Interview by Lee Escobedo in Berlin // Wednesday, Feb. 03, 2016

It consumes, absorbs, appropriates, without hesitancy and without judgment. The net is an impartial landfill for all our latent desires and anxieties. When harnessed, it can be a beautiful simulacrum of abstraction, a place where our dreams and nightmares become bedfellows, exploring what was, is, and can be. Iranian-born new media artist and thinker Morehshin Allahyari has taken up residence in America since 2007 as an educator, artist, and boundary-pusher. She received her MA in Digital Media Studies at the University of Denver and then received her MFA at the University of North Texas where she challenged the North Texas art community through her progressive, evolving body of work, exhibiting and lecturing at the Dallas Contemporary, OFG.XXX, and The Dallas Museum of Art. She has also held artist-in-residence positions at CMU Studio for Creative Inquiry (2015) and BANFF Centre (2013).

Portrait of Morehshin Allahyari // Courtesy of the artist

Allahyari now resides in Oakland, California where she is the Co-Founder and Assistant Curator in Research at the Experimental Research Lab at Pier 9/Autodesk in San Francisco and lecturer at San Jose State University. She is also co-founder with Daniel Rourke of the 3D Additivist Manifesto, a “call to push Additivist technologies to their absolute limits and beyond into the realm of the speculative, the provocative, and the weird.” I caught up with Allahyari before a new year that includes lectures and exhibitions around the world, in Toronto, Amsterdam, New Zealand, New York City, and more work on 3D printing activism, including the reproduction of destroyed Iranian artifacts by ISIS, that have generated her acclaim internationally for her vision and pronouncement.

Allahyari isn’t simply working in 3D printing. She is prodding, questioning, challenging and re-writing the philosophical implications of what can be created as well as what should be created. I met Allahyari while she was living and teaching in Dallas through a mutual friend, Kevin Ruben Jacobs, a Dallas-based curator and director of OFG.XXX, the first gallery to show and represent Allahyari.

Lee Escobedo: Let’s start by tracing back your earliest memories of your young life in Tehran. Were there any specific moments you can recall of seeing public art as a child?

Morehshin Allahyari: There was this park, Shafagh Park, close to our house in Tehran that my grandmother used to take me to all the time when I was a kid. I think my first memories of public art is from there. Here is a photo (totally creepy looking now).

LE: What was the political and social climate at that time? How did politics and religion play a role in your early world view? Especially of the West?

MA: Most of my childhood was in the post Iran-Iraq war. I think life for a lot of people was just starting to get a little bit better and perhaps less grey after eight years of war. One big advantage that I had was traveling to a lot of countries due to my mother’s job. So I got to see a lot of Europe, Asia and even the U.S. when I was growing up. That probably helped me to have a more balanced or realistic view of the West alongside other Western cultural products that I -like many other people in Iran – had access to.

LE: Describe the imagery that appears when the words school, childhood, family are used.

MA: This is a tough one. I think it’s a mix of good and bad imagery. My family was really liberal and open-minded. They gave me the best life I could possibly have in Iran. But school and outside society comes with mixed imagery. Some better than others. I sometimes think our elementary schools were more like the military. They were so strict about what we wore, the color of our socks, the length of our nails, whether we took tissues and glasses with us to school or not, that they would search our bags randomly every week to make sure we didn’t take videos or tapes or any kind of Western magazines or pictures to school. We had to stand in lines every fucking morning and sing this stuff about the religious leader. I think I hate those days of my life more than anything else.

LE: What did your work look like when you first entered college? What references were you pulling from in your work?

MA: Video art was what I started to work with mostly. Eventually I became more and more interested in experimental 3D animation. In terms of video art, I was specifically inspired by the work of artists like Pipilotti Rist, Joan Jonas, Vito Acconci, and Dennis Oppenheim. Also, I continue to gain a lot of perspective through the history and work of a lot of new media artists and colleagues.

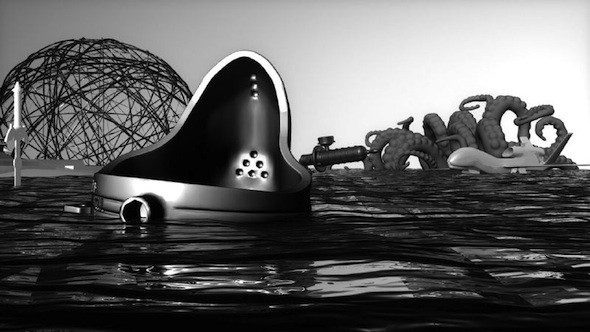

Morehshin Allahyari, (Dog with satellite): Dark Matter, 2014 // Courtesy of the artist

LE: What were the reasons behind your object choices for your series Dark Matter? Why were these objects chosen?

