Interview by Penny Rafferty in Berlin // Wednesday, Apr. 06, 2016

The body in art has always been a contested issue in terms of representation, but it is also central to how we understand our identities, through gender, race, sexuality and ethnicity. People use the body as a source of expression, modifying it to align with or rebel against others’ ideas and prejudices. American artist Doreen Garner is unique in the way she dismembers the body in her installations, leaving only organs and carrion to transmit her messages to viewers. Berlin Art Link talked to Garner about fetishization, white supremacy and unethical medical practices.

Doreen Garner, Video Still from ‘The Observatory’, 2014 // Courtesy of the artist

Penny Rafferty: Let’s start with your website: you enter by clicking on the a button that says Examine.

Doreen Garner: When I enter a site, I always try to dissect the layers to find the artist’s voice and practice in between this unified template we know as the Internet. So I decided to invite the viewer to examine my work, the way I do others’: by dissection.

PR: Dissection plays a strong part in your work and use of materials. It’s very intriguing the way you map race, gender and social economy through your organic objects.

DG: My materials are all in tune with what I feel the eye is drawn to, we are attracted to wet glossy materials – I use a lot of silicon, which is the closest material to skin. Many of my configurations can be visualized as sex toys, dildos, etc. They somehow conjure up ideas of masturbation and sexual fetishization, maybe because of who I am as an artist or maybe because the viewer wants to see this in my work. However, I often find myself being looked at with the same gaze that’s afforded to my work. The art world and society are making black women into sexualized objects: just look at the media for confirmation.

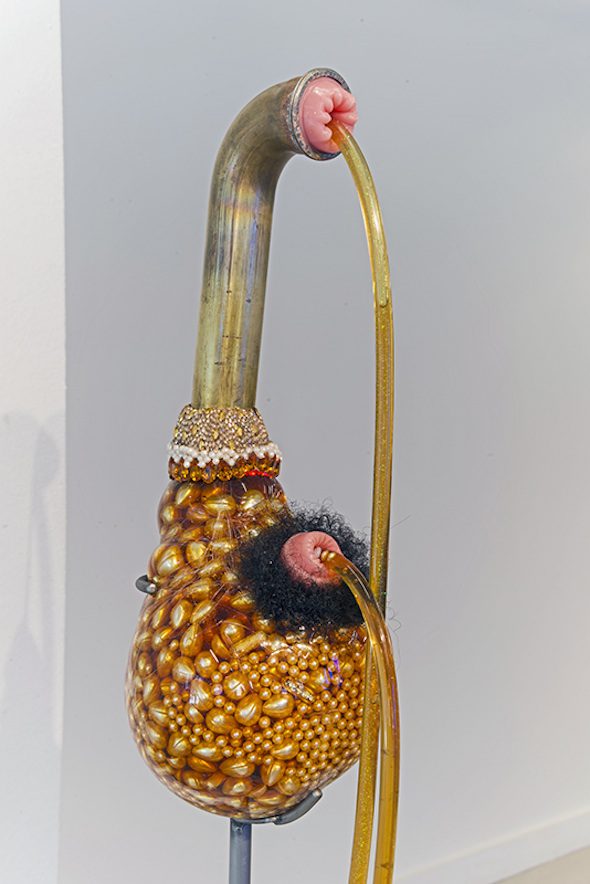

Doreen Garner: ‘Onika’, 2014 // Courtesy of the artist

PR: Is this something you are going into further in your new works?

DG: Well, at present I’m using a lot of medical practices and elements in my work, ripping up, sewing back together and re-examining the materials. A lot of my research is coming from the horrendous activities of James Marion Sims (1813–1883). He was an American physician and glorified as a pioneer within his field and often dubbed The Father of Modern Gynecology. His most significant work was developed around repairing the vesicovaginal fistula, which is common after complicated childbirth: it rips the wall of the bladder, creating further complications. However, Sims made a huge name for himself from the expense of thousands of enslaved African-American women he used as guinea pigs, many of whom died. They were left to bleed out after his operations in old shacks without anesthetics, because he said black women have a higher pain threshold so don’t need to be anesthetized during these experiments. He also performed many unnecessary procedures, such as cracking black babies skulls when they were still alive to monitor brain growth, and literally sawing off the jaw of a black man as he supposedly had cancer growing inside it. All of these experiments were done with force, without consent and with a jovial atmosphere from the doctors involved.

