In an exhibition of new works, Greek artist Jannis Varelas presses the pause button to focus on intimate, in-between moments of daily life. Alongside three paintings, the four videos in the exhibition—entitled ‘MONSTER’ and on view at the Onassis Cultural Center in Athens—repeatedly play on loops, never offering a complete narrative or resolution. Each subject—be it a robber preparing for a robbery or a ballet dancer unable to separate his hands before a performance—is entrapped in a moment of uncertainty or, according to Varelas, a moment of dystopia.

“In-between moments don’t exist in reality,” Varelas says when we meet at the exhibition. “The loops give substantial time to these awkward, in-between moments, which are more interesting—formally, sculpturally and existentially.”

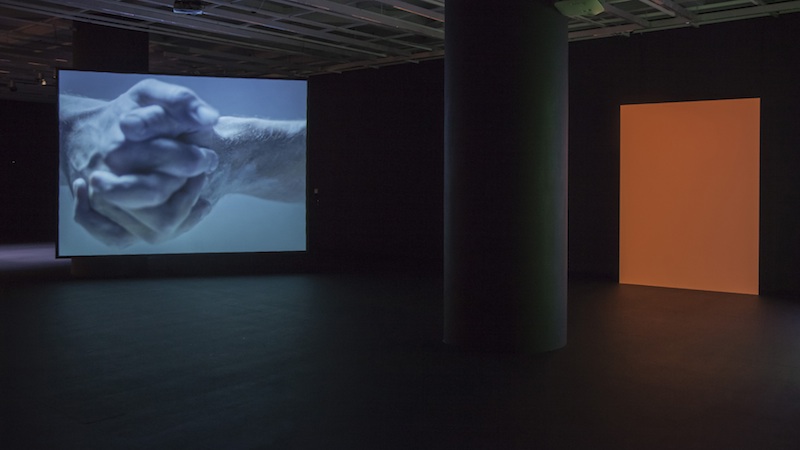

Jannis Varelas: ‘White Swan’, 2017, video 7 // Copyright Andreas Simopoulos, courtesy of the artist

In his video ‘The White Swan’, for example, viewers watch as a dancer’s hands twist and turn, struggling to become free of each other. In the background, sounds of the dancer performing the ballet can be heard. Viewers know what the ending should be (his hands separating, allowing his body to dance), but it is never reached. Instead, the dancer is perpetually caught in the moment of preparation.

Varelas’s paintings, though static, also invite the consideration of in-between moments. The painting ‘A Couple of Notes on Hannah’s Dream’ is composed of 10 individual canvases, each of which presents the same dream in a different iteration. A dream, quite literally, results from an in-between state of mind, neither conscious nor unconscious, neither awake nor asleep and, in the 10 canvases, symbols like mushrooms and a specific cartoonish face reappear. The face itself, according to Varelas, is a moment “between lust and devastation. It could be something that is very joyful but also very desperate.”

Just before the opening of the exhibition, which is on view until July 16th, we spoke with the artist about specific works and his interest in the in-between.

Jannis Varelas, installation view ‘MONSTER” at Onassis Cultural Centre // Photo by Andreas Simopoulos, courtesy of the artist

Emily McDermott: Can you tell me about the video ‘The White Swan’?

Jannis Varelas: It’s a reference to ‘Swan Lake’, because I think swans are very difficult animals. There’s always a very strict conflict between the white swan and the black swan, which creates a very classic reference for what I wanted to show. What you hear [in this piece] is the reversal of the dancer, who plays the White Swan, dancing the piece. What you see is his hands trying to separate in order to dance, but it never happens. The hands cannot be separated. He has the steps in his mind, but he’s unable to do anything. It’s a piece about a dystopian moment, a moment in which he cannot do anything, and he is obliged to fight for something that is really important to him.

We asked him to do a choreography of himself not being able to perform; we didn’t tell him to use his hands. We said, “What do you do usually before you start?” And he was standing with his hands together and said, “I don’t know.” I said, “Wait a minute, what about that? What about a choreography as if your hands couldn’t get away?” To dance, you need everything. So, what you see is the exact opposite of what you hear: you hear him dancing, the steps and the rhythm in reverse.

