To close your eyes is to forget her perfectly symmetrical yet generic face. To try to sing one of her hundreds of thousands of songs becomes a loss of words. It is no easier to try to replicate any of her MikuMikuDance freeware moves either. The most likely to stay with you is the image of her long flowing turquoise locks, and the uncomfortable fact that you’ve almost accidentally seen up her skirt. CTM and transmediale’s co-production Still Be Here uses the synthesized, crowded-sourced idol Hatsune Miku as a nearly blank slate on which complex layers of art, identity and gender are mounted and questioned. The result is a much less forgettable journey through corporations, fans and connections which all hold an integral role in the formation and rise this the postdigital pop star.

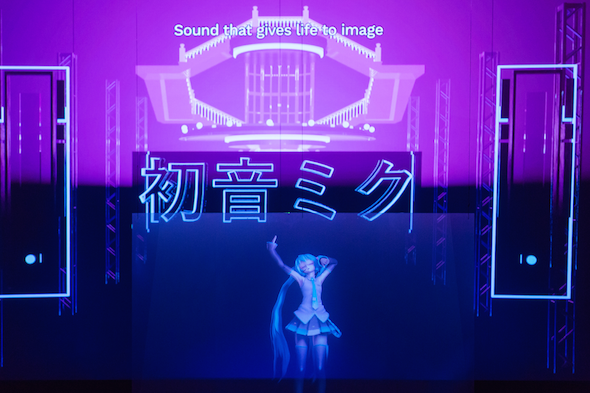

Hatsune Miku, Still Be Here performance at CTM Festival 2016 // Courtesy of Mari Matsutoya and CTM + transmediale

In the introductory scene, Hatsune Miku emerges form a screen projecting Japanese symbols, and appears as a character still in physical development. Miku assumes the voice of various narrators in the show, including Vocaloid software representatives, who talk about the star’s inception and growth first as a marketing tactic, and then as a pop phenomenon. If there is a depth to Miku’s cultural background, as the initiator of the project Mari Matsutoya explains, it is around the particular political and economic facets of Japan’s entertainment industry, which she sees “as a massive marketing feat that is very sensitive to how it is perceived by its global peers, selling them the image they want to see. A true soft power.”

Hatsune Miku was not made for the Still Be Here performance: she is the brainchild of illustrator Kei, and her most jarring physical attributes are that she has been 16 years old since 2007, and that she weighs 42kg and is 158cm tall. She is able to appear in Still Be Here because – as the viewers were informed before the show – under the CC-BY-NC license her image can be appropriated if she isn’t devalued and her presence is not for commercial gain. This principle in the performance makes for both a questionable and inviting factor. The audience members are forced to reflect about the extent to which the show is allowed to be critical before it becomes devaluing, and therefore people can only assume that some things are left unsaid. The closest the piece actually comes to lowering the value of this singer is placing her in front of images of commercial junk food. But by the same stroke, this forces viewers to fill in the blanks with their own interpretations of her identity and how it’s linked to corporate law. For example, why is it so easy to get a glimpse of the 16 year old’s underwear, yet projecting her in a potentially-profitable light is a prosecutable offence? However, if you think Miku’s identity is concretely and inescapably female, then you are wrong.

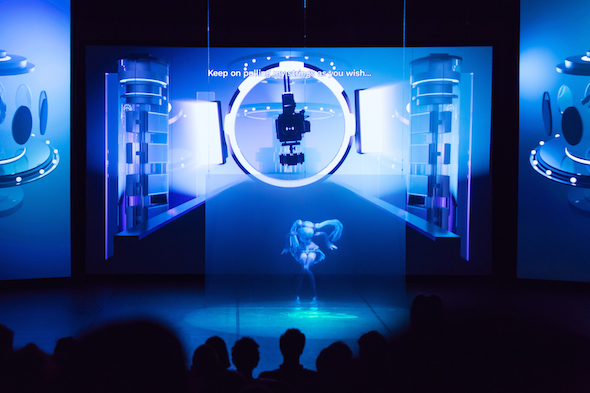

Hatsune Miku, Still Be Here performance at CTM Festival 2016 // Courtesy of Mari Matsutoya and CTM + transmediale

Hatsune Miku, Still Be Here performance at CTM Festival 2016 // Courtesy of Mari Matsutoya, CTM + transmediale

Since Hatsune Miku has been around for almost a decade, her persona and image has been adored and adopted by many as she has performed for audiences in Tokyo, New York, Los Angeles and beyond, while professional and amateur writers are creating new original songs for her continuously. Still Be Here examines this as it focuses in on German cosplayer and math teacher Rudolf Arnold, who takes many liberties in understanding Miku’s character just as the viewers must during the show. His initial preoccupation with the character arose out of her versatility, so it’s no wonder that his rendition of her image includes himself with a voice changer, jetpack, space-like helmet, and speakers, making the pop star’s image seem more transformer than teen pop princess. If Miku can be all that at once, then she can be virtually anything.

The show ends amid a mournful atmosphere. Though Miku is a projection created by sophisticated software made to only replicate emotion, the sentiments of the creators of the show can be felt through their control of the star. While most words coming from Miku’s mouth have been a mild mash up of lyrics that she actually sings, towards the end the words become an acknowledgement of the fact that she is like a puppet to the masses, without any power of her own. Although Miku has been used in many cases for the enjoyment and expression of many desires, we are left thinking about what toll that role in society would take on her, if she was real. While she may not be a real person, stars do exist: in feeling a connection to them in a capitalist society, we then question what implications our desires have on these authentic human beings and their seemingly creative output.

Hatsune Miku, Still Be Here performance at CTM Festival 2016 // Courtesy of Mari Matsutoya and CTM + transmediale

Exhibition

CTM and transmediale

Hatsune Miku: ‘Still Be Here’

Mari Matsutoya, Laurel Halo, Darren Johnston, LaTurbo Avedon, and Martin Sulzer