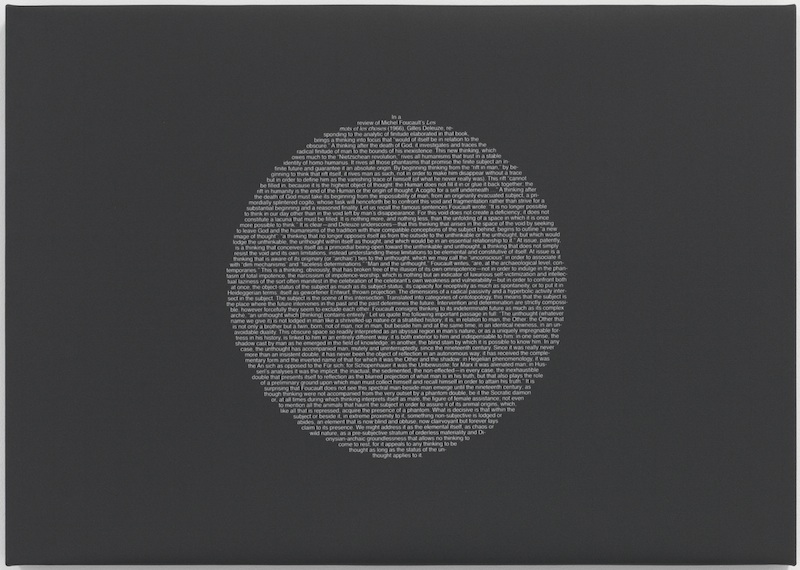

Printed in a closed circle, on one of the canvases in the foyer of Mitte’s BQ gallery: “But it is not something interior that makes an outward appearance nor something wholly other. It is something whose existence is at least precarious, for it exists only in the mode of not-being. ‘In each genuine artwork something appears that does not exist’. But it is not something interior…” Unlike the works of artists like Jenny Holzer or Steffan Brüggemann, Marcus Steinweg’s texts are not statements, but theses. Some come in the form of flowchart-style diagrams, others follow shaped lines or are bounded within circular paragraphs; regardless, reading theory in 12-point font under gallery fluorescence initially feels like an ascetic act: something only done, as the exhibition is titled, ‘For the Love of Philosophy’.

Marcus Steinweg: ‘For the Love of Philosophy 4’, 2017 // Courtesy BQ, Berlin, Photo by Roman März, Berlin

Steinweg doesn’t identify as an artist, but rather as a theorist who works in the field between philosophy and art, and many of his writings argue for their similarity in ethic and mission. In ‘Nine Theses on Art,’ published by Art and Research in 2009, Steinweg writes: “Art and philosophy have an inherent absolute resistance to doxa [— i.e., generally accepted knowledge]…because they compel the subject to decelerate, to brake itself, to renounce power.” Artworks, like philosophy texts, compel a reading—one that is slow, considered, and resulting from the reader’s rejection of power (to continue scrolling, to walk away from the canvas, to dictate what is normal in this world).

These pieces recognize their own fragility of meaning, as textual works in the image-based economy of the art world and 21st-century attention span, but also simply as texts and artworks. As a result, they can stage some fundamental questions on form: is it actually ascetic to read theory under gallery lights? How are artworks supposed to be read? And why must philosophic discourse exist only in a book or via a lecture? ‘For the Love of Philosophy’ could also be thought of as a multi-sensory, expanded form of the philosophy lecture (the exhibition program also includes two live lectures). Or the theoretical text enacted through a gallery exhibition. Or, because of its five guest artists, a compilation selected and edited by Steinweg. However, these analogies rely again on the division of art and philosophy, and the vessels or packages in which we expect them to be delivered.

Marcus Steinweg: ‘For the Love of Philosophy 10’, 2017 // Courtesy BQ, Berlin, Photo by Roman März, Berlin

Although all the guest artists’ pieces appear much more like artworks than Steinweg’s, or are read more in the manner we’re used to, they all call attention to precarity, voids above which our sense of truth dangles. ‘Freudian Slip’ and ‘Homesick’ are two black and white prints by Rosemarie Trockel, hung side by side. The former is a photo of two photos: one, the truncated shoulder and a few strands of hair; the other, a woman looking down, her face split by spotlight and heavy shadow into which her shoulder fades, the letters “PHILO” cut off in the lower right corner. Does Trockel suggest philosophy, or the 1st Century Jewish philosopher Philo of Alexandria, or the fashion designer Phoebe Philo, or all of the above?

Trockel’s ‘Homesick’ is seemingly more straightforward: what looks like a jewelry advertisement with a coy model looking into the camera, and a barcode, again in the corner. However, one has the sense that Trockel’s prints are highly referential: no one could figure out who the model in ‘Homesick’ was, but everyone thought she looked like someone; the barcode contains the ISBN to Hannah Arendt’s 1958 text ‘The Human Condition’, something I never would have identified had someone not pointed it out to me. To what they refer is open-ended, innumerable, indefinable: ‘In each genuine artwork something appears that does not exist.’

