by Rebecca Partridge, studio photos by Berta De La Rosa // Mar. 28, 2017

There are few contemporary artists whose practices travel the same imaginative distance as Charles Avery‘s. Initially a ten-year project, now a lifetime endeavour, ‘The Islanders’ is an entirely visual and textual depiction, part-excavation, of an imaginary island and its people.

Exhibitions of Avery’s work allow us to enter the Islanders’ world through constellations of drawings, sculptural objects and texts: the narrative framework being crucial to the broader structures of the project. We are introduced to the Island by ‘the Hunter’ who arrives on its shores with a view to being its discoverer (which he soon finds is not the case). The Hunter is a protagonist from the ‘real world’, a narrator who simultaneously connects the imaginary world to the idea of an outside. There are other visitors, tourists who bring back objects that then appear as sculptural relics, physical objects which we encounter in the gallery. Views into the Island consist of drawings, sometimes of epic proportions, that describe scenes of daily life and its frenetic activities, bars, restaurants and municipal buildings rendered in great detail co-exist with vast swathes of formless wildernesses and geometric infinities.

Initially these glimpses have a fragmentary feel and exhibitions form no linear history, however the internal structures are coherent and potentially mappable to the investigative viewer. A centre point in an endless archipelago curving outwards in Fibonacci sequence, the Island is timeless—literally without time. Instead, there are non-sequential eras named after geometries: ‘the era of the hexagon’. It’s a realm of ideas, a subjective, open, expansive world in which to explore fundamental philosophical questions while also musing, not without humour, on art history and the art world within which the project is brought about. In 2013, the artist invited curator Tom Morton to curate an exhibition at ‘The Museum of Art Onomatopoeia’, named after the Island’s capital. The possibilities are endless.

On a quiet back street in Homerton, a long time down-at-heel area of London, behind an inconspicuous glass-frosted frontage, is Avery’s light-filled and airy studio. It is split level, with an office space above, a workshop and space for a variety of creative activities below. Avery enthusiastically shows me his heated drawing wall, an ingenious solution to the environmental problems of damp and cool, previously encountered when drawing. At the far end of the studio is a tree-like sculpture, built from cast bronze and fluorescent plastic. ‘Tree No. 5’ is an example of fauna to be found in the Island’s municipal garden, the Jadindagadendar, its synthetic construction based on mathematical principals: a product of the Islanders refutation of nature. There are other objects that have been ‘transported’ into the studio; a shelf lined with jars of Henderson Eggs (pickled in gin, a form of currency to which the Islanders are addicted), a strange looking animal on the table. There are several heads, cast from friends of the artist: vehicles for geometric hats at various stages of construction. The hats are clearly important, they could be read as schools of thought, ideas emanating from busts which here have the appearance of death masks. Avery describes this ‘petrification of things’: “when you take something away from the Island, being the subjective realm, and you bring it into the objective realm, it can only be a reflection of itself or fossil”.

The statis of the objects emphasises the vitality found in the drawings, which fill the studio. There is a real feeling of embodiment in mark-making, the activity of which can be traced in the visioning and re-visioning of characters and scenes. Avery embraces failure, making no effort to hide mistakes, though this translates more as an attitude than an actuality, as he is an astonishing draughtsman, a point made ever more impressive considering he draws almost entirely from imagination. He explains the intense and physical engagement the drawing demands: “You don’t have an object-paper-mind relationship, you just have a paper-mind relationship. You have to imagine every aspect of it because it is being built in your mind and therefore you find yourself really inhabiting the thing you are drawing”.

The drawing wall is magnetic and works in progress can therefore be moved around effortlessly. There are an array of inks and pencils, rulers and templates, the placement of which indicates a fluid working process. This flow continues in the subject matter. “There is always a sense of continuation with the drawings”, say Avery, “or that they continue beyond the picture plane, they are left a bit open ended. It’s not about the picture but that this is a picture of something else, something elsewhere. The objects serve the opposite, precisely to be objective. They contrast, their physicality and the way you engage with them is completely different”. He describes his relationship with the process of making the objects as a much healthier one: “the drawings, because of the way they come about, give me a whole bunch of pain. I think with the objects it’s a far more pleasant relationship because I go through several iterations and find the best possible solution and then it’s case solved. I don’t go away and love it one day and hate it the next day and agonise over it, it’s just done”.

