Article by Nora Kovacs // July 19, 2016

This past week, Site Santa Fe opened its doors to the public for its second Sitelines biennial exhibition, titled ‘much wider than a line’. Featuring 35 artists from 16 different countries, Sitelines seeks to reimagine the notion of a biennial and leave behind the pretension that often accompanies such a large-scale production. Instead of having a representative artist from each country showcase his/her work, which may or may not pertain to a declared theme, Sitelines takes a more concentrated approach by focusing on art of the Americas and maintaining a common thread between each artist and their artwork. A diverse curatorial team, consisting of Rocío Aranda-Alvarado, Kathleen Ash-Milby, Pip Day, Pablo León de la Barra, and Kiki Mazzucchelli, have hand-picked each of the artists for a particular reason and drawn parallels between them to demonstrate that the physical and metaphorical boundaries between countries, territories, cultures, landscapes and, between humans and nature, really are much wider than a line.

Juana Valdes: ‘Sienna Colored China Rags’, 2012, porcelain bone china // Courtesy of the artist and Site Santa Fe

Each artist contributes a unique and powerful voice to this year’s Sitelines, whether it be Cuban artist Juana Valdes’s conceptual commentary on her experience as a Cuban immigrant to the United States and the social/racial expectations that that entails, or Xenobia Bailey’s hand-crocheted meditations on African-American material culture and the overlooked significance of the African-American homemaker. By narrowing the scope of the biennial to the Americas, SITElines 2016 has somehow managed to circulate an even deeper range of cultural and political narratives than most other biennials at the moment. It is diverse, inclusive, and provocative in the most genuine of ways, and the exhibition’s ongoing dialogue surrounding nature and our relationship to it is an example of its refreshingly “down to earth” approach.

Xenobia Bailey: ‘Sistah Paradise’s Great Walls of Fire Revival Tent and the Aesthetic of Funk’ (2002 – ongoing), Cotton and acrylic yarn, metal frame, electrical tape, shells // Courtesy of the artist and Site Santa Fe

Sitelines, like most of the other exhibitions put on by Site, makes a point of acknowledging its geographical context. Site is not just a contemporary art space for big names to shuffle in and out of, but a contemporary art space in Santa Fe, New Mexico, a place of immense cultural overlap. Site addresses this complicated positioning with each exhibition that it welcomes into the space and this year’s Sitelines is no exception. Not only have many of the artists created site-specific works for the biennial, but a handful of local artists are also showcased in the exhibition to reflect Santa Fe’s social and political climate.

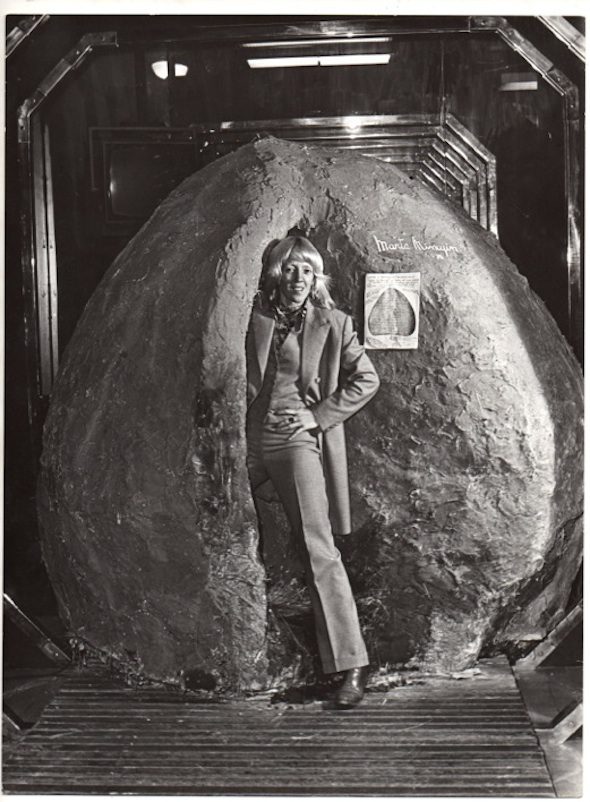

In one of the first galleries, Argentinian phenomenon Marta Minujin presents us with ‘Comunicando con Tierra’, a 1976 piece that she has recreated for this year’s biennial. The work centers around the idea that earth is a unifying factor among humans and that we are able to communicate with and through it. Minujin sees art as a protective force and she has thus created a human-size nest for visitors to walk around and inside of. Made of adobe, mud, and straw, the nest is modelled after the ones that sparrows forage after it rains in arid regions. Minujin began the project in 1976 by sending earth from Machu Picchu to artists around the world and asked for earth in return. She then filmed herself covering her body in this earth from various areas and these films can be seen inside of the mud nest at Sitelines 2016. Minujin highlights the protective power of nature and its elements through her work, underlining how we find solace from the simplest and most natural materials and processes.

