Berlin is brimming with transient artists. Originally from Uruguay, Madrid-based artist Veronika Marquez was a resident at Institut für alles Mögliche in Wedding for the past three months. We sat down in her temporary live-work-studio to talk about the behind-the-scenes of her conceptual photography.

There were various wigs on the bed. One was a frumpy Cleopatra-cut, the other coiled into long, raven-colored locks. Veronika showed me her props for her performative photography sets. These comprise the costumed identities that go into her personal explorations and documentations, working through the memories from when she worked as a sex worker. Nowadays, she separates herself from the lives she lived, but takes them with her, performs them as stills or moving images against white backdrops and scenic landscapes, positioning them as iconic female archetypes in and out of everyday private and public contexts.

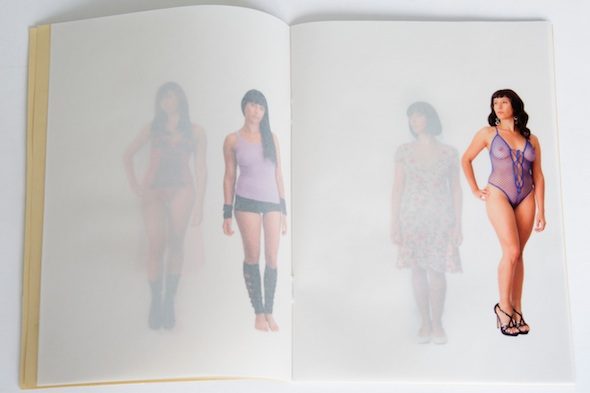

Veronika Marquze: ‘The Last Supper of Veronika Marquez’, Zine-catalogue from the performance // Courtesy of the artist

She handed me a booklet made out of translucent pink paper. Every page showed the same woman dressed in a different outfit. From fetish dominatrix to girl-next-door in floral prints, they are all portraits of Veronika. But are they really her? On each page, in each photograph she looks like another female figure, another space to project identity. Who is she? Who is she no longer? Her portraits courageously share aspects of her story.

Nina Prader: Tell me about Camila and how she translates into your art practice? Is she an alter ego, a persona, pseudonym, character, friend, or a memory?

Veronika Marquez: Camila was a part of my life but now she has her own life.

I tried to use the residency space as an empty space, as a space of identity. In my art work, I use characters. Now the characters are more defined than in different times of my life.

This is Camila. She is a prostitute, but a luxury woman. I don’t show sex in my art work. I work with the body. Camila is never fully naked. She came from Latin America but this is more of a European conversion that I tried to be. This is me now.

[Veronika points to the woman wearing a purple fishnet leotard and black curls, then to the woman with a bob, then to the woman with blue hair and overalls, sitting like a queen on her throne in the middle.]

Veronika Marquez: ‘Camila, Veronika & Veronica’, Berlin 2016 // Courtesy of the artist

Sometimes Camila questions me. Back then, I did not plan for the future. I really liked not knowing what would happen today or tonight. I was sometimes in unsafe situations. Now, I apply for artist residencies, I plan for the next two years. Sometimes, I miss the past and feeling the risk in life.

NP: We move for emotional or economic reasons. You travel for your art work. When I see your portraits of Camila, I think it is more complex than showing a type of woman. Camila is your travel companion. She comes with you on your trips to residencies. Could you talk a little bit about Camila’s friend? Does her polar opposite have a name too?

VM: Not really. At first, I named her after myself but adjusted Veronika to be written with a “c”. This is the difference I put between these two. I don’t find it so strange that they are friends. In real life, opposites can be friends.

When I prepare for my photo-shoots, I imagine the dialogue. I need to know what Camilla is doing and what Veronica is doing. Rather than talking, they are spending time, doing natural things like eating a chorizo. When I travel, I try to use the place where I live; I spend more time inside.

Now, I see myself as the producer. I play with the production role: I construct landscapes and characters. I am somebody who is neutral. I make these characters but they are related to my life. It’s stupid how something so simple as hair can make such a difference, culturally. For example, when I shaved my head: in Uruguay, people labeled me a hippie or thought I was the police; in London, people looked at me like a skinhead; and here, in Berlin, it’s maybe considered cool. Now, with my blue hair, people think I am funny and friendly.

Veronika Marquez: ‘Camila & Veronica eating chorizo’ from the series Montevideo // Courtesy of the artist

NP: You use your body as a tool in your work to open up conversations but you also set up boundaries with, for example, the wigs. How do you stay in control?

VM: It’s a natural process. They define different periods of my life. It’s like a human time-line. A curator once said to me: “It’s like you have an agency of models.” I train for my work, for example, taking pole-dancing classes. I work with choreography. What characters can I take? What movements can I make? Which movements belong to Camila? I use sensual things for my work but I think all my characters have their own sexuality.

NP: Is Camila political?

VM: She is not involved in politician-type things but she knows a lot of politicians in her work. [laughs] She is in a difficult situation. Some feminists don’t agree with this kind of work. When I show this art work, they ask, “Are you a feminist or not?” Now, I am more relaxed about this question but before I didn’t want to name myself a feminist. If I said, “I am a feminist”, they took my work; if I said no, they did not. I don’t like this kind of question. “I believe in the power of women,” is my answer, when I defend Camila. It’s not that she chose that path because she believed in feminism. That is not true. For me, it was a life.

In a political way, she and I use our bodies for ourselves. You can see this attitude as feminist politics. Sometimes women tell me that I only show the best and glamorous parts of prostitution. Through Camila, I encounter the past and the present for the first time. I see all the good things: this profession helped me a lot and I am proud of it. Then, in my performance ‘The Last supper of Veronika Marquez’, I researched the past, I read letters and I reconnected to those years. The performance was a raw reality of that time.

NP: Are there similarities between art-work and escort work?

VM: “Escort” is too glamorous a word. I think prostitution is more clear. You are very clear about the pay and the work you need to do. You have to speak clearly and be direct. But in art, you need to know how the city works. A lot of artists sell themselves too. Both are spaces of fantasy. But for sure, prostitution has better working conditions.

NP: You’ve shown your art work in Latin America and Berlin. What does migration mean to you?

A friend asked me: “what do you think about migration in your country?” Because he imagined there is migration there. There is no immigration in my country, nobody wants to go there, although it’s beautiful. There’s only emigration. I am an example. When you are in Uruguay, you grow up with the idea that you have to leave your country. You have two options: stay or go. People want to go to the USA or Europe for money, education, or a better life.

I felt connected to France. I was drawn to their culture and tradition of theater. In Europe, there is a lot of privilege. But even if there is a lot of privilege, life is not necessarily the best, or the weather is bad. Camila comes from this background. She tried to leave her country for a better life, but never found it. She went to Buenos Aires and came back again with me to Montevideo as an artist-in-resident.

Veronika Marquez: ‘The Last Supper of Veronika Marquez’ // Courtesy of the artist