Article by Louisa Elderton in Berlin // Wednesday, Sep. 07, 2016

You could say that Erwin Wurm goes that extra mile to make people work. I mean, really work. At his recent Berlinische Galerie exhibition, the main hall buzzed with frenetic energy as crowds of people climbed onto plinths to perform Wurm’s ‘One Minute Sculptures’ (1995-present). These blur the boundaries between sculpture, object and performance. Following his instructive drawings, men, women and children lay down upon oranges, their bodies levitated by the globes of fruit; books were stiffly stacked between arms and legs in a desperate attempt not to let pages flutter to the ground; two people at a time burrowed inside a jumper, wool stretching at the seams as both heads popped out of the top, individuals reborn as Siamese twins. Hold for one minute, aaand release.

Born in Austria (1954), where he continues to live and work between Vienna and Limberg, Wurm’s practice is concerned with the sculptural aspects of daily life, often bending banal everyday elements into something entirely new: cars assume obese proportions, rolls of fat bulging as metal; or houses are compressed to a width of 1.10 metres, walls closing in around you. We spoke to Wurm about his propensity for twisting reality and just what the future might look like. The artist will be showing at this year’s abc—art berlin contemporary for König Galerie.

Erwin Wurm, Portrait // Photo by Ingo Prader

Louisa Elderton: There is often an interaction between people and objects in your work. Why do you implicate the human body and make the viewer work in this way?

Erwin Wurm: This happened slowly. When I started to work as an artist, I asked questions about sculptural notions: two-dimensions, three-dimensions, mass, volume, surface, skin, time. Slowly, I realised my pieces had a short lifespan, that they were very specifically time-based; there was a beginning but also an end. Even in the past, artists like Michelangelo wanted to be able to roll a sculpture down a mountain and still have it existing in 500 years. So time has always been important to every art piece. I was interested in shortening it, because in our society—our time-consuming society—we throw things away. Nothing exists for long and objects have a short life. I realised that by doing something that exists only for a short period of time, I would have to either travel to install works myself or send instructional drawings. The ‘One Minute Sculptures’ deal with two aspects; the first part is time, and the second part is an instruction where someone else follows this to realise the piece.

LE: So your interest lies less in the body per se and more in time and how it implicates people?

EW: You’re right, but I work on the whole entity. The human body does not only mean the physical body, but also the psychological and spiritual and many other layers. Even the house is a part of our body: it protects. We have skin, the second layer is our clothes and the third layer is the house or car, which protects. These are all part of the human entity.

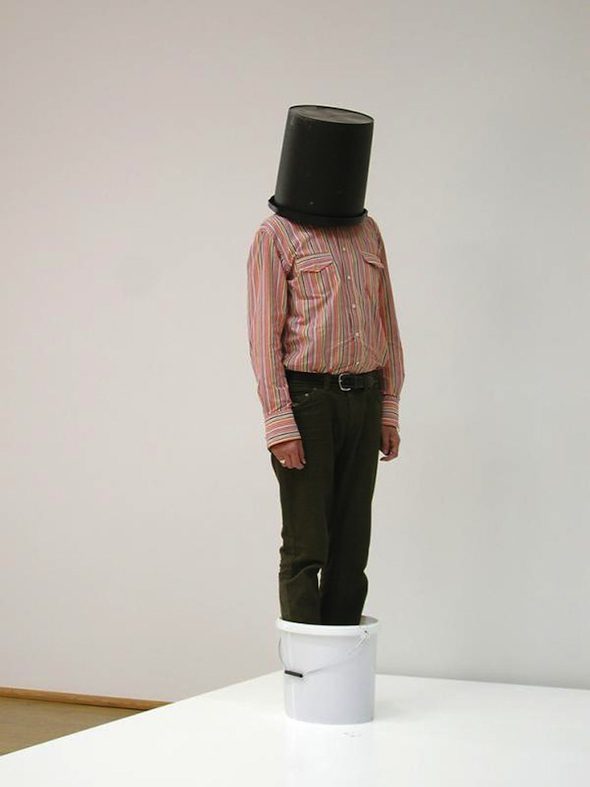

Erwin Wurm: ‘2 Buckets, One Minute’, 1998/2016 // Courtesy of the artist and König Galerie

LE: By destabilising elements that might normally protect us (playing with the scale and size of houses, cars etc.), do you make the viewer vulnerable?

