

GK: Lately in your works, you have been dealing with the oil market rather than the drag versions of yourself, and the dysfunctional nature of gender in society. What made you change your direction to economics?

MQ: Most of my work can be considered autobiographical. It is all like a self-portrait, whether it is directly using my face or body, or whether it is an abstract narrative or image alluding to my personal experience. My interest in oil is equally autobiographical. I come from the post-oil generation in the Gulf, never having experienced any semblance of what life looked like before this material invaded our local histories and psyches. Oil has rendered our history into some kind of fiction, always used as a PR device to showcase an engineered model of what cultural ‘heritage’ should be. In the work ‘Alien Technology’ (2014), I made a giant fiberglass sculpture of an oil drill, that was placed in a fake-looking heritage village in Dubai, next to some unused pearl diving boats. The personal connection here is that my grandfather was actually a singer on a pearl diving boat. Here, the pearling boat embodies his existence, in that he is the epitome of what the pre-oil world was about for hundreds of years: that harsh precarious life of easy death and poverty. The iridescent oil drill standing next to him was an embodiment of myself, so foreign an alien-like to the ecology, economy and history of this place.

Monira Al Qadiri – “Alien Technology”, 2014. Fiberglass sculpture, 3x3x2.5m // Courtesy of the artist

Monira Al Qadiri – “Alien Technology”, 2014. Fiberglass sculpture, 3x3x2.5m // Courtesy of the artist

As for the drag videos, they are still very much ongoing. I am working on the third iteration of the ‘Music To My Tears’ music video series that started with ‘Wa Waila (Oh Torment)’. Only this time, I will be wearing drag and lip-syncing to an Iranian female diva’s sad song in Farsi. I think the combination of drag with a woman’s operatic voice can give the piece another sense of added confusion, that will be equally beautiful as it is tragic.

Monira Al Qadiri – “The Tragedy of Self” (series 3), 2009. Photographs with gold leaf on canvas, 120×130 cm; Courtesy of the artist

Monira Al Qadiri – “The Tragedy of Self” (series 3), 2009. Photographs with gold leaf on canvas, 120×130 cm; Courtesy of the artist

GK: Considering your PhD dissertation about the aesthetics of sadness in the Middle East, what are your observations on rituals of sadness?

MQ: For this topic in particular, I was not really looking at gendered views of it. The idea was to flip the modern interpretation of sadness which is seen as a negative emotion, even a weakness or illness, whereas there is this huge history and tradition in middle-eastern culture that says quite the opposite. That sadness can be enlightening and even noble sometimes.

Men and women share equally in expressing their pain, but as often is the case, men’s expressions are much more well documented historically speaking.