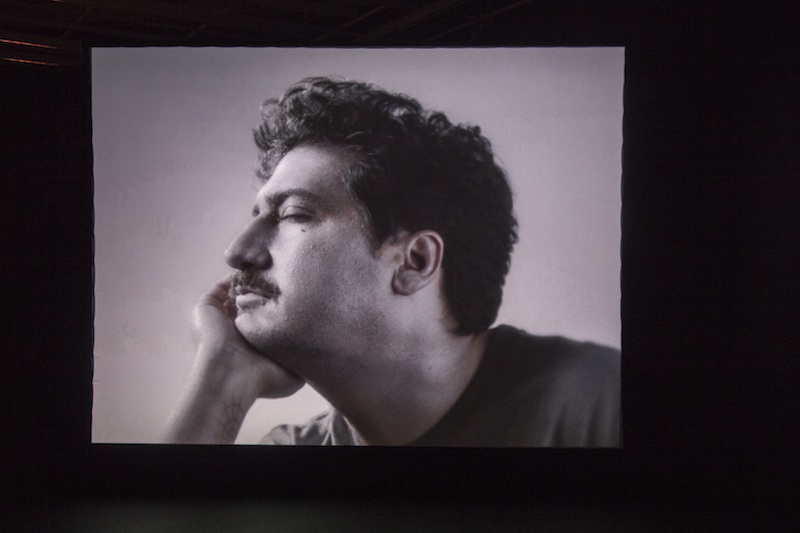

EM: I also want to talk about ‘Bank Robber – Don’t Forget Your Kata’, in which the robbers wear masks of your face.

JV: The piece has to do with the situation in which someone is preparing for something. Here, a bank robber is doing karate before the robbery. At the end of the day, he’s entrapped in that; we never see the robbery, we never see the action of who he is and who he wanted to be. You only see the trap of the loop: the preparation for something that is very important becomes the actual reality, the cage.

The masks are based on what you have seen in movies, like bank robbers wearing masks of presidents, but we produced two masks of myself. Bank robbers wore masks of the president’s face because they wanted to symbolically incriminate the president for stealing the money of the people. In a twisted variation, this is the incrimination of the artist’s self-promotion.

Jannis Varelas: ‘Bank Robber – Don’t Forget Your Kata’, 2017, installation performance // Photo by Andreas Simopoulos, courtesy of the artist

EM: You have an ongoing interest in childhood trauma. Two works, collectively titled ‘Two Paintings’, in this show are based upon children’s drawings. Can you tell me about these pieces and this specific interest?

JV: The two paintings are based on two kids’ drawings with traumatic experiences. One drawing was a little girl dressed as a witch trying to meet a butterfly, who then put all of this weird red paint [on the surface], creating a very pensive situation. In the other, the kid was drawing cities and then destroying it with his crayons, making it a crazy abstract surface. I enlarged both of them and inserted elements that also have to do with adult vulgarity. It’s a combination of the two worlds: trauma as a kid, then as an adult, pornography and advertisement.

I have a big archive of drawings from teenagers that have dyslexia or ADD, because my mom used to work a lot with that when she was younger. I helped her do classifications. Absentmindedness was always in my interests as an artist, so I had all of this research. I even have drawings that people made while they were on the phone because that was research: people wanted to find a pattern about this absentmindedness status to see if they could find a synchronicity between the hand and brain waves. They didn’t find shit but they’re still searching.

EM: Were you absentminded as a child?

JV: As a child, not at all. Nowadays, it’s complicated. [laughs] I always found it very interesting how things are developed through the impossibility of being young and how the learning process starts when you’re born and it never ends. But somehow, socially, we stop the learning process at the age of 30 and we’re considered adults. It’s very interesting to try to understand the social structures and the state of a human being learning in society. I was thinking about that and cognitive structures in the social cycle.

Jannis Varelas: ‘Two Paintings’, 2017, mixed media on canvas // Photo by Andreas Simopoulos, courtesy of the artist

EM: Even if the subject matter is critical, your works always seem very hopeful.

JV: I think about dystopia as a real fact and what I want to project is that in any dystopia there is hope, there is a way out. The recognition of a dystopic situation is what will help you get out. If you don’t recognize it, if you don’t have it as a cognitive status in your mind, then you aren’t going to get out. If you embrace the dystopic situation, then you can get out with a smile.

EM: I’m also curious about the tension between high and low in your work. You use things like classical references to art history, as well as pornography.

JV: In each piece, you have two edges coming together. To be honest, I wouldn’t say that I’m specifically interested in this tension, but I recognize it in the structure we live in and I’m pointing it out. It’s an understanding that it’s in our everyday life. I don’t see it as a personal statement; I see it as a point of view toward things. It’s not “this is what I think.” It’s more like, “This is what I saw.”

Jannis Varelas, installation view ‘MONSTER”, ‘Untitled’, 2017, video // Photo by Andreas Simopoulos, courtesy of the artist

Exhibition Info

ONASSIS CULTURAL CENTER

Jannis Varelas: ‘MONSTER’

Exhibition: Jun. 07 – Jul. 16, 2017

107 Syngrou Avenue, 11745 Athens, Greece, click here for map