PR: I can see this being very difficult for the white art world to stomach.

DG: Yes. Well there is a growing positive interest in black culture, black lives and the black body in the contemporary art world but at times I often feel cynical of the individuals who are representing/offering it. There is now money to be made in this field and that usually disinherits the community and dilutes the culture. Take black music culture, like rap and hip hop, for a perfect example. I see these artists who make money off of our culture as agents of white supremacy, not mediators of culture.

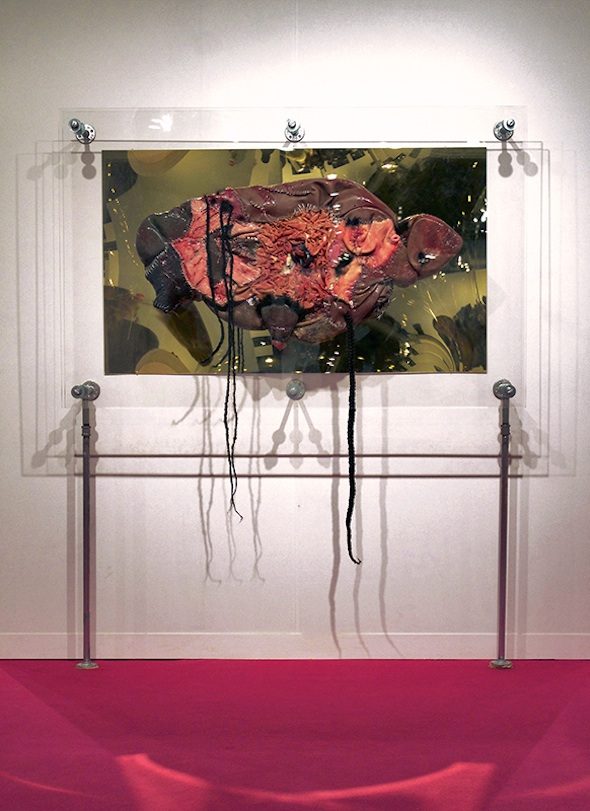

“Not only had Sims to close the natural openings in the ravaged vaginal tissues; he had to make the

edges of these openings knit together. He opted to abrade or scarify the edges of the vaginal tears

every time he attempted to repair an opening. He then closed them with sutures and saw them

become infected and reopen, painfully, every time.”, 2016 // Courtesy of the artist

PR: You said in a recent interview that you wonder if the works would be read the same if a white woman made them. Can you elaborate on that?

DG: Well, if I was a white woman I could create work about my race but it would never be talked about because being white is seen as neutral, normal and standardized. Because I’m a black woman my work is often seen to be sexual and illicit and that becomes my practice.

Doreen Garner: ‘Vesico Vaginal Fistula’, 2016 // Courtesy of the artist

PR: This can refer back to your work ‘The Observatory’, right? And your retaliation against the white gaze…or maybe stare is more appropriate.

DG: Yeah, in the performance entitled ‘The Observatory’ I’m in a glass box and I stare at the audience as they look at me, I single people out and watch them. They often try to deflect by talking to a friend or moving around the room but I follow them and I don’t stop following them.

Doreen Garner: ‘Pickled Pearl’, 2015 // Courtesy of the artist

It all started with a book I am writing with Kenya (Robinson) called ‘Clarified Hateration’, which explored the reasoning behind why we personally have zero tolerance for bullshit today. I think, personally, mine comes from my sister: when she was 8 years-old she had an AVM rupture that resulted in a stroke, which left her with the inability to walk and talk. Her face was severely distorted, but naturally she wanted to still do all the things she had done before, like going to the zoo. But people stared – children, adults alike – and I felt powerless to stop them. I was only two years older than her. A lot of my work is aimed at getting even and creating a power dynamic critique for her. She died in 2007.

PR: Your works are riddled with tumors and sores, but they adorn themselves in this fight against some inevitable disease. A kind of ego comes out of them: strong willed and triumphant.

DG: They are very much a part of my personality. To go through a funeral without crying is very intense. My family was ripped apart and, in turn, so was my life. I’m left with two components: sadness and beauty.