MA: All the objects chosen for the Dark Matter series are the objects/things that are unwelcome or forbidden in Iran. So I created a humorous juxtaposition of these objects by combining them in Maya and 3D printing them. The first series that received a lot of attention was a dog wearing a dildo with a satellite dish on top of it. A dog is considered dirty in Islam so they are not welcome in Iran and you might even get your dog taken away from you by the moral police if you walk them in the street. A dildo is obviously forbidden, and the government has banned the ownership of satellite dishes because you can have access to Western channels through them. But this doesn’t mean that people don’t own these things/objects. I have so many friends in Iran who have dogs. Almost everyone I know owns a satellite dish. So you know, the most interesting part to me is our relationship to something that is forbidden or forced out of our lives by the government, due to certain values or beliefs and this constant -perhaps unconscious- resistance by people to have access to these objects and own them. But also this very irrational aspect of things that are forbidden.

LE: What were some of the questions you were asking viewers, or even better, questions you hoped viewers would ask themselves?

MA: Well, obviously, if you don’t know the backstory, you will only see a weird juxtaposition of objects when you look at the work. I am totally fine with that. I think once you learn that these objects are chosen for a specific reason, then it adds a complete new dimension and perception to the work. I want the audience to experience that and also to think about these 3D printed sculptures as a collection/documentation of a certain period of time and our relationship to forbidden/unwelcome/tabooed objects or things.

Morehshin Allahyari and Daniel Rourke, Still from 3D Additivist Manifesto, 2015 // Courtesy of the artist

LE: The Additivist Manifesto that you co-founded with Daniel Rourke has gained traction across the Internet and is being included in group exhibitions and talks across the world. What misconceptions have you found in the project compared to what you and Daniel are attempting to create?

MA: I would say irony and dark humor might be the easiest ones to miss, which was something that we talked about a lot during the writing of the text, the recording of the audio, and the making of the video. If you look at the history of manifestos in general, irony and contradictory statements and concepts have always been some of the most common aspects. By now, we have done tons of press, interviews, workshops, and talks presenting our video and project at universities, galleries, and different organizations across the world and every time it’s been really interesting to see how people react after watching the video. When you hear people giggle at the crazy long list that we have in the video, versus the what-the-fuck faces at the end, versus people just being excited or weirded out. When people understand the irony and dark humor in our video, they respond very differently than when they don’t, and I love this component of our project. How it lies on these very non-binary lines of seriousness and humor, real and unreal, utopian and dystopian. To us, it’s all of that and none of it.

LE: Where did you meet Rourke and how did the collaboration manifest?

MA: Daniel did an interview with me for Rhizome’s artist profile and a big portion of that interview was around my Dark Matter series, 3D printing, and censorship. Some months later we were both in Chicago for a CAA conference and we continued the conversation around 3D printing and talked about our frustration around its hype and all the super cheesy and uninspiring uses of 3D printers. We briefly talked about doing a project around that and we continued the conversation online and came up with the idea of a “manifesto”, as well as a “cookbook”, inspired by the Anarchist Cookbook by William Powell.

LE: How did this inspire the impetus for an actual cookbook component for your philosophy?

MA: In March 2015 we released The 3D Additivist Manifesto. The Manifesto posits a series of profound problems, including environmental catastrophe, social and economic inequality, and the continued co-option of radical thinking by the market under the guise of innovation. To consider each of these problems we ask the audience to resist their own human-ness, and in so doing, truly let loose their creative capacities towards an unbounded, though often terrifying, post-human future. We then opened up submissions to a radical ‘3D Additivist Cookbook’ of blueprints, designs, 3D print templates, and essays on the topics raised by our Manifesto, including contemporary approaches to sculpture, digital materiality, and design. Throughout 2015 over 100 leading international artists, makers and theorists submitted essays, 3D printable designs, and other speculative materials to our #Additivism project. We believe radical approaches to technology can open up new perspectives, providing us with the means to challenge preconceived ideas. We plan to publish The Cookbook in a digital edition in mid-2016. The final Cookbook will then act as an ‘open-source’ informational vehicle and archive for both critical ideas and the practical means of realizing those ideas, able to flow freely and pass from hand to hand, email inbox to email inbox, very much in the tradition of early photocopied punk zines and radical pamphlets.

LE: Describe the intersection of both your works that fostered the collaboration?

