How do we perceive the world as it changes around us, mediating the transition between before and after? How does this process bring with it new meaning, a new understanding of what came first?

The practice of Lebanese artist and filmmaker Ziad Antar navigates processes of change, from the socio-geographic effects of war and its destruction in Lebanon, to the rapid urban development of the coastline along the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and the shifting appearance of the city of Jeddah’s sculptures as they were veiled during renovations.

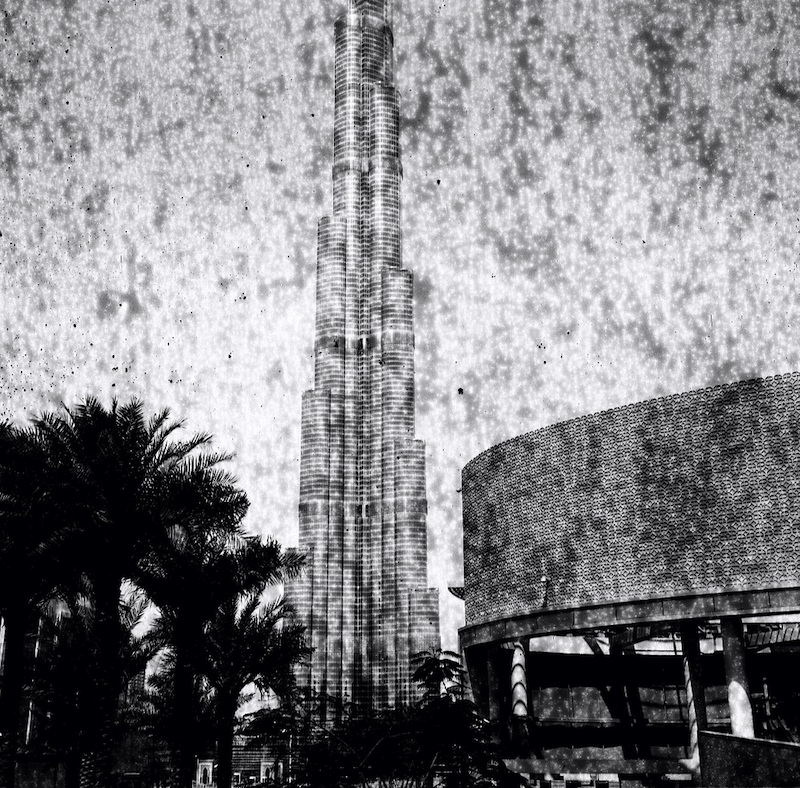

Palm trees rise into the sky, behind which the sea shimmers through the perforated, half-finished skeleton of an apartment block; Dubai’s towering skyscraper, the Burj Khalifa, slices through the center of a grainy black and white photograph, so marked it recalls stars falling from the sky to Earth; a sculpture is hidden beneath a sheet, its curvature and form nonetheless revealing itself. Compelling in their ability to both suspend time and reveal processes of evolution, the artist’s works raise questions about concepts of change, tradition and the notion of writing history.

Ziad Antar: ‘me and my house’, war series, August 2006, South Lebabnon // Courtesy of the artist

Louisa Elderton: Your work ‘Me and My House’ (2006) was produced after the Lebanon-Israel War, where you made a series about refugees in South Lebanon. What was your experience of meeting these refugees when taking their portraits; what did you learn about their experiences and how did you want to reflect this in your work?

Ziad Antar: When I started my photography and video practice in the early 2000s, I decided not to work on war and its archive as a direct subject. When the war started in 2006, I was in the south of Lebanon, in my hometown Sidon. The experience was a shock. My first reaction was to produce something about the war that was imposed on me; it invaded my city. I started registering the sounds of the war and filmed a little within my immediate environment — my house, my family. Very soon I decided to stop this work as I felt the need for some cold distance.

I felt the urge to document what was happening. What concerned me most in the first instance was the survival of the people. I documented refugees who squatted in schools, and survival food products such as tuna cans. I also documented vegetarian food cans left behind by the Israeli soldiers. At a later stage, I started a series of photographs with people posing for me in front of their destroyed houses. This series, ‘Me and My House’, was kind of a closure of the war for me. This process stopped with the end of the war. It was the first time I was working in a non-conceptual documentarian approach.

