Turkish art critic, writer, and curator Beral Madra presented a recent lecture at nGbK as a part of the gallery’s regular dissertation program, furthering their statement of solidarity with Turkish artists after the exhibition, ’77/13 – Political Art and Resistance in Turkey’ and the event ‘After the Coup’ last year. The talk, titled ‘Art Making and Curating through the Passage of Post-truth’, examined Turkey’s political climate and the slow deterioration of freedom in Istanbul’s contemporary art scene. Madra speaks with grave concern for the future of art making and exhibition in Istanbul, due to the alarming increase in the privatization of galleries, the constant closure and lack of funding for artist-run initiatives and the rampant censorship of exhibition content.

This continuing assault on creative space and freedom of speech within art practice is due to Turkey’s slow dissolution of Democratic practices under Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, whose vision since his accession to power has been to move further away from secularism, abandon parliamentary democracy and adopt a one-man rule. The resistance to this increasingly autocratic rule by the people of Turkey resulted in the Gezi Park revolt of 2013 and the attempted Coup in July last year.

Amidst the censorship, the privatization, and the crumbling of artist-run initiatives in Istanbul’s art scene, Beral Madra assured her audience at nGbK that there are certain institutions and individual initiatives still determined to fulfil the aims and intentions of “unbiased democratic transformation, freedom of expression and communication, respect to pluralism, human and gender rights, responsibility on ecological problems and development of public awareness.” The post-truth era is a term now used to describe the cultural and political climate of our times, wherein objective facts have become less important than emotional persuasion in shaping public opinion. Frequently cited as clear indicators that we have transitioned into a post-truth climate are the cases of Brexit and the 2016 US Presidential Elections.

Beral Madra curated the first two Istanbul Biennales in 1987 and 1989, as well as the Turkish Pavilion at the Venice Biennale several times, was a part of the new art movement in Istanbul during the 1990s, has published a number of books on contemporary art, and regularly contributes to periodicals and magazines as an art critic. She was also one of the co-founders of the Kuad Gallery in Istanbul. I spoke with Madra after hearing her lecture at nGbK, to discuss some issues raised in her talk.

Ekin Onat, Objections, The Pavilion of Humanity, 57th Venice Biennale // Courtesy of the Artist

Kimberly Budd: You made a closing statement to your talk, “the whole world is looking to Berlin, Istanbul is looking to Berlin” and then went on to say that you hope for a counter-revolution, as “revolution is the best path for resistance and change”. Can you elaborate on this? Why is the whole world looking to Berlin?

Beral Madra: Looking from this side of the world, where the leading global powers are settling their accounts by provoking local enmities and racial or religious antagonisms to bloody wars, EU countries are like paradise. Despite the Schengen difficulties, creative people from Turkey and neighboring war zones try to arrive in Berlin and other centers to start a new life.

From the point of view of contemporary art—visual art, music, cinema, etc.— Berlin is the most democratic, most open to multiculturalism, most active and culturally organized city in the EU. For artists, academics, journalists and art experts who have lost their jobs or feel somehow threatened, Germany is now a safe haven. Paradoxically, this enigma is due to the political conflict between Turkey and Germany; conflict has created German support for Turkey’s intellectuals.

Evidently, I did not mean “revolution” in the Modernist sense! What I mean for these creative migrants from Turkey is to use this opportunity of living in a well-organized contemporary art infrastructure to work cooperatively and collectively, find new strategies of implementing contemporary art concepts and practices that can be exported to Turkey for a restoration of democracy. This sounds idealistic, but considering the population of Pro-AKP Turks in Germany, the voice and visibility of these creative people might be effective in explaining the truth to them; as they are spellbound with post-truth.

KB: What about Gezi Park? What did/does that mean for contemporary art now? I read that the majority of Turkish artists feel that the demonstrations were a radicalizing moment for society, that political art flourished and continues to, but then I also read a contradictory article on the subject, expressing the lack of contemporary work that is speaking out, that there is increased caution towards producing political art works. How intense is the individual censorship in the scene?

BM: The meaning and content of the Gezi Action was partly based on the rich memory of the artworks produced by artists for many years and on the texts introducing these works. We have seen how visual/textual/audio-visual material exhibited in the Gezi Action is influenced by post-modernism and relational aesthetics, which has been produced continuously since the 1980s.

Despite this fact, during the Gezi Action the press and the media always portrayed the art of consumption and entertainment as ‘art’. Fortunately, though, Erdem Gürbüz—the performance artist who acted with the spirit of the time—brought contemporary art to the agenda of politics and society through his performance during Gezi.

We hoped that this acceleration could become a milestone for the press and the media, which irresponsibly blended politicians’ understanding of contemporary art and the art of consumption/entertainment culture. Our hopes, however, were not fulfilled. Even if it was obvious that the only force that can still counteract negative structures on the horizon is contemporary art production, content, and aesthetics, the art scene has not organized itself accordingly.

The Gezi Action advocated vital issues on the axis of society and the city, as well as social and individual rights over the public sphere. This event shook up power and found global repercussions. While Turkey’s democracy passes through the vital exam, it can not be abandoned from activities that convey massive artistic thoughts and expressions from the main veins of democracy; but it is also inevitable to redefine and organize contemporary art concepts and activities according to the needs of this process. At this point in time, “art activities” can have an important role in the fight for individual freedoms, freedom of expression and other fundamental democratic rights. Some artists are producing very effective works and curators are realizing target exhibitions and attempting to find ways to bypass censorship and to avoid self-censorship.

Murat Göks: Border, In Search of Istanbul Today, 2010 // Courtesy of the Artist

KB: Could you give an example of ways an individual can use post-factual philosophy in their art practice, writing or curating, today?

BM: I think the coming 15th İstanbul Biennale and the exhibitions around the Biennale will show how the art scene will handle this complexity.

KB: How do you understand the idea of post-truth and its relationship to democracy?

BM: Post-truth, which roughly means manufactured through media-edited facts by political powers or neo-capitalist interest groups, is, in fact, the new name of old, polluted ideologies. On the other hand, to give a new name to old vices is to revive societal awareness, to shake off the dust of optimistic approaches and dreams. It is not easy to reduce democratic society–even if it is not perfect—to new forms of slavery. History will favour democracy on the battleground of totalitarian movements against democratic forces, that are thankfully still existing.

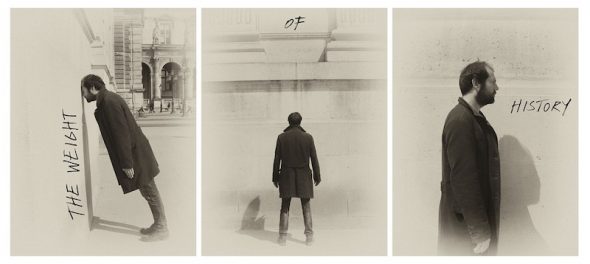

Çağrı Saray: The Weight of History, 2013 // Courtesy of The Artist

KB: How realistic is the occurrence of another counter-revolution in Turkey? Can you see another attempt happening in the near future?

BM: I cannot predict a counter-revolution, but the statistics show that at least 60% of Turkey’s population is looking forward rather than backward. The change towards democracy will mainly depend on the severe outcome of the now depressed economy, on the direction of the war in the region and the potential resistance of opposition parties. Not to mention the decisions of the global ruling powers on the destiny of the region.