Building a ‘Nationaltheater Reinickendorf’ from scratch in a former north Berlin ammunitions factory, German set designer Ida Müller and Norwegian director Vegard Vinge invited Berliners to test their limits in a 12-hour durational performance with no press texts, no interviews, and no straightforward explanation. As part of the Berliner Festspiele‘s ‘Immersion’ program, the performance ran 10 times over the month of July. It is not the first time Vinge and Müller have collaborated: in 2012 at the Volksbühne Berlin, they performed an unconventional adaptation of Ibsen’s ‘John Gabriel Borkmann’, and secured a reputation of creating absolutely wild, wonderfully vulgar theatre. ‘Nationaltheater Reinickendorf’—where human faeces, anal sex, and dildos are par for the course—is no different.

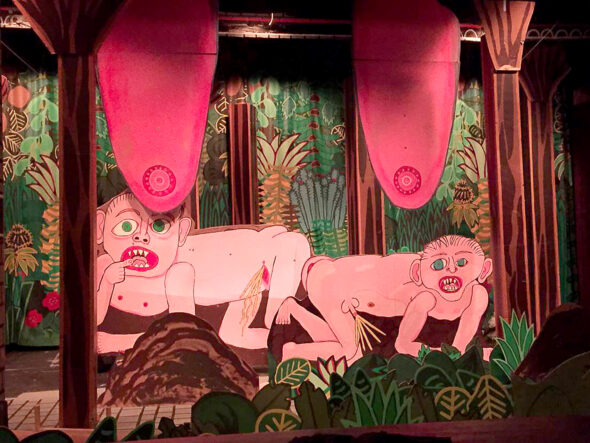

Vegard Vinge, Ida Müller: Nationaltheater Reinickendorf, 2017 // Courtesy of Nationaltheater Reinickendorf

The piece is not only a performance, but can be understood as a Gesamtkunstwerk. Müller’s spectacular set design includes of a hall of fame, a panini church, and a theatre announcing “Welcome to the Pleasuredome”, as well as other assorted contraptions. Hidden steps criss-cross into different compartments, and various, pre-filmed performances of the actors are screened onto multiple surfaces, as they sometimes reside motionless in glass cubicles while the films play. The complex, multifarious set is painted on, decorated, and treated like a canvas, on top of which several more paintings mimicking famous and beloved movie posters are propped. Critiquing the cult status given to commercial movies, these posters are extremely amateurish takes on Hollywood’s most famous movie posters and adored faces, with mismatched, block letters spelling out the titles—a far cry from the customary top-dollar, flawless graphics. A few penises are thrown on here and there as well, and Vinge auctioned off a handful of them for the price of €1 to audience members. The set is also adorned with a fountain-like sculpture of Vinge pissing into his own mouth.

Vegard Vinge, Ida Müller: Nationaltheater Reinickendorf, 2017 // Courtesy of Roman Hagenbrock

But aside from its provocative nature, ‘Nationaltheater Reinickendorf’ is also intellectually-informed. It incorporates adaptations of the classics—including Hamlet, Othello, and Ibsen’s ‘Baumeister Solness’—preserving their intense emotion in a contemporary context. Vinge and Müller also reintroduce old techniques of masked theatre, where actors are in distorted silicone, white-painted masks and wigs, speak in absurd, enhanced voices, and use contacts for the effect of drooping, disfigured eyes. At some point, they start to loose semblance to costume, and all traces of the individual and the human become hidden. In many scenes, phrases are often repeated for a painfully long time in crescendo, reminiscent of trauma and Freud’s repetition compulsion. Yet despite the actors’ freakish appearance, they manage to invoke some sort of sympathetic response. By doing so, Müller and Vinge challenge troubling trends of indifference to the Other, and restore a much-needed tension to the act of theater-making.