When the war ended I went back to working on the first images and sounds that I registered. My film ‘Safe Sounds’ (2006) reflected more my personal take on the war. It is also more consistent with my typical work approach.

Ziad Antar: ‘War Products: Tuna’, war series, Saida, 2006 // Courtesy of the artist

LE: Your practice has explored the idea of territory, especially in ‘Portrait of a Territory’ (2011). What interested you about photographing the UAE in particular, such a rapidly changing series of states?

ZA: What interested me in the UAE was the urban development along the coastline, reflecting the history of the port cities and their relationships to the sea. Traditionally, the UAE was a trading ‘counter’, then a pearl hub, and later a fisherman’s port. With the economic oil and gas boom, it was the sea in which they first invested and developed, either by covering it with concrete (in the case of man-made islands such as Palm Islands etc.) or by bringing the sea into the city. I decided to document these evolutions of the coastline by capturing the different elements that constitute it: architectural buildings, sand landscapes, frozen projects, trade goods, seaside walks, orchards, trees, empty villas, etc. Of course these images are not a straightforward documentation of how the coastline progressed, but rather, a take on this evolution that raises all sorts of questions in relation to concepts of change, tradition and the notion of writing history.

LE: ‘Beyrouth Bereft’ (2008) and the ‘Derivable Sculptures’ (2012) are arguably about showing monuments or places in a state of suspension or stalled transformation. Would you agree with that analysis or do you see them differently?

ZA: ‘Beirut Bereft’ is a photography project about unaccomplished, non-functional buildings that I see as forms, as sculptures and I photographed them as such. It is this suspended time that is interesting for me, a suspension that injects new meanings and hence new lives into these buildings. Whereas, ‘Derivable Sculptures’ is about extracting a veiled sculpture out of an image and giving it a concrete life. These were originally works of art that were commissioned by the mayor of Jeddah in the late 1970s and became a part of this city’s landscape—they became landmarks. They were veiled for the purpose of the renovation of the seaside of the city. I photographed these veiled sculptures and then produced the new sculptures based on the photographs. In this process, I was confronted with making sculpture for the first time in my career. In a way, there is a strong dialogue between the two works that questions the medium and perception of meanings.

Ziad Antar: ‘Axiom 2’, Jeddah 2012, B/W photography, Silver print 120×120 cm // Courtesy of the artist

Ziad Antar: ‘Derivable 02’, Jeddah 2014 Concrete sculpture // Courtesy of the artist

LE: How is the idea of conflict and change expressed in your work ‘Marche Turque’ (2006), where a pianist’s hands play a soundless piano, emphasizing its percussive aspect?

ZA: My approach in my videos works is to create a constraint while transforming an idea into a video work. What interested me in my video ‘La March Turque’ was how a small transformation in a device reveals new meanings. When I buffered the sound of the piano chords, you could only hear the percussion of the pianist’s fingers on the notes, reproducing the sound of an army march. Mozart wrote ‘La Marche Turque’ when the Ottoman Empire was at the doors of Europe.

LE: In your series of photographs ‘Expired’, what was it about the contrast of photographing contemporary subjects on old, expired film that interested you? Why this juxtaposition?

ZA: What interested me in this work is the magnification of the imagination. In the digital era you can see your image before physically producing it, whereas with analogue photography, the photographer has to imagine his image and consider all of the technical parameters and constraints. In my project ‘Expired’ I added yet another constraint which makes the outcome totally unpredictable. The process itself is a major element of the work. The series is one of those projects where its intricacies lie in the preservation story of the unexposed film rolls, bought at Studio Scheherazade from Hashim El Madani in Sidon. These 1976 expired rolls had survived flood, fire and rotting. It is the addition of all these constraints to my act of shooting the picture in 1999 that produced the idea/image. In parallel, this a project about time as opposed or in relation to timeless monuments or objects, it anticipates questions of the future in relation to the past.

Ziad Antar: ‘Expired’, Burj Khalifa // Courtesy of the artist