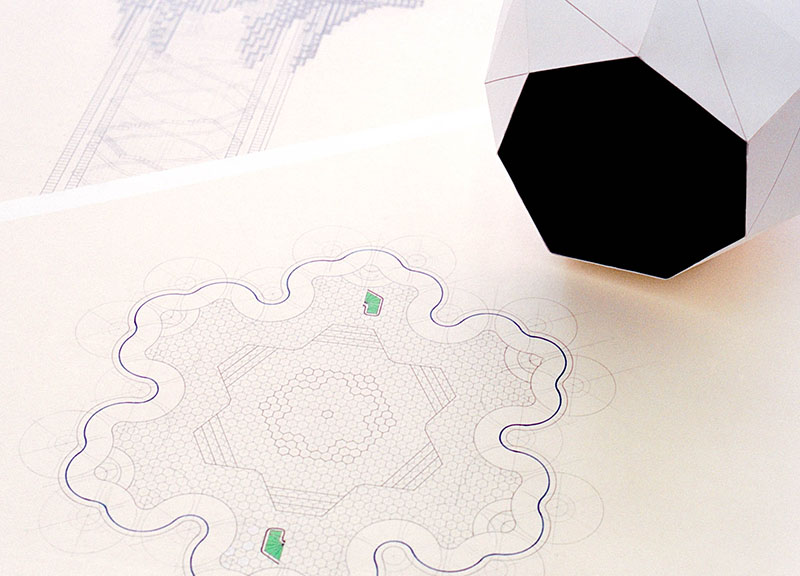

These differing relationships to making are clear when walking around the studio and it is apparent that constructing this possibility plays a role in Avery’s larger practice. In another area a large architectural drawing board supports a meticulous geometric drawing, part of a plan for the zoo. The precision and predictability of these complex geometries contrasts the fluidity and imaginative demands of the narrative works. A textual description of the visionary experience of Knot Faah, a prophet thought to have encountered the mythical Noumenon, invokes images of pre-Socratic geometries, a language married to mysticism. Knot Faah goes on to spend his life making ‘dotty paintings’, which may then physically appear as exhibited works. “It opens up another oeuvre for myself that I can do in the name of Knot Faah. When I am doing this very high concentration work sometimes I just want to go and paint blue dots for a while! I love the rest the geometric work gives me, the harmony and the mathematics is restful. It removes me from the structure, it’s a way out”.

This multivalent framework has broader implications. Here, fiction opens up a space where critique and possibility can co-exist and where the artist is not required to take any one position. Thinking about fiction as facilitating multiple modes of thinking brings us back to the idea of ‘fantasy’, a term that doesn’t sit well with Avery. “The term fantasy conjures quests and allegory which are very linear,” he tells me. “The Island is non linear. It’s not fantastical in any way, the gods are fantastical maybe but all gods are really, aren’t they? Really the Island is just another place…” The proposition here is that the real is not privileged over the unreal: “If I said to you I had a dream last night… there was a dog and it got on the table and was smoking a cigar, and then you said to me ‘but that’s not real’, you’re not saying I didn’t have the dream, you’re saying the facts of the dream do not cohere with the facts of reality, you are not disputing that the dream happened. Because the Islanders don’t entertain a mind-matter duality, everything is real, everything is part of a continuum of phenomena”.

For the reality of the Islanders to really come to life requires a leap of faith but, once taken, journeys into a realm of shared subjectivity and imagination await, where the viewer plays an active role in uniting the terms set out by the artist. Ultimately, it has its own life and momentum beyond Avery, who doesn’t see the work as ever being finished: “If you finish a work, you kill it. The Islanders will always be alive, even when I am not”.

Artist Info

grimmgallery.com

inglebygallery.com

pilarcorrias.com

Exhibition Info

DRAF

Charles Avery: ‘Study #15. Untitled (The Ninth Resort)’

Exhibition: Jan. 20–Apr. 8, 2017

Symes Mews, London NW1 7JE, click here for map

Writer Info

Rebecca Partridge is an artist and writer based in Berlin. rebeccapartridge.com