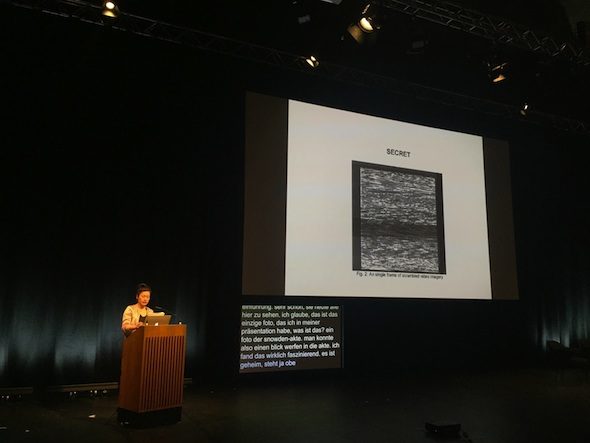

In the last keynote conversation of transmediale 2016, Hito Steyerl presented a perplexing image to the audience. The classified material leaked by Edward Snowden seemingly presents little more than static, or noise. Encrypted, the image would traditionally require machine decryption to be read. But instead of revealing the photograph concealed behind it, Steyerl referred to an internal NSA website posting, where an analyst describes a sea of data in which she is afraid she might drown. In an act of apophenia – or active misrecognition refusing to see the obvious – Steyerl argued that the noisy image does not require decryption to reveal its signal: the noise is the signal. It depicts precisely the sea of data in which we are all drowning. Divided into four streams — Anxious to Act, Anxious to Make, Anxious to Share and Anxious to Secure — transmediale/conversationpiece confronted post-anthropocene complexity to explore ways of moving through the information overload: the sea of data.

Hito Steyerl, Keynote Conversation, Anxious to Act at transmediale 2016, HKW Berlin // Photo by Nadine Roestenburg

Featuring simultaneous multithreading, this year’s transmediale inundated its participants with a multitude of parallel conversations, constantly overlapping and frequently contiguous. It was impossible to participate in everything, so individual selection became a practical necessity — choose your own adventure. The knowledge gaps that subsequently manifested were intended to be confronted in self-initiated conversations outside the programmed events. Yet, curiously, the festival’s designers seem to have overlooked the fact that their core concept, anxiety, is an embodied experience. For some, participation meant running from event to event, arriving late and leaving early, skipping meals and taking refuge in privacy, dismissing the recurring invitation to continue the conversation. For others with realistic expectations, shallow pockets or just a healthy distance, not being an organizer, festival pass-holder or microphone-toting volunteer did the trick.

Formal criticism aside, the adventure I chose was dynamic, challenging, informative and definitely worthwhile. I had the privilege of joining a workshop titled ‘Exploring Planetary Scale Design,’ where participants came from diverse backgrounds and practices, each interested in the topic from his or her own expert perspective. The workshop, which was gamified to the extent that it began to resemble a LARP, consisted of a fast-paced series of communicative exercises. It was an unrelenting, cognitive workout complete with a timekeeper, and it hinted at the complexity of approaching design practice on a planetary scale. Directly afterwards, I attended the four-hour-long ‘Market Uncertainty’ panel discussion (branded as a ‘panic room session’), moderated by Elvia Wilk and Helen Kaplinsky. The open discussion sought to pin down a variety of terms frequently used in reference to the market and its uncertainty, especially within the fields intersected by transmediale: art, culture and technology. While the discussion occasionally veered into techno-utopianism, it was grounded in earnest concerns about the material substrate of global communication, whether centralized, distributed or decentralized. Who owns the undersea cables linking us together, and who holds the switch?

Keller Easterling Keynote Conversation, Anxious to Share at transmediale 2016, HKW Berlin // Photo by Julian Paul

The prevailing mindset held by the evening keynote presenters was that of necessary intervention. Eyal Weizman, in conversation with Keller Easterling and Brian Holmes, declared that we must accept our complicity and turn critique inward, not outward. While Easterling, whose writing is pitched toward designers with the agency to change infrastructure, showed us the “everyday violence” that precedes collapse, Weizman explored the technical possibility of knowing the truth as a mode of engagement. Isabell Lorey’s Foucauldian analysis of the European refugee crisis criticized the recent resurfacing of patriarchy in Europe and praised the feminist research and activism initiative Precarias a la Deriva for demanding the right to care and be cared for. Nicholas Mirzoeff discovered a common denominator between the Black Lives Matter movement and Palestinians: love.

If we are all drowning in a sea of data, is it possible to design a life vest? What would a data flotation device look like? In the words of Hito Steyerl, solidarity must be an act of apophenia. More exactly: it must be a suspension of difference in the light of a generative fiction. Are the machines developed under and in the service of the prevailing economic system prepared for or even capable of emancipating the world’s society? Surely, a data flotation device would be made out of “dirty data” or noise. It would not be a static object, but it would be an active form.

Keynote ‘Anxious to Secure’ with Isabell Lorey & David Lyon, transmediale 2016, HKW Berlin // Photo by Julian Paul

Exhibition

transmediale/conversationpiece

Festival: Feb. 3 – 7, 2016

HKW Berlin, click here for map