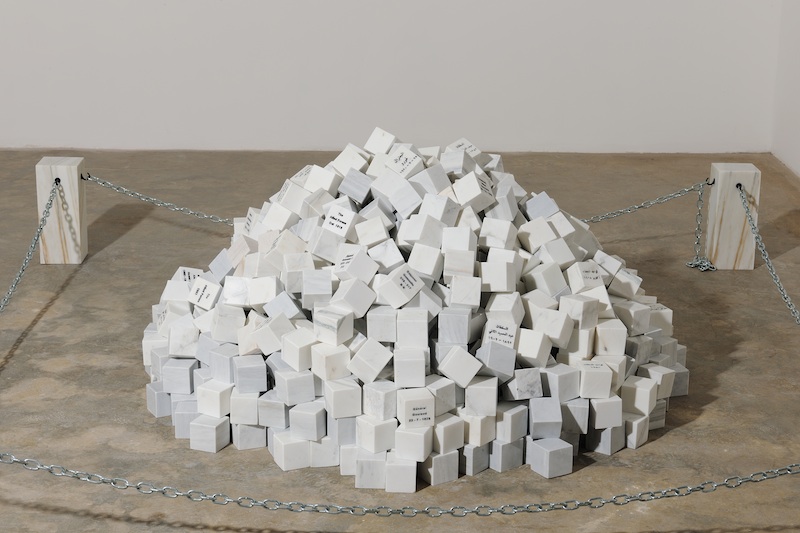

How can we capture and represent a changing world, caught in the moment of transition? In the work of Marwan Rechmaoui, a large floor-based black rubber map delineates the entire city of Beirut, sixty individual pieces marking roads and neighbourhoods. In others, flags hang overhead, emblazoned with the symbolic forms of buildings accompanied by bold Arabic writing; concrete and bent mental pillars appear as both crumbling, half-destroyed apartment buildings and minimalist sculptures; cubes of Carrera marble are piled high, engraved with the people’s lifespans.

Born in Beirut in 1964, Rechmaoui left at the age of nine, moving to Abu Dhabi and, eventually, to New York. Initially working as a painter, he was interested in exploring social realism and abstract expressionism. Today, the artist lives in Beirut again, having returned in 1993. His practice examines both urban development and social history. Architecture is referred to by the artist as an expression of urban life in Lebanon, a “way to talk about demography, migration, borders and behaviours”. He examines the physical and social formations that comprise Beirut, a city that remains conflicted, and which lies on the edge of a region’s continued instability.

Marwan Rechmaoui: ‘Beirut Caoutchouc’, 2004-2008, engraved rubber // Courtesy of Galerie Sfeir-Semler

Louisa Elderton: I’m interested to know what migration means to you, both historically in terms of your experience of growing up in Lebanon, and today in regards to the refugee crisis?

Marwan Rechmaoui: I would only comment here about the difference between immigrants and refugees; an expat is an explorer looking for a certain experience, while a refugee is obliged to experience a certain situation not necessarily looked for.

I did not grow up in Lebanon, rather in the Gulf, and later in the States: Beirut is my latest station. Station is a word, or a phase; in my conscious state I do not like to dwell much on earlier phases, but I am aware that this “migration” is what has shaped and is still shaping who I am today.

Paul Celan said: “No one bears witness for the witness”, how can I talk about the refugee crisis when I never experienced it.

LE: How did you experience Beirut changing as a city after the end of the Lebanese Civil War in 1990?

MR: Beirut after the Lebanese civil war; there was a hype around reconstruction, certainly there was this ascending process that everybody felt in the city, whether people were with or against the government’s plans to rebuild Beirut, everybody wanted to participate; critical thinking and debate about reconstruction and urban planning were on a rise, from journalists to artists, coffee shop talks, it was boiling and points of view were still being validated until all that came to an end with the assassination of the Prime Minister in 2005.

Marwan Rechmaoui: ‘Spectre’, 2006-2008, nonshrinking grout, aluminium, glass, fabric // Courtesy of Galerie Sfeir-Semler

LE: How has this shift informed your artistic practice (I’m thinking about works such as ‘Spectre’ and ‘Beirut Caoutchouc’)?

MR: It is not a coincidence that you chose two works revolving around a transitional period (one in 2004 and the other in 2006), separated by 2005 or the assassination of the Prime Minister, which shook Lebanon for a while. ‘Beirut Caoutchouc’ is a highly critical work that is concerned with issues about urban planning in terms of distribution, volume and accessibility, while ‘Spectre’ is more about the occupants of a building in Beirut, and their dynamics under such circumstances; that could tell about how the shift of power could dictate the focus.

LE: Why have you chosen to use your specific artistic materials—including cement, glass and rubber—to make your works? What is it about these materials that interests you?

MR: Whether it is made of one element or more, material is about quality and character. The qualities of each element are unique, and that is worth understanding. Usually ideas suggest the most suitable material to be used.

LE: Your work ‘Veni, Vidi, Vici’ is based on paintings by Cézanne of Mont Saint Victoire. What interested you about Cézanne’s approach to painting and would you cite any further historical artists as having influenced your approach to making your own art?

MR: Inspiration is usually the beginning of a creative process that ends up somewhere way beyond the initial idea. In the case of ‘Veni, Vidi, Vici’ it took an invitation to show in Aix en Provence to think of Cézanne’s painting of the mountain and his interest in form, which led eventually to Cubism. From there on, the work departed to a different realm.

Any artist can become an influence in a specific period, depending on the phase. For example, Rembrandt was not an artist that interested me when I was at university, but he became key for me in the last 10 years; I mean influences change a lot, according to different priorities.

Marwan Rechmaoui: ‘Veni, Vidi, Vici’, 2013, marble blocks, engraved // Courtesy of Galerie Sfeir-Semler

LE: What are your thoughts on the current state of global politics: Brexit and Trump’s election in particular? What is the perception of this in Beirut, among your own circles?

MR: In times of crisis like these today, when economy and identity feel threatened, people tend to worry more, and that can lead in many cases to conservatism and extremism. My friend Hussein, for instance, would talk about the Liberalism that dictates respecting the point of view of the other; he would funnily add that Trump has a point of view that we are trying to understand, we being the people who are receivers. This can be elaborated on further; he could even ask you about your point of view regarding the election of Aoun as President for the Lebanese Republic. I guess people among my circles are split between being amused by the Surrealist scene and/or shocked by where the world is heading.