The legacy of Rachel Lowe Lambert Lloyd Mellon is the subject of Rachel Alliston’s exhibition ‘Property of a Private Collection’ at Centrum. Mellon, known to friends and various cultural icons as ‘Bunny’, is an exemplar of a particular generation of the American aristocracy, whose influence is as pervasive as it is invisible. This tension between power, visibility and identity is a leitmotif that infuses Alliston’s engrossing exhibition.

If Mellon’s name is known, it is most likely because of her role as the prime creative mover behind the redesign of the Rose Garden of the White House, the meticulously maintained backdrop for dozens of historically significant photo ops that have come to define American culture. Despite this cultural contribution, Mellon self-consciously kept her profile low, which, in some ways could be thought of as her greatest achievement given that she was closely connected to some of the most high-profile people moving in the most rarified social circles, in the most powerful country the world had ever known. But then, it is never truly a surprise when a woman’s achievements aren’t widely acknowledged in the face of the monolithic indifference of patriarchy. And the US of Mellon’s time was an unapologetically patriarchal nation. For all the disruptive power of the first and early second waves of American Feminism, it should not be forgotten that women in certain American states could not even have individual bank accounts until well into the 1970s.

Rachel Alliston: ‘Property of a Private Collection’, installation view, Centrum Berlin // Photo by Ute Klein, Courtesy of Centrum

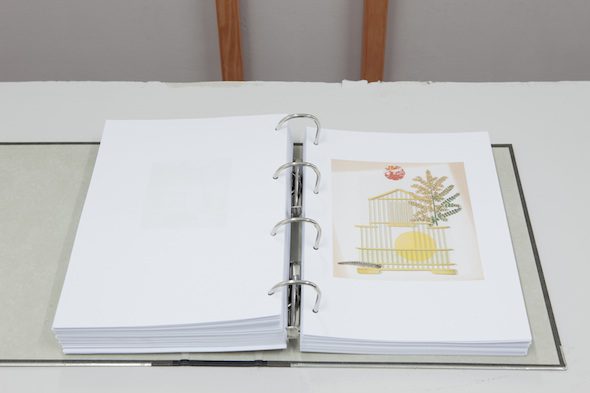

The aesthetic of the domestic, replete with claustrophobia and defeated ambition infuses ‘Property of a Private Collection’. The walls are adorned with prints based on drawings by the botanist and artist Gerard van Spaendonck, whose ‘Album of Flower Studies’ made up part of Mellon’s extensive library of works on gardens and gardening. The longstanding metaphoric connection between female sexual identity and carefully manicured gardens – the most unnatural possible format for experiencing nature – is, of course, never far from the mind in seeing the works of ‘Property of a Private Collection’. But the ambiguity of what is disclosed and what is not—between Mellon’s understanding of her private and public identity – is in many ways an acknowledged and embraced aspect of the show. Mellon’s home and its contents (and its occupants) are also the subjects of an artist’s book produced for the exhibition. Consisting of hundreds of images of the objects Mellon and her husband collected over their long lives together, the book is also a document chronicling the America of their time. Alongside the pictures of Mellon’s extensive collection of opulent silver and ceramic wares, and portraits of her with her husband Paul, the viewer can see the faces of the African American workers who ploughed the soil of Mellon’s serene Rose Garden.

The dynamics of privilege are another important theme the exhibition explores. The centrepiece of ‘Property of a Private Collection’ is a video work, in which Alliston weaves together various threads of Mellon’s biography and then considers the tensions in the resulting tapestry. The film begins with a litany of numbers being read by a computerised female voice. The numbers appear somewhat random until you learn that they are the pages on which Rachel Mellon’s name appears in her husband’s autobiography. The life of ‘Bunny’ Mellon, Alliston reminds viewers, is largely known to us through the eyes of her male intimates and acquaintances. In the film, two female actors appear, reading excerpts from Paul Mellon’s autobiography, as well as interviews with Rachel Mellon, and, in some instances, text ostensibly by Rachel Mellon but which Alliston has, herself, written. This consciously marked mediation lends a pervading sense of tragedy to the film: however private Mellon may have sought to be, the fact that interested researchers will encounter most of the salient facts of the life of such an influential figure from American cultural history at one remove (at least) reifies the voicelessness that countless, even more thoroughly disempowered 20th-century women must have felt.

Rachel Alliston: ‘Property of a Private Collection’, Installation view at Centrum // Photo by Ute Klein, Courtesy of Centrum Berlin

There is a strong sense of institutional critique across the works. Mellon’s peace with her role as society doyenne is deeply troubling in a year when a woman candidate is poised be the next person giving press conferences in the garden that is Mellon’s most famous creation. Alliston’s video dwells on the strange thrall the erstwhile Democratic presidential hopeful, and uber-sleaze, Jonathan Edwards, seemed to exert over Mellon. Running against Hillary Clinton in 2008, Edwards was eventually outed for an adulterous affair in which he fathered a child as his wife, Elizabeth, battled terminal cancer, while, at the same time, expending hours on the campaign trail on her philandering husband’s behalf. Mellon, the video notes, called Edwards’ campaign office in order to donate money but was initially treated with patronising dismissiveness. Plus ça change…The overarching sense of unease extends to cultural institutions.

Alliston’s artist book seems to satirise the anodyne neutrality affected by exhibition catalogues, a bit of japery all the more apropos when the viewer considers that Mellon’s assets were dispersed over the course of four separate auctions at Sotheby’s. To be at home with power, though, is not the same thing as to be empowered. Whether or not Paul Mellon promised Rachel a rose garden, she certainly built her own, the question ‘Property of a Private Collection’ seems to pose is whether in the meticulous, ordered harmonies she created her status as an autonomous being was lost amid the perfect petals and branches.

Rachel Alliston: ‘Property of a Private Collection’, Installation view at Centrum // Photo by Ute Klein, Courtesy of Centrum Berlin

Exhibition

CENTRUM BERLIN

Rachel Alliston: ‘Property of a Private Collection’

Exhibition: Feb. 20–Mar. 20, 2016

Reuterstrasse 7, 12053, Berlin, click here for map