Through the interplay of flat surface and dimensional object, a thing and its representation, Dutch artist Rachel de Joode traces a line of inquiry around the nature of art and the interconnectedness of things. The temporality and ephemerality of matter is articulated in the hybridity of her photo-sculptural works, which engage the senses in an embodied interaction between nature and artifice. Abstracted, close-up photographs—surfaces that represent other surfaces—are composed into amorphous forms that are propped up on pedestals or protruding from walls. Through human and digital processes of integration and dematerialization, de Joode stages encounters that illuminate the experience of a connected existence that increasingly unfolds on screen.

Rachel de Joode: Sculpture in Pond, 2016, archival inkjet print on dibond // © Rachel de Joode

In a direct engagement with materials that reference traditional sculpture and its techniques—such as clay and marble—de Joode permits these to remain raw, as articulations of matter itself. The disintegrative processes of digital photography lead to the re-emergence of such physical objects in a new state, altering our relationship to the things around us. Through recorded, though re-contextualized, traces left in materials and collected from the human body, de Joode stimulates awareness of the continual and interactive processes of time and transformation: manifesting the state of being in between.

Julianne Cordray: Your background is in time-based art. How did the exploration of this potential evolve through sculpture?

Rachel de Joode: Time-based art is basically every art, if you think about it. I graduated with photography and two short films. I thought I would make more short films, but I realized that you’re not independent when working with film. The fun thing about making films is the set and staging, so it just felt really natural to continue with photography in the same way. Then I started making a lot of still lifes: photographing objects and arranging them, and thinking about the semiotics of objects. It made a lot of sense at one point to just not photograph them anymore and leave them be. That also had a lot to do with this idea that if you stage things in a gallery space, it ends up as a photograph anyway, since most art is consumed on the internet. It’s this constant play between the real object and the photographic representation of the object. We live in this flat world already, a screen world. The photograph is not the object, but on the other hand it is. I like the idea that even the representation is the same thing as the object; it’s just a different form.

Rachel de Joode: Detail // © Rachel de Joode

J: Skin has a particular presence in your work—manifesting in representations of actual skin as well as materials, textures and tones that resemble it. Can you talk about your interest in skin as material and subject?

RdJ: Our bodies have so many bacteria cells, or foreign cells, that human cells are outnumbered. One out of ten cells in the body is human and the rest are just something else. We’re sort of a landscape for everything. And it’s so weird that we’re not even human, in that sense, if only the minority of cells are human. I’m interested in this idea of being porous—we’re breathing and dust particles get into our bodies and we release things into the world—and constantly living on earth together with all these materials, both organic and inorganic. And I think that process is also reflected in the skin, because it flakes off. It’s so small that we don’t see it, but our skin is probably everywhere around us. There’s this porous back-and-forth between everything around us and us, which is happening on our surface. That’s the only part we see. We leave traces, and traces are left on us. It’s this constant back-and-forth that I find really interesting about the skin. And it’s in flux. It’s always changing.

JC: Because of the close-up, cropped and abstracted nature of the surfaces that compose photo-sculptures, the images become so textured that you are drawn to their materiality in a tactile way, while at the same time there is something repellent about them. It seems to challenge, and also interweave, the senses of sight and touch.

RdJ: I think that has to do with the way our eyes see things versus the way a camera lens sees or captures things. I recently rented this 50 million-pixel camera for a project I am working on and currently making tests for. The interesting thing was that it became scientific because it’s so sharp and microscopic that it changes your perception of objects. I think that also makes objects repulsive. Our eyes are making everything nice for us so that they’re more manageable. If we could see more detail it would just be too much information. There’s much more than even the lens can see, and also so much less. It’s just a way of looking at things. But I think this sense of being attracted and repulsed at the same time is something I search for. I think I want people to have these emotions. I think I want to have these emotions when I make the work. These weird, very primordial emotions you can experience just from matter. It’s hard to put that into words because it’s more like a feeling that you get through looking.

Rachel de Joode: ‘Not Touching A Meteorite’, 2013 // © Rachel de Joode

JC: There’s a photograph, ‘Not Touching A Meteorite’, that seems to illustrate this tension between being compelled to touch something but also resisting.

