Tomasz Kobialka’s new video ‘Pearl Diving for Wyrms’ explores intervention inside a contemporary gaming psychosis, but from the point of view of the gaming company rather than the player. A majestic dragon, soft-spoken and ripped from a previous game, informs the viewer of the business logic used by companies to monetise Free2Play games. The dragon acts as a sort of whistleblower; the dragon speaks of how the goal of Free2Play is to entice players to become socially and emotionally invested in their games, so they can exploit the users. Kobialka has entwined this watchdog narrative within ‘Openworm’, an open source reality in which the goal is to create the first digital-biological organism. So far, Openworm has successfully mapped a functioning brain worm inside a simulated computational environment. In a way, Openworm has developed the first form of computational consciousness. Berlin Art Link caught up with Kobialka before his new show opened at the National Gallery in Prague to discuss gaming as intervention and the art world as gaming.

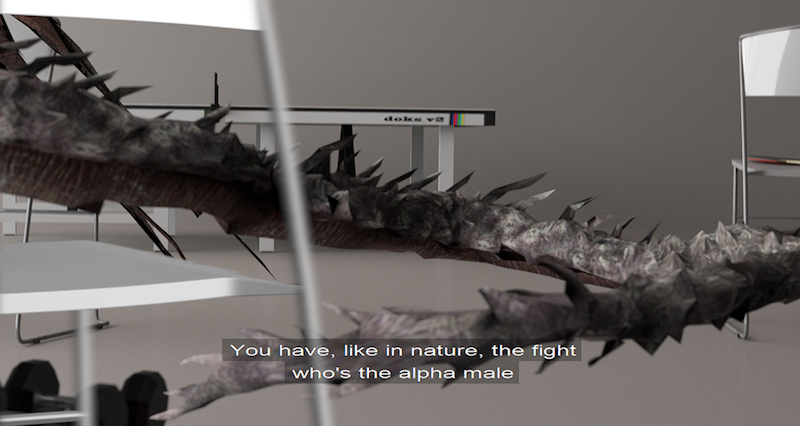

Tomasz Kobialka: ‘Pearl Diving for Wyrms’, Video still, 2017 // Copyright Tomasz Kobialka

Penny Rafferty: Your work often speaks about social and emotional investment. What exactly is that in the gaming field today?

Tomasz Kobialka: Well, the longer the player spends playing a game the more they become invested in the game and the more likely they are to start spending money. Time plays a role here, as does the feeling of accomplishment: these games will often have simple goals that frequently reward players, mixed with some sort of ranking system to promote competition amongst the group. Features like in-game chat or forums build social bonds and contribute to a sense of community. It’s a carefully refined system built around continually satisfying key emotional and social needs.

PR: The idea of monetary gain and social belonging, via video games, is not something a non-player would necessarily think of as crucial. Has this always been the case in gaming design or has it become bigger in the smartphone age?

TK: Generally, the majority of players won’t spend much, if anything, on a game: they form the audience. The top players are the ones that generate the most income. A player might begin to spend thousands of Euros a month (on a free game!) just to remain at the top of the leaderboard. It becomes a source of pride, it gives people meaning. The reasons why players spend so much money are varied and personal. These games didn’t exist 10 years ago, the technology and knowledge just wasn’t there, but the model has been so profitable that it is now an industry trend.

PR: Many people have suggested this is escapism, in the sense that the avatar becomes a hidden body, or potential body to the player. I assume this is where the intimacy can be exploited?

TK: In my work, the avatar appears as a dragon that is set as the central narrator and uncovers the logic of the games industry. The dragon was ripped (illegally copied) from a popular PC game, and its textures and polygons have been animated using 3D software. There’s a component of intervention in the dragon: I see it as a liberated software artifact (something very real), which reveals the modes of its own production. Intimacy is one of the affects that game companies profit off of, amongst others. A player’s satisfaction from leveling up, completing a goal, socialising, these are real emotional experiences. But the environment under which they are elicited is a synthetic one, constantly monitored and refined.

PR: The dragon is a very macho figure in a traditional sense, but you have turned him into a sort of whistleblower. The alpha male topic is constantly up for discussion as a toxic platform in gaming, but this desire to be the alpha is, in fact, also the reason why they can be milked for money and exploited.

