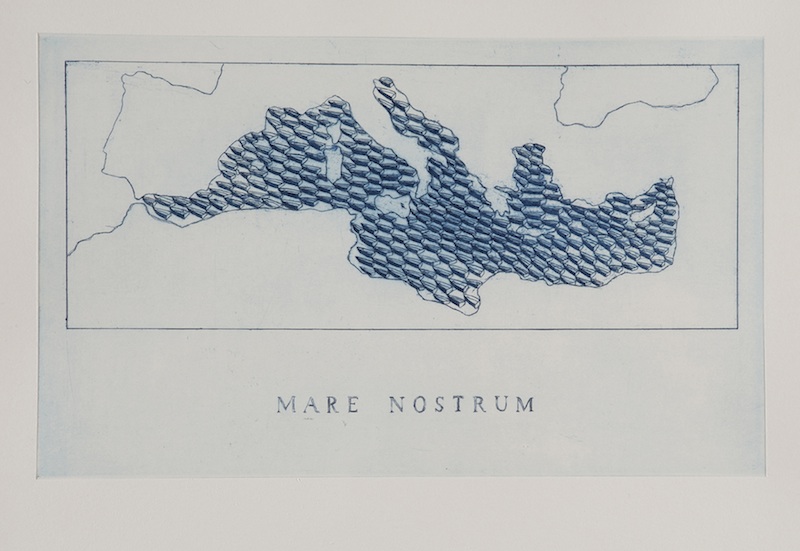

I first encountered the work of Belgian-born Philip Aguirre y Otegui at this year’s Ireland Biennial, EVA International, where I was struck by his new installation ‘Cabinet Mare Nostrum’. Monotone blue, coffin-shaped boats were painted upon the wall, a mass grave echoing the shape of the Mediterranean Sea. Within the same room, a painting portrayed an ornate bridge crossing the Mare Nostrum, underlining the mass movement of people from Africa and the Middle East; also depicted were silhouettes of humans trapped behind wire fences, portraits of a world in crisis. And in crisis we are: over the space of six months Trump has become President-elect of the United States of America and the EU referendum in the UK led to Brexit, amidst a refugee crisis that has forcibly displaced countless people worldwide.

Aguirre y Otegui’s work often reflects this profound sense of human tragedy, representing conflicts linked to migration, from the genocide in Rwanda to the present day crisis in Syria. We discussed his views on the recent breakdown of democratic and human values, and the right-wing political agendas that feed off of fear, rather than providing perspectives of hope.

Philip Aguirre y Otegui: ‘Mare Nostrum’, 2016, etching // Photo by Koen de Waal, courtesy of the artist

Louisa Elderton: Your work ‘Cabinet Mare Nostrum’ (Cabinet of the Mediterranean Sea) focuses on contemporary migrations and your work is often concerned with refugees. What do you think the role of the artist is—or can be—during these times?

Philip Aguirre y Otegui: Since the genocide in Rwanda in 1994, the issue of refugees is very present in my work. At that moment, I really had the feeling and conviction that I had to communicate this theme in my artworks.

As a child, I grew up with a lot of stories about refugees, stories from the Spanish Civil War and WWII. This certainly had an impact on me and made me very sensitive to the problems of refugees. I made works about the flow of refugees in Rwanda, but also about the boat people who travelled from Morocco to Andalusia in Spain, and the huge illegal migration by sea from Senegal to the Canary Islands. It’s a phenomenon that spans time and, unfortunately, it will happen again, many times over.

Sometimes it’s so cruel and incomprehensible. In 2002, I made a short movie about the situation of the refugees in Calais, France. Now, in 2016, the situation is much worse. They removed the refugee camp (the “Jungle”), but in fact there is no solution at all. For me, as an artist, it’s important to use my work and the public forum (debates, press, lectures etc.), to talk about the refugees and to highlight the need for solidarity. But this is my own position as an artist, and not something you can generalise for all artists.

