Deville Cohen’s video, sculpture and performance works visualize an attempt to understand one’s immediate reality through metaphorical environments that undulate between function and fantasy. They reveal the confusion and absurdity in systems of representation that define our daily activities. Strategically, he uses and subverts the emptiness of the black box—typically used in theater—as a backdrop to all of his works. He sees immense narrative potential in mundane objects and has the unique ability to transform them into magical characters. There is a capricious and irrational logic generated by Cohen’s work: performers struggle to participate in the impossible tasks assigned to them. Sets, characters, and props become entangled in psychic dramas saturated with humor, desire and anxiety.

Last year, I was lucky to see Cohen’s first staged production, ‘UNDERLINE’, which was commissioned for the Munich Biennial at the Deutsche Oper Berlin. In ‘UNDERLINE’, pink cotton candy blows up from its machine, becoming a whimsical extension of a dancer’s arm, and stacks of orange traffic cones shift to characters in a Sisyphean task. ‘UNDERLINE’ sends the viewer on a surreal journey to the boundaries of imagination, while reflecting on human limitations.

Deville Cohen: ‘UNDERLINE’ at Deutsche Oper Berlin // Courtesy of the artist

Stephanie von Behr: How does the role of fantasy play out in your art practice?

Deville Cohen: I often cull from science fiction or fantasy source materials. The storyboard and structure of ‘UNDERLINE’ is based on my interpretation of several key notions from the book ‘Flatland’ (1883) by E.A. Abbott. I am interested in the novel’s concepts, such as mysterious appearances, physical violence, perception management, body images, and limitations, rather than its storytelling elements. The characteristics of cotton candy, as a sculptural material, represent for me the mysterious appearance of the three dimensional sphere into the two dimensional flatland; the body being waxed is related to instances of physical violence that appear in the book; the pile of traffic cones and yoga balls is my version of geometric progression; and the architecture of the Amusement Park’s stylized ride represents an artificial and controlled environment. Once I abstract and translate notions into my system, I structure them into a new formation of inner relationships with their own logic. At this point, I can leave the source material behind since it is inherently contained in the vocabulary of the piece. I am more invested in my application of the translated notions to the fantasy I am creating.

Deville Cohen: ‘UNDERLINE’ at Deutsche Oper Berlin // Courtesy of the artist

SvB: Abstraction plays a big role in your work but you manage to distill concepts without losing substance. How do you direct your dancers and musicians to embody abstraction?

DC: For ‘UNDERLINE’ I created a name for my staging and direction method: “Music Theater as Kinetic Sculpture”. The stage became an extension of my studio and everything turned into a material to sculpt with. This approach was not only applied to the sculptural sets and props, but also to the way I was working with the performers, the musical instruments, and the music itself. The function of the performer’s strict actions were to serve as human operators of a kinetic sculpture. They transformed the physical elements on stage in order to visually depict the scenes. Four dancers and four musicians were constantly busy with visual and sonic actions to the music and instrument design of the composer Hugo Morales. Their entire energy was invested in creating representations that were exterior to their bodies. This lack of hierarchy between image, sound, body or object concentrated the piece into a hermetic system, from which I could then manipulate it from the outside as one object: a kinetic sculpture composed of layered materials and elements. The performers were often frustrated and exhausted when they could not find themselves, as performers or individuals, within this insurmountable structure. As we progressed in the process, they managed to master and control the elements in the constructed environment and suddenly could create temporary islands of “liberation”. As liberated individuals, within those few seconds throughout the piece, they could apply and exhibit their own form of subjectivity through personal techniques and aesthetics.

The cotton candy is a good example because cotton candy as a sculptural material is actually impossible. It is delicate, unreliable, extremely sticky to touch, and very difficult to maintain as a constant string. The cotton candy machine is also very moody, depending on its temperature and the amount of sugar applied to it. Asking the dancers to maintain a constant string structure and move it on stage from point A to B was challenging. The machine and the candy were in control, and the dancers needed to adjust and apply their actions according to it.

Deville Cohen: ‘UNDERLINE’ at Deutsche Oper Berlin // Courtesy of the artist

SvB: How do you come up with these magical moments in your work?

DC: I often start with a problem.

Or with something personal.

Or with a personal problem.

I spend a lot time with each object and element and I get to know them very well. The next step is to get totally lost in them. So the “magical moments” might come as a result of getting lost in a system that is somewhat random, but I am totally committed to the struggle of making sense of it. There is a large amount of preparation, research, and conception that I need to do before I can actually let go and be intuitive. It’s a highly informed intuition. But, when things fall into place, they make total sense to me and I am going with them, no matter how impossible, absurd or abstract they are.

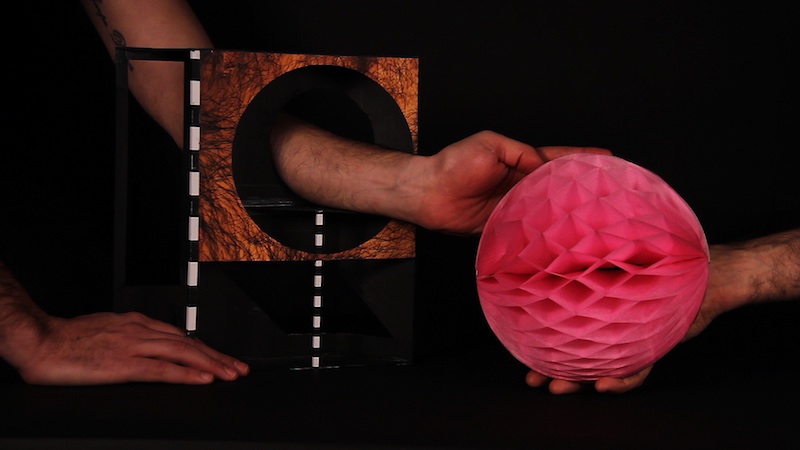

The magic, then, is not an outcome of a “suspension of disbelief” but an acceptance and exploration of whatever that solution is. I believe in the power of an image, the reality of representation, and in formality as a container for meaning and purpose. The “pure” idea of a pink circle, for example, is not contained or limited to each of its manifestations on stage in the variety of materials and dimensions it takes on, as a yoga ball, a piece of wax applied to a hairy body part, a paper ornament, or a nipple. The shape itself is fluid and travels in between those representations.

SvB: What are you up to next?

DC: Working on ‘UNDERLINE’ for more than two years made me realize that the process of creating a theater-based live performance and its outcome resonate deeply with my interests as an artist. Collaborating with dancers was an incredible experience. I learned so much from them about process: how to bring presences and expression into representation. I am working on another “sculptural dance theater” piece as an interpretation of the cinematographic chase scene.

Metaphysically, the anxiety of the chase scene is also inspiring me to escape, to be liberated, to find safety even in the most dangerous, impossible and dire situations. The cinematic chase relies heavily on high production cinematography, rapid editing, and fantasy. I am interested in how these dynamics of thrill and danger can be translated to the sculptural reality of the theatrical stage.

Deville Cohen: ‘UNDERLINE’ at Deutsche Oper Berlin // Courtesy of the artist