Rosemarie Trockel: ‘Homesick’, 2017 // Courtesy Sprüth Magers, Photo by Roman März, Berlin

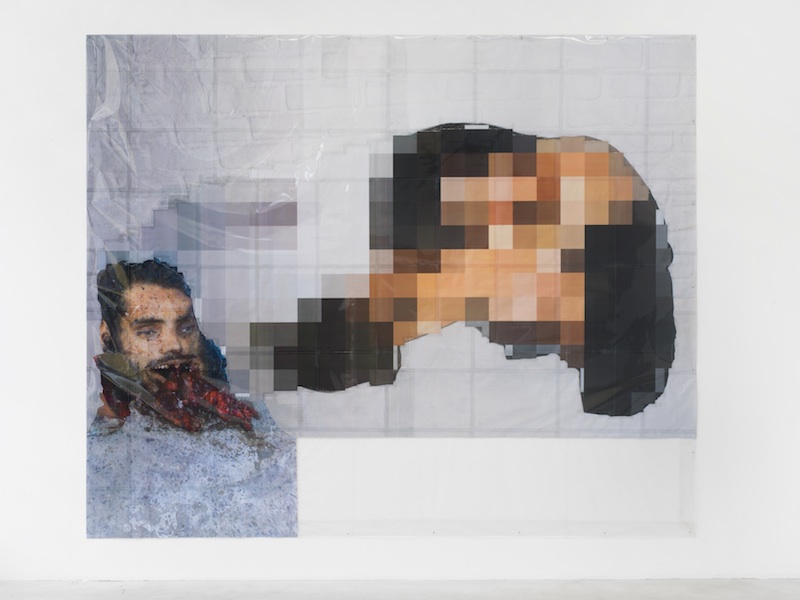

Among so much quiet intellectual play, walking into BQ’s back room to see half a decapitated head and the bloody pulp of a lower jaw is a shock. To the left of the head is a pool of black liquid, a pixellated beige form in its midst. And, if we’re allowed to see the gore, one must wonder what is hidden behind the pixels (which are actually analog: individually cut squares of paper). Thomas Hirschhorn started creating these “pixel-collages” after seeing more and more obscured photos coming back from post-9/11 Afghanistan, the results of American militarism blurred out in American news. Rather than hiding the violence, he used the pixels to cover up some other detail in these appropriated images, finding that it was not what was covered, but the pixels themselves that began to suggest authenticity and truth.

Surely, ‘Pixel-Collage No. 77’ provides a visceral and more acutely political counterpoint to the rest of the artworks here. But it could also reference Steinweg, writing in an Art and Research interview, “…I want to make Art in headlessness. ‘Headlessness’ stands for: doing my work in and with precipitation, restlessness, acceleration, generosity, expenditure…stupidity, self-transgression, blindness and excess.” Hirschhorn and Steinweg have collaborated throughout the years on “maps” that look much like the adolescent versions of the textual works at BQ, endearing and playful. They draw in the body when you read them (which, for the same reason, may be why I prefer the shaped texts over the diagrams in ‘For the Love of Philosophy’). For instance, the ‘Nietzsche Map’ from 2003: on a huge piece of paper, red and blue marker-drawn lines veer and swerve with the unsteadiness of a hand-drawn stroke; they connect photos (of Friedrich, of Foucault) and text printouts taped to the backing, or written on directly (“ETHICS”); they circle and perforate themselves, mark spots with Xs, are often illegible.

Thomas Hirschhorn: ‘Pixel-Collage No. 77’, 2016 // Courtesy BQ, Berlin and Thomas Hirschhorn, Photo by Roman März, Berlin

A massive flow-chart diagram of quotations and Steinweg’s commentaries is the closest analog here, and it’s dizzying, cold, a bit sublime. In one cell, he writes: “Love, in its opening towards difference, and philosophy, as the exaggeration of thought towards the unthinkable, are connected by a recklessness…” As these works don’t appear headless, perhaps Steinweg stages for us an intellectual recklessness: the appearance of an order that truly struggles against itself, as the texts all speak to a lack of stability (of meaning, of presence, of factual knowledge, of the subject itself). But love is much more effectively felt—sloppily, heedlessly—than graphed. Moreover, that head in the pixel collage once belonged to someone and was someone. An embodied philosophy could begin to give that person due tribute, whereas the digital prints suggest abstraction, authority, the standard fare of white men and white cubes. Truly, I believe in the radical potential Steinweg attributes to philosophy and art, but only when they stimulate praxis and enactment. As the artist himself writes, “The truth of love is experienced rather than known.”

Exhibition Info

BQ

Marcus Steinweg + Guests: ‘For the Love of Philosophy’

Exhibition: Jan. 17–Mar. 11, 2017

Lecture by Marcus Steinweg: Mar. 10, 2017; 8PM

Weydingerstraße 10, 10178 Berlin, click here for map