MA: Daniel comes from a philosophy and writing background. He is currently doing his practice-based PhD at Goldsmiths University’s Department of Art. His research focuses on the intersection between digital materiality, the arts, and posthumanism, in search of alternative or radical structures for thinking and doing. I come from a Social Science and New Media Art background and my practice revolves around political and social issues we face every day, mostly focused on the Middle-East and bringing together art and activism in meaningful ways. I have been working on a couple of projects that attempt to use 3D printing in a critical and poetic way, including my Dark Matter series and a new in-process project called Material Speculation:ISIS. In developing the concepts, gathering resources and ideas, we worked closely and side by side (virtually) in deciding what topics, theories, and items we wanted to include in our Manifesto. We spent months writing, editing, and adding to our text in a series of Google Drive documents. I think both of our backgrounds and our current research and practice have played an important role in the development of the Manifesto and the current growth of the Cookbook.

The 3D Additivist Manifesto from Morehshin Allahyari on Vimeo.

LE: I’m curious about the software you and Rourke used to create the video for The 3D Additivist Manifesto. What did you use to create it and what concepts and aesthetics did you want the video to have?

MA: The main software we used to create the animation was the program, Maya. By juxtaposing the script, visuals, and sound of the Manifesto we wanted to create a work that resisted itself. The Manifesto attempts to circumvent its own authority, exhibiting all the malleability and monstrosity of plastic, and the rich viscosity of dark, ancient, crude oil. Only then could it possibly succeed us, its writers, and begin working of its own accord. The language we chose, and the images we injected into the video, are science fictional in form and intent. But it is perhaps the list of radical objects that does the majority of the post-human, inhuman weirding of the Manifesto. It keeps growing until it ascends to monstrous proportions, until it exceeds language, and grows bigger than words can signal. Both the visuals and sound create an emotional and poetic possibility for rethinking, reacting and resisting the political conditions of our time. We ask our audience to consider ideas so radically ‘outside’ of human comprehension, that only the language of horror and nightmares can evoke them. The voice of the video itself, which was created by the amazing sound designer and composer Andrea Young (in addition to the sound in our video), resists being male, female, cyborg or human, mutating and feeding back on itself as it grows in stature.

LE: How has the transition been leaving Dallas and relocating to San Francisco? Is the creative energy in San Francisco more palpable than here?

MA: The transition has been an interesting one. I don’t think I have ever considered myself a -local- artist based in one city. I find my practice to be more international and universal in a way that my location has not had a big influence on its level of production or exposure. Maybe that’s also because I am an artist in diaspora. I have travelled and moved so much that I don’t necessarily have a “base” or “home”. I make my work for an international audience. I want anyone from any background and culture to be able to connect to it.

Morehshin Allahyari, Material Speculation: ISIS, King Uthal, 2015 // Courtesy of the artist

LE: When I first encountered your work in 2012, it dealt with socio-economic issues concerning your birthplace, Iran, femininity, censorship and the Internet as a studio for rebellion. As your focus has become narrower, with the Additivist Manifesto and the 3D printed work you have recently shown, the situation concerning xenophobia and Islamophobia is boiling over in America. How does this political climate influence your work, or, its direction?

MA: My practice has always been influenced and inspired by the life I live and my experiences as an Iranian, a woman, a woman of color, an activist who is self-exiled. These personal, political, emotional and daily issues are what I have used as a point of departure in all of my work. I am currently interested in 3D printing and the radical, invisible, censored aspects of it because of the research I’ve been doing in the last two years, which is very much inspired by scholars like Donna Haraway and Reza Negarestani. I want my work to respond to and resist and criticize the current political and cultural situation that we as humans are experiencing on a daily basis and I see 3D printing a medium that currently gives me that voice.

LE: And what do you have planned for 2016 in terms of exhibitions and lectures?

MA: This year is already filled up with shows and talks and workshops all around the world. Some of the immediate upcoming events are a solo exhibition at Trinity Square Video gallery in Toronto where I will be showing a completed version of my Material Speculation: ISIS project for the first time, opening on February 11th. I will then be in Amsterdam at the end of February to do a workshop and talk about #Additivism with Daniel Rourke at Sonic Acts 2016.

Artist Info

Exhibition

TRANSMEDIALE

Group Show: ‘Disnovation Research / Drone-2000’ feat. #Additivism

Panel: Feb. 04, 2016

John-Foster-Dulles-Allee 10, 10557 Berlin, click here for map

TRINITY SQUARE VIDEO

Morehshin Allahyari: ‘Material Speculation’

Exhibition: Feb. 11 – Mar. 19, 2016

401 Richmond St W. Suite 376, Toronto, click here for map

Writer Info

Lee Escobedo is a Dallas-based, critic, curator, and founder of the award-winning Texas arts publication, THRWD Magazine.