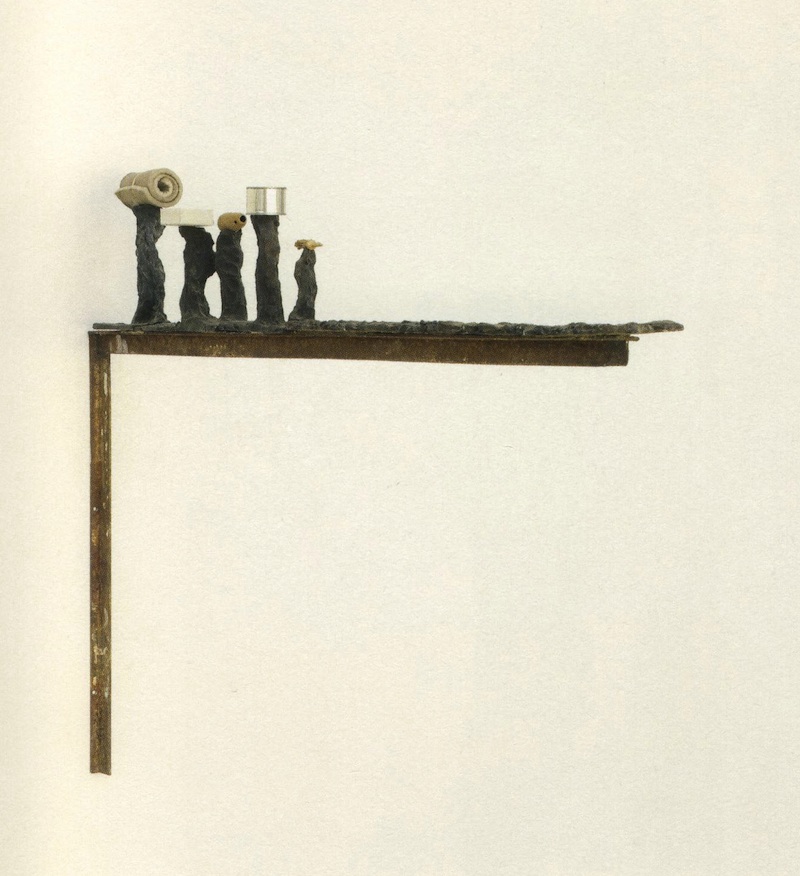

Philip Aguirre y Otegui: ‘Still (the) Barbarians’, 2016, installation view at Hunt Museum // Photo by Koen de Waal, courtesy of the artist

LE: What was your approach with the work you presented at the Hunt Museum for Ireland’s EVA International biennial of contemporary art, titled ‘Still (the) Barbarians’, which was almost like a cabinet of curiosity of small figurine sculptures and related drawings?

PAO: In my studio I have a lot of vitrines and shelves containing small sketches for sculptures, strange objects, and curiosities that I have collected while travelling. These include bronze sculptures and terracotta objects. By placing these objects next to each other, you unconsciously create new stories and associations.

Koyo Kouoh, curator of ‘Still (the) Barbarians’, knows my studio well and she immediately saw the link between these and the rooms of the Hunt Museum. The Hunt Museum collection includes Irish artefacts, Egyptian and Roman antiquities and art objects, and this is all presented in a bourgeois setting with a lot of vitrines.

Koyo suggested the jewelry room as presentation room for my work. It’s like the treasure house of the museum. I liked the idea immediately. In this almost sacred room with built-in cabinets, I created a story with sculptures, assemblages and small paintings, all selected from my studio. A mini universe arose by entering into this space, creating new combinations of my work. For example, a painting about Coca-Cola that I made in Ecuador was in confrontation with small sculptures referring to Belgium’s colonial past. My work integrated perfectly and fluently in to this historical collection of the Hunt Museum, and this integration made it beautiful, surprising, and even confusing for the public.