RdJ: That work came about by accident. I was doing a residency in Frankfurt and I was planning to do a project with a meteorite. A curator of the meteorite collection there was always showing me these meteorites with her hands—without gloves or anything. I wanted to photograph them in my hands, but when I went there on the day of the shoot, she said that I could not touch them. That was exactly the idea, because I wanted skin contact. So that work ended up very different. I was really trying not to touch them. It was the closest I could get with my finger. Then there’s this sort of space in between my finger and the meteorite. I think it’s more about that empty space.

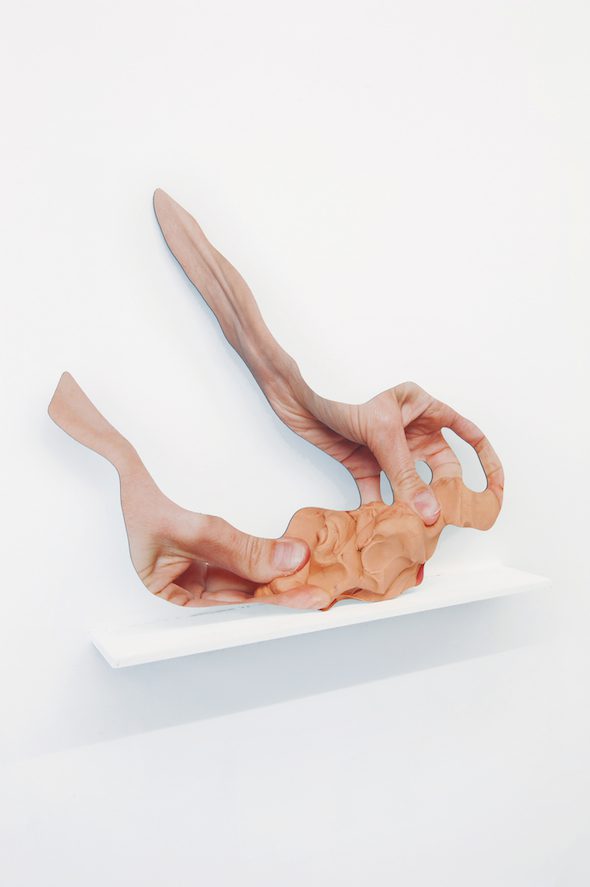

JC: There are several photos of hands touching and interacting with the materials that you work with, such as clay. Is this intended as a reference to your own working process—almost performative in a sense—or as a personal engagement with material?

RdJ: I like materials that refer to art. Clay, marble, or bronze—those sorts of iconographic materials. I think it’s weird to make the decision to be an artist. And then there are these materials in the world, like marble, which never asked to be representative materials of art. I like the sort of comic aspect of those materials. You don’t really have to do anything with them, because it’s enough. I get some clay from the art supply store and I just handle it: leave traces of me, of the artist. It’s just the clay and me, and we make an artwork together. So, it’s more of a conversation between clay and me. And that’s what I photograph.

Rachel de Joode: ‘Across Fingers Clay’, 2015, archival inkjet print on dibond // © Rachel de Joode

JC: Are there any new materials you’re working with now, or that you’re planning to experiment with in your photo-sculptures?

RdJ: I’m making pictures that are getting a bit more liquid. I started taking photographs of clay and I was really into the parts where it’s still in the plastic bag. So I got really into plastic. I’m also researching printing on glass, which is also reflective. That’s an area I’m exploring. But it’s in an embryonic stage. That’s something I’m working on for the upcoming show in Oslo at the Henie Onstad Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art. How it will evolve is something I’m curious about myself.

Rachel de Joode: ‘(makes squish gesture) IV’, 2015, painted carved foam // © Rachel de Joode

JC: You’re also participating in the Cycle Music and Art Festival in Iceland this fall. Are you working on anything new for that?

RdJ: Yes, I’m making costumes. And they’re actually for a video, so I’m back in the world of moving images. It’s basically flat surfaces that are wearable: installed on a human, let’s put it like that. I’m bringing the two together again—the artwork and the human—and also the human thing and the art thing. And I also like this idea of humans pretending to be materials. Or maybe materials pretending to be human, in a way. That’s what I’m working on at the moment.