by Brit Seaton, studio photos by Ériver Hijano // Dec. 12, 2016

Christiane Dellbrügge and Ralf de Moll invite us into their minimal, office-like Mitte Wohnstudio—a space established for living and working. Finding the balance in these aspects of life characterises much of their artwork, which intersects somewhere between creative invention and practical solution. They seek and develop innovative systems, offering alternative realities and remedies to issues at the heart of society. These aims arise with a definite tangibility: Dellbrügge & de Moll focus on the next steps before we have reached them, presenting an experience we hadn’t yet realised was needed.

The studio appears neat and meticulously organised. Natural light floods through big window panes and a huge storage unit keeps the place tidy, reiterating that a clear space is a clear mind. A square desk sits as an island in the middle of the space, with a desktop Mac at the left of two opposite sides, resembling from above the yin-yang symbol as the duo work interdependently together. Everything is in balance and in sync: Dellbrügge & de Moll often say the same things at the same time. The desire to understand, solve and develop has influenced projects that show an acute awareness and reflection of the surrounding world and the people in it.

Understanding artist migration has provided much inspiration and material for Dellbrügge & de Moll, who recognise the significance of ‘place’ for an artist and their practice. Through conducting studies and interviews, they have collated a snapshot of migration fluxes and what it means to find somewhere different to settle and create. In their 2006 video project ‘Artist Migration Berlin,’ Dellbrügge & de Moll documented the stories of artists who had packed their bags with sights set on Berlin: the Emerald City of artistic opportunity. Interviewing 30 international artists revealed circumstances and success stories of moving to Berlin: it also put into perspective the reality of those who weren’t able to find exactly what they were looking for. De Moll joked about the desire in artists to achieve a stamp of ‘Berlin Approved.’ This, he explained, resonates on an international level, and sometimes results in an ‘art-drain’ in the countries left behind.

Unlike many of the interviewed artists who denied being an ‘insider of the Berlin art scene,’ Dellbrügge & de Moll have established a distinct platform for voicing the experiences and needs of artists. Another significant component of their work is the creation of art in public space, which denies the notion of borders. With developing community at the heart of their practice, it seems fitting that Dellbrügge & de Moll would also work with the future in mind. Their concept entitled ‘Camp of the Renegades’ envisions a settlement to which aging or ‘retired’ artists could migrate. The project was realised with the help of 30 artists over 65 years old, who contributed their idea of an ideal retirement settlement. The result was a commune formed with the consideration of self-sustainability, an economic system and most importantly, a new opportunity to fulfil the need to create.

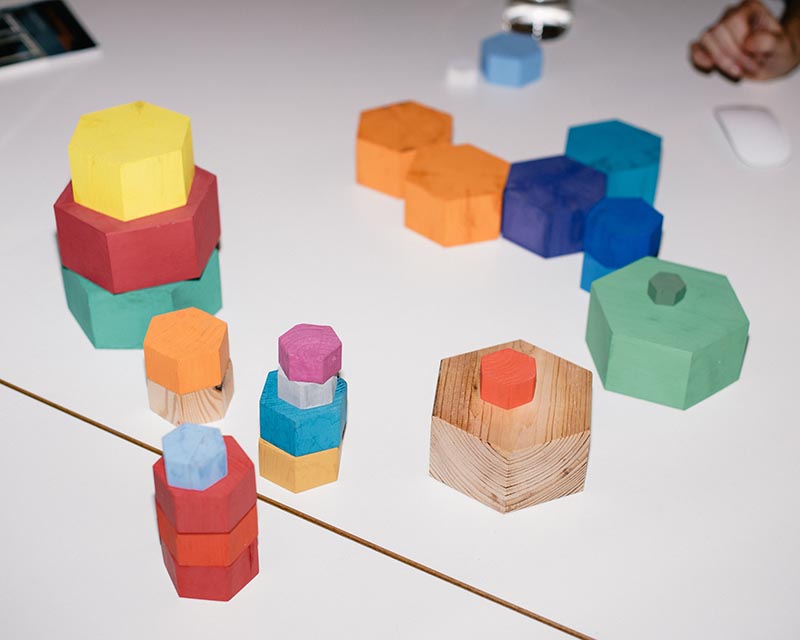

Set up on Tempelhof field in Berlin as part of The World Is Not Fair – The Great World Fair (2012), ‘Camp of the Renegades’ was constructed with hexagonal rooms, for easy expansion and structural stability. The honeycomb shape resonated as natural imagery, reminding of the organic desire to learn together, educate each other and continue with artistic practice. Dellbrügge & de Moll created a ‘Pavilion of Planning,’ with a table of hexagonal multi-coloured building blocks to plan the blueprints of the commune. The ‘Pavilion of References’ reiterated that the idea of an artist commune was not a new one: they displayed historical and contemporary examples such as Sun City in Arizona, Freetown Christiania in Copenhagen and Monte Verità in the Swiss canton of Ticino. They also included a performative element of two actresses, who in the role of the older artists who had been interviewed, interacted with visitors to demonstrate the potential reality ‘Camp of the Renegades’ could be.

During the visit, conversation often wandered back to the topic of Dellbrügge & de Moll’s previous studio in Dahlem, which now also takes form as a small white model on a workbench beside their desk. Originally constructed as The Arno Breker State Atelier, the building was once home to the creation of monumental works by the Nazi sculptor Arno Breker. Following numerous repurposes of the site during the post-war years, it became a studio house in the 1970s for international artists such as Dorothy Iannone, Ayse Erkmen, Jimmie Durham and Xu Tan. In recent years, the building was converted into a private museum by the foundation that supports the legacy of Bernhard Heiliger, Breker’s master student. In their 2015 project ‘The Monumental is my Malady’, Dellbrügge & de Moll criticise what they accept as a full-circle succession of the building’s ownership. The artist duo asserts this as a “politico-cultural scandal,” highlighting the complex relationship between art, politics and power.

Christiane Dellbrügge and Ralf de Moll know what it means to think as citizens of a wider world, where learning from history and the acceptance of migration are fundamental factors for our development. They set an example of the human capacity to share without limitation and grow together seamlessly, living alongside one another in hexagonal houses. People are moving: the world is taking on a new form. Dellbrügge and de Moll are already there, waiting for the rest of us to catch up.