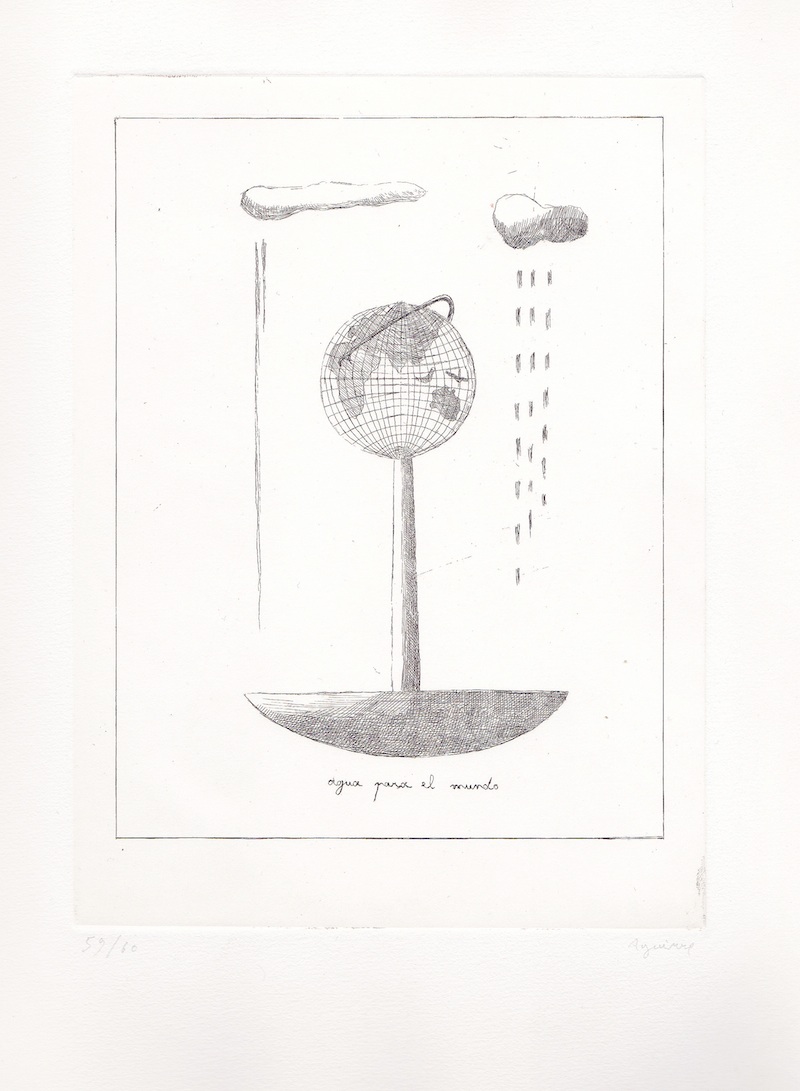

Philip Aguirre y Otegui: ‘Agua para el mundo’, 1991, etching // Photo by Koen de Waal, courtesy of the artist

LE: As a subject, water recurs throughout your work. What interests you about representing and examining this important resource?

PAO: Indeed, water is a recurring theme through my work. It actually began around 1990. In my studio I was assembling a lot with all kinds of objects, especially with receptacles and tubes. So actually it started with a formal, aesthetic interest.

Just as Fernand Léger—who was fascinated by tubes, giving form to his ‘tubism’—I was fascinated by plates, calabashes, cans, and bottles. By working with these forms, there was a certain moment when I made the association with people who go and fetch water. At that moment I tried very consciously to depict the vital, social and political meaning of water in the world. You see this, for example, in my ‘utopian constructions’, which are constructions that intend to divide water in an honest and fair way in our world. Water becomes a symbol for solidarity, or equally, for oppression.

In 1991, I presented an exhibition with the theme ‘Agua para el mundo’ (water for the world). These were large sculptures, but also drawings and monumental etchings. The theme has continued to fascinate me, also because of my many travels through South America, Morocco and Africa more broadly. In all of these places, everyday life is determined by finding and collecting water from a well or a source.

In 2009-10 I was invited by doual’art, a non-profit centre for contemporary art in Cameroon, to participate in the triennial SUD (Salon Urbain de Douala). The theme was ‘Water in the City’, and in Douala, I found in the middle of a bidonville a source where every day more than 1000 families went to get their drinking water. I turned this well into a meeting place with a theatre. ‘Théâtre Source’ is a very monumental sculpture, 30 x 20 x 10 metres, within the centre of which is the optimized water source which is used day and night.

Philip Aguirre y Otegui: ‘Theatre Source’, concrete, Douala Cameroon // Photo by Koen de Waal, courtesy of the artist

LE: What is your opinion on the recent political developments in the world: Trump’s presidential success, Brexit?

PAO: What really worries me is the breakdown of democratic and human values, values for which people fought for so long. For centuries people have worked for democracy, for freedom and equality, for solidarity. This has resulted in societies where education, healthcare and culture are very important. Many of these values are now so easily put aside, and instead, they are promoting some sort of strange selfishness.

A lot of politicians confirm and feed the fears of many people, while you would expect from them, as leaders, to instead be providing new perspectives and hope. Angela Merkel is one of the very few leaders to remain very confident in the fight for the fundamental, human values of our society. She deserves a lot of respect.

Philip Aguirre y Otegui: ‘Exodus’, 1999, bronze and mixed media // Photo by Koen de Waal, courtesy of the artist

LE: Where are you next exhibiting and what are you currently working on?

PAO: I’m working on different sculptures to be positioned in public space: a monumental work for a square, another for a park, and one for a public building. At the same time, I’m working on a new solo exhibition that will be held in Antwerp in 2017.

In December 2017, a historical monument that I have made will be presented in Douala, Cameroon: it’s a monument to the Douala King, Rudolf Manga Bell, who was executed by the Germans in 1914. I’ve also been asked to be the curator of a museum show in mu.ZEE in Ostende, Belgium, about the work of the painter Felix Nussbaum.