Every era has its quirks, its paranoia, its fears, its diseases, its corrupt politics, its hopes and dreams. Bundle up all these currents and you have a Golem. As the origin myth goes: in the 1600s, in Prague, Rabbi Löw fashioned with his bare-hands a humanoid creature out of clay. Then, he inserted the Shem—a scroll with mystic Hebrew letters—under its tongue, thereby breathing life into its being. Perhaps the most well-known of Jewish folklore, a story with many versions and permutations, the notion of the Golem is timeless. From now to January 2017, the Jewish Museum Berlin pays tribute to this iconic figure, spanning 600 years and 250 works of art, artifacts, video games, and even a FaceRig. The Golem is a symbol for past and contemporary times, for projection, for destruction, for processes of creation, and for innovative technological advancement; in short, a zeitgeist.

Paul Wegener’s Golem as a FaceRig, Installation view at Jewish Museum Berlin, 2016 // Photo by Nina Prader

On the premise that every era creates its own Golem, Trump’s election propaganda—a baseball cap branded with “Make America Great Again”— is on display. The looming threat that Trump could become President of the United States shapes a present and a possible future. This prognosis and chapter in American history—apart from catalyzing a sense of foreboding—calls for a Golem, a saviour.

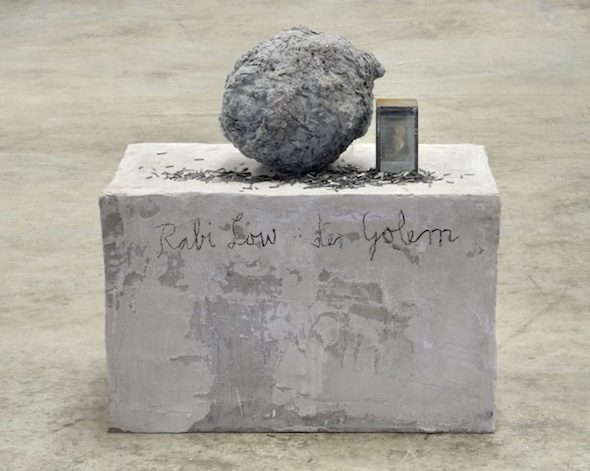

Physical representations of this creature as sculptures, action figures, or as puppets are exhibited. Amsel Kiefer’s visceral cement mound, like a giant fossilized ostrich egg, illustrates the Golem as a vision. In this heavy, monumental state, the matter seems to pulsate, reminiscent of an embryo. At this stage of projected animism, the Golem is pre-formation and pre-transformation. It is pure, raw idea without contour, before Rabbi Löw sculpted its shape. This is where the integral question of the Golem rests: the act of creation is an artistic one but also signifies the hubris of humankind. To try to imitate life is to copy God’s work, or so the scripture goes. In Jewish mysticism, however, the process of making is more important than the reason; bringing static matter to life is a kind of worship.

Anselm Kiefer: ‘Rabbi Löw: der Golem’, 1988-2012, in the exhibition GOLEM at the Jewish Museum Berlin // Courtesy of the Jewish Museum Berlin

Essentially a type of avatar or Doppelgänger, the Golem possesses no will or ego of its own, but is controlled by the Rabbi. In this way, it is also representative of technological advancement and innovation, ranging from robots, computers and weapons to iPhones. Aptly, the first Israeli computer switchboard in 1965 was dubbed a ‘Golem Aleph’. The fear directed at Artificial Intelligence can also be read as a source of empowerment. On one hand, an aid to human kind; on the other, risky, for it may become autonomous or is fallible, based on its human wielder. In part two of the story, the Golem is at first an obedient machine and companion, doing the Rabbi’s bidding. However, one day, Löw forgets to remove the life-giving scroll from the Golem’s mouth on the Sabbath, and the Golem goes berserk, unleashing havoc and destruction on Prague. In this version, the Golem is somewhere between an action hero and a demon. No wonder, Marvel comics used the story in an episode, “The Incredible Hulk: In the Shadow of the Golem”. However, the Golem as a Jewish destroyer figure has run the risk of promoting anti-semitic thought in pop-culture.

In addition to cinematic representations of the Golem with a Prince Valiant hair-cut, most famously by horror film director Paul Wegener, its look takes on many forms and philosophies. Christian Boltanski’s memory-inspired work sheds a more ephemeral light. His Golem piece is powered by a tiny motor and backlit by a flashlight, a shadow of a monster’s face creates a caricature on the wall, reminiscent of the parable of Plato’s cave. The cast shadow is as close as humans get to understanding reality.

Daniel Laufer: ‘Redux’, 2014, Installation view in the exhibition GOLEM at the Jewish Museum Berlin // Courtesy of the artist

Changing the dialogue, Berlin-based contemporary artist Daniel Laufer’s 7-part installation transports the viewer out of the museum context and into a gallery-like setting. Laufer’s works, including ‘Schüfftan’s Mirror’—named after a special effect used in the movie Metropolis—, a painting of the ‘House of Golem’, and a video piece titled ‘Redux’, are in conversation and refract onto each other. From every angle of the room, the pieces mirror: truth awakens the Golem and the honest looking-glass is a visual truth-telling device. Laufer doctored these reflectors, adding information and blind spots. Scratched out marks cast little anamorphic shadows onto the ground. Are they Golems? Tiny illustrations are imbedded into the mirror-pieces. The ‘Lantern of Prague’ shows a technical drawing of the first laterna magica. Though Rabbi Löw was credited as having created the Golem, it is rumored he also invented this machine, a prototypical projector, at the court of Rudolph the Second. This leads to the question: was the Golem story woven around this technology?

Laufer’s work takes the notion beyond metaphoric representation. In his video work, the Golem is framed as an unseen apparition, remaining a myth. Linking to World War II history, he researched Jewish refugees, who hid in graves at the Jewish Cemetery Weissensee, which was miraculously left untouched during the war. One survivor credited ‘the cemetery Golem’ for living through those dire times. This adds a layer to the Golem’s personality as a friendly ghost and protector of its people, only going crazy in a time of persecution and plague. In this way, the Golem is not only a threat but also a mirroring shield.

As a whole, the Jewish Museum’s exhibition paints a multi-faceted and holistic picture of the Golem, focusing on its history, origins, and contemporary excavations. Oscillating between the past and the present, the hysteria surrounding the conscience of the Golem receives a will of its own and, ultimately, sets up the integral and relentless take-home message: what does it mean to be human?

Detail from The Lantern of Prague, Installation view in the exhibition GOLEM at the Jewish Museum Berlin // Photo by Nina Prader

Exhibition

JEWISH MUSEUM BERLIN

Group Show: ‘Golem’

Exhibition: Sep. 23, 2016–Jan. 29, 2017

Lindenstraße 9–14, 10969 Berlin, click here for map