Speech is perhaps the most direct form of communication available to the human race. By selectively using words that have been sourced from a vast vocabulary, any given person is able to express their thoughts and feelings without hindrance. Or so goes the theory. Of course, we know that language, even when reformulated into your own words, does not always perform its intended meaning and, as soon as it leaves your lips, takes on a life of its own. It is for this reason that speech is a powerful tool within art.

Speech, or the ability to speak in a particular language, becomes a necessity for those who have been displaced from their homes and find themselves in unfamiliar territory. Art, in this way, may provide an alternative means to allow those, who are otherwise so easily misunderstood, to express themselves. Speech can thus be implemented in the art work with the underlying objective of giving the rising number of migrants, who have braved the treacherous journey from their homeland, a voice. And much like any creative device, it can be applied in different ways.

Set to the verses of W.H. Auden’s 1939 eponymous poem, the documentary short ‘Refugee Blues’ (screened at Interfilm this year) depicts the harsh reality of life in the refugee camp outside Calais. With the incorporation of oriental song and wide, panning shots the frequent clashing of the French riot police with the inhabitants of the camp is shown with compositional grace. The poem is recited by a refugee so that the words, once written by a poet in response to the diaspora of World War II, are now spoken by a representative of the crisis of our times. Directors Stephan Bookas and Tristan Daws hereby connect the present with the past, forging links across history. ‘Refugee Blues’ achieves a sensitive, melancholic tone and the use of speech effectively acts as a testimony to the gravity of the current situation.

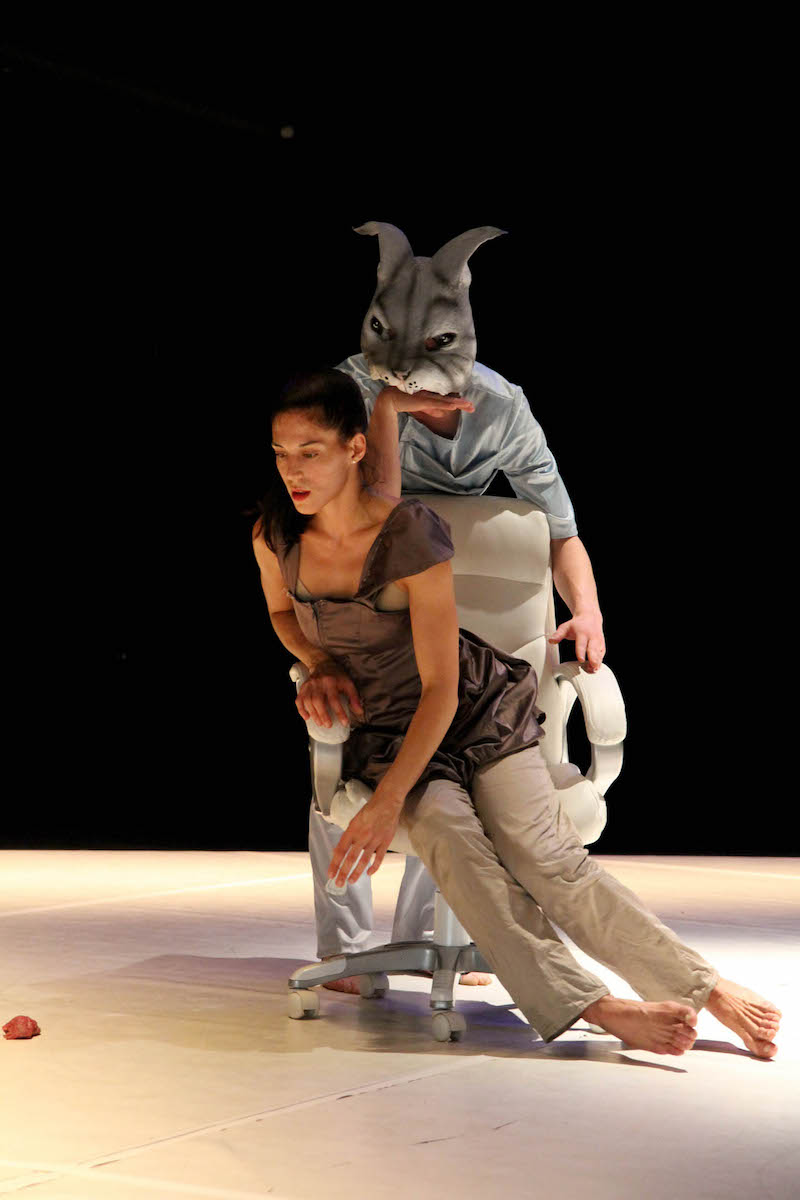

The dance trilogy ‘DisPLACING Future’ by choreographer Helga Letonja—performed at around the same time in Berlin—tackled a similar theme: through movement, the piece reflected on displacement in our diverse, multicultural society. The third part, presented at Halle Tanzbühne, dealt with the uncertain state many experience upon reaching unknown shores. Performers in zebra costumes and rubber rabbit masks questioned notions of identity and anonymity, displaying their anxiety through the physicality of their bodies. Undoubtedly influenced by Pina Bausch’s distinct style of Tanztheater, each dancer fought with themselves and each other in emotively driven movement sequences. Whether caught in golden gloves or teetering precariously on top of a single high heel, a virtuosic struggle underscored each episode and brought the piece together as a coherent whole. Due to the masks, the performers often could not resort to facial expressions to tell their stories, which resulted in the development of a strong movement language. In this way, their vocabulary was outlined by the fine-tuned dynamics of their performance, as they engaged with one another in a nuanced movement conversation.

Alongside speaking with their bodies, the dancers spoke in their native languages. With the piece focusing on migration, it is not surprising that Letonja chose to incorporate monologues in tribal African languages and in Arabic. But the beauty of the unfamiliar sounds was spoilt with the on-the-spot translation into English, as the meaning of their words became all too literal. Their struggles, which they had just expressed so strongly in movement, were transformed into a lecture on injustice and morality. Instead of fortifying their message, this melancholic sermon took away from the dancers’ established mode of communication and did not reach the height of expression that the rest of the piece so firmly possessed.

In two very different ways, Bookas, Daws and Letonja used speech in film and stage performance respectively. Both pieces succeed in provoking questions in terms of the need for speech, especially in regards to speaking the same language. But do we need to understand one another’s words in order to understand one another’s pain? Is an explanation required in order for empathy to be inspired? Perhaps giving someone a voice does not mean resorting to the most obvious, literal mode of communication in internationally recognised languages. Instead, maybe it is the viewers’ task to meet the artist half-way and find alternative modes of understanding.

Additional Info

facebook.com/refugeebluesfilm

halle-tanz-berlin.de/en/works/the-desert