EW: It’s part of exploring the psychology of how we function. I ask questions about these issues. The ‘Narrow House’ was actually my parent’s house. I was invited to make a show at the Ullens Centre for Contemporary Art. I saw this gigantic museum and was annoyed to only have this narrow space. At first I thought, I just won’t do the show, but then I thought I’d address my anger by doing a narrow piece.

LE: So your work often results from circumstance?

EW: Quite often it’s the result of a personal or professional disaster.

LE: How might this subvert the historical idea of the artist as genius?

EW: Gerhard Richter once said that the paintings are smarter than him. Once you accept that, it leads you in a certain way. Some artists have a strict idea and they follow it, whatever happens. Others have an idea, but circumstances change that. I’m the second kind of guy. My first question is always: how can I realise this idea? Do I have to make a photograph, a performative sculpture, a text, a video or a three-dimensional sculpture? What fits best?

Erwin Wurm – ‘Curry Bus’, 2015, Bus, styrofoam, polyurethane, 220 x 250 x 550 cm // Courtesy of the artist and König Galerie

LE: Are ideas the core of your work, the material realisation being secondary?

EW: Not at all. I think it’s the way an art piece is made that that makes a good work or not. Many people have ideas, but how the idea comes to be realised, that makes the art.

LE: In your recent exhibition at the Berlinische Galerie you say: “Whether we seek to master life with the help of a specific diet or a certain philosophical attitude, we all fail in the end.” How so?

EW: In life and in death, we all have to correct ideas of who we are and what we want to be. We all have illusions at the beginning, and as life progresses we realise that reality is different. In the end, we all fail because we’re all going to die. Certain philosophers and artists create bodies of work; you think you’ve reached a certain point coming close to a social reality, and then you realise that the next generation thinks differently, that your ideas are old fashioned. That’s also a failing: we have a certain moment and then, that’s it.

LE: Does the humour in your work lighten this bleak existential condition?

EW: Well, I’m not a joke-teller. I look at my time and society. I want to reproduce certain effects related to daily life—the questions in our society. We all want to be forever young, look good, be smart, successful. This stands in relation to reality. When I made the first fat car, people laughed. But it wasn’t all that funny. It’s a car which has a certain obesity, I combined the biological system (of growing) with the technological system of constructing an engine; when you connect these things all of a sudden it becomes interesting because a car can grow fat, or a house can become slim. It relates to human beings. I relate sculptural questions with social issues. I try to look for the possibility of sculptural aspects in our daily life or world. I can then twist reality—and the most banal things—into something else.

Erwin Wurm – ‘Cucumber’, 2010, bronze, 167 x 42 x 50 cm // Courtesy of the artist and König Galerie

LE: Do you want to shift the viewer’s perspective?

EW: No, I’m very self-centred when I work. When I make the performances, it is an imperative that you are invited to follow my instructions. If you do something else it’s okay, but it’s not a piece of mine.

Erwin Wurm: ‘Disorder’, 2016, acrylic, fabric // Courtesy of the artist and König Galerie

LE: In terms of future generations thinking differently, how might people react to your works in 100 years?

EW: I have no idea. What counts for me is today and now.

LE: So longevity is of no interest to you?

EW: Sometimes I make up games with my friends and we say: where would you go if in a time machine? Many people say they would visit their parents when they were young. I would like to go a thousand or a million years into the future. That would be exciting. Imagine what happened in the twentieth century alone; forty years ago we had no internet. I’m pretty sure that machines and technology will develop so far that very soon parts of our bodies will be machines and computers. That’s exciting and would be very interesting to see.

Exhibition

ABC – ART BERLIN CONTEMPORARY

König Galerie: Erwin Wurm

Art Fair: Sep. 15–18, 2016

Station-Berlin, click here for map