In contrast to this appreciative viewpoint are Minnesotan artist Aaron Dysart’s works, ‘Preserve’ and ‘Second Growth’. Dysart’s pieces are pointedly critical of how humans interact with nature. ‘Preserve’, which consists of two altered tree branches, explores the problematic division we have placed between ourselves and nature, primarily as a means to control nature for our own benefit. One of the branches has been smoothed out and “perfected” with auto body primer and filler, while the other has been encased in aluminum foil to give it a more “valuable” look and feel.

Marta Minujin: ‘Comunicando con Tierra’ (1976, 2016), documents, photos, earth construction, video // Courtesy of the artist and Henrique Faria, New York & Beunos Aires

‘Second Growth’, on the other hand, is described as a “live tree installation” and appears as though a pine tree has quite literally fallen through the walls of the gallery. Illuminated by a skylight from above, the tree has continued to grow and thrive since its installation, forming a discourse around our desire to control and tame nature and its subsequent “encroachment” upon what we have deemed our space.

Aaron Dysart: ‘Preserve 2’, 2015, Wood, aluminum foil, // Courtesy of the artist

Alaskan artist Sonya Kelliher-Combs explores a similar interplay between the man-made and the natural. Her works make up a series, titled ‘Remnant’, in which she incorporates traditional practices of tanning and hiding to encase various objects behind a sort of ‘skin’. From bones and antlers to polar bear fur, human hair, and seal intestine, her works are reminiscent of archeological findings and bring into question Western notions of beauty, and what should or should not be framed as art in a museum or gallery setting.

Sonya Kelliher-Combs: ‘Remnant- Muskox Fur’, 2016 // Courtesy of the artist and Site Santa Fe

No conversation about ‘much wider than a line’ can be complete without discussing the inclusion of native and indigenous artists/subjects in the biennial and the chronicles of nature therein. From Zacharias Kunuk’s enthralling film about the traditions and dynamics of Inuit life and Anishinaabe artist Maria Hupfield’s immersive performance art to the re-imaginings of traditional native practices in Jorge González’s woven chairs and Erika Verzutti’s wooden totems, there is a undeniably powerful discourse occurring in SITElines 2016 that not many other biennials can claim. ‘Much wider than a line’ has indigenous knowledge, histories, and cosmologies running through its roots, and nature plays a central role in those narratives.

Maria Hupfield: Still from ‘It is Never Just about Sustenance or Pleasure, 2016, video installation, hand-sewn industrial felt sculpture worn on the body with accompanying performance // Courtesy of the artist and SITE Santa Fe

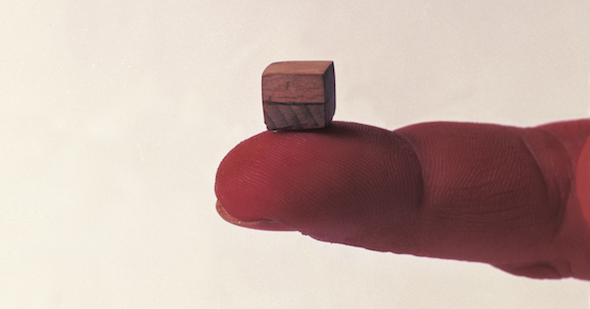

Cildo Meireles: ‘Cruzeiro du Sol’, 1969-70, oak and pine cube // Courtesy of Site Santa Fe

The biennial comes to a close or, rather, full circle with ‘Cruzeiro du Sol’, a work of “humiliminimalism” or “humble minimalism” by Brazilian artist Cildo Meireles. Standing alone at the center of a dark room is a tiny wooden cube, so minuscule that a child managed to swallow it at a previous exhibition. Made of oak and pine, two types of wood that are used to make fire and thus sacred to the Tubi people of Brazil, the piece draws inspiration from the Southern Cross constellation. It not only invokes divinity through its allusion to the sacred, but refers directly to a constellation that was used as a guide by colonizers of Brazil. This duality is central to Meireles’ work, which he sought to minimize and reduce to the smallest size possible, just as the Jesuits reduced the Tubi cosmology down to practically nothing. A tiny remnant still remains, however, and the small wooden cube has the potential to become fire. This potential is not only reflective of the transformative power of nature, but that of art, and it is truly breathtaking to see the two go hand-in-hand throughout ‘much wider than a line’.