TK: The logic of the alpha male identity construct is one rooted in competition. Not only does an alpha male need to make it to the top of the pecking order, but they need to maintain their position. An alpha is constantly in the shadow of competitors eager to prove themselves. This is similar to the logic that Free2Play games are very good at monetising. Games create conditions for social ranking and hierarchy and companies push game content to increase competition and maximise in-game spending. It’s a sort of sweet irony, the competitiveness of the alpha mentality is being used to generate income.

Tomasz Kobialka: ‘Pearl Diving for Wyrms’, Video still, 2017 // Copyright Tomasz Kobialka

PR: Can art function this way?

TK: I feel the art world may function in this way: competition as a framework for social organisation. In my own experience, competition has been used to determine who receives exhibitions, residencies and funding. A question I’ve been asking myself recently is whether the function of critique (uncovering modes of living and working) is useful as a technique for bringing about change or if the critique is just another form of social reproduction that re-articulates (and strengthens) existing power relations?

PR: This is interesting because you have just graduated and received quite a lot of awards from your MFA show, so in a sense, your “art game” becomes a real space of emotional investment in real time with real consequences? How does this affect your play?

TK: Straight to the bone. I’m totally implicated in the reproduction of competition. These are codes and practices I’ve adopted and have been reproducing over my life. The feeling of “winning”—achieving a goal, meeting expectations and receiving social recognition—is a by-product of this competitive mentality. I’m a workaholic, it gives me meaning and satisfaction. I guess I’m also searching, like everyone else, trying to satisfy emotional desires externally that might be better dealt with internally. Maybe I feel other aspects of my life have not been so great, so I’ve put all my energy into my practice. Recently, I’ve been trying to be more conscious of my actions and how they affect the people around me. Withdrawal from the “real world” seems inadequate, but so does blind reproduction – perhaps a middle ground can be achieved? Becoming conscious feels like a start.

Tomasz Kobialka: ‘Pearl Diving for Wyrms’, Video still, 2017 // Copyright Tomasz Kobialka

PR: The dragon speaks of competition, vanity and status in the game. Is this not the reality of any closed network, and can you see another possibility for the “human self”?

TK: I don’t think these are necessary universals or “essences” and I don’t buy the historical determinist argument that just because these things have existed in the past (“always existed”) that they should continue to be useful. The behavior of a network is emergent from the logic and material conditions replicated within the context of the network itself. With rapidly changing social conditions I think it’s useful (and a good opportunity) to rethink some ideas that humans have always thought were essential.

PR: One speaker in the video recalls the words “we are not two, we are one”. I assume he is talking about AI/machine and human – which is interesting when thinking of the idea of the intervention of the machine.

TK: This idea comes from a shift in speculative modes of philosophical thinking that focus on unsettling the human as the central agent of change in the world, which is an incredibly terrifying, exhilarating and humbling one.

Tomasz Kobialka: ‘Pearl Diving for Wyrms’, Installation view, 2017 // Copyright Tomasz Kobialka

PR: The art world moves very fast, in term of technology. We already see more VR-based works. Ed Atkins—who is arguably one of the first artists to use digital mechanics in his work—has a recent show at Martin-Gropius-Bau that seems to deliver the message that the potential of CGI is already dead, from cultural exploitation in the arts. Is this another fad or do you see the potential for an alternative art discourse?

TK: I think technology has a fad component to it that I’m really interested in. This feeling of hype is perhaps a byproduct of the idealism and potential that goes into technological development. VR offers a futurity, of sorts, away from the present. I guess what’s more interesting to me is pinning down effects of this hype on present reality. I feel that we are swimming in a multiple of realities all the time: the reality of my emotions, my (potential) growing cancer, the political context in which I am situated, the reality of climate change. As artists, how we imagine and narrativize the future filters down into the construction of reality. We have the potential to consciously shape cultural discourse rather than blindly reproducing it. I think the challenge lies in how to reproduce culture in such a way that brings about positive change and, for me, that lies in the attitudes that one takes to cultural production. As in my own practice, these inevitably become articulated in the work itself.

Artist Info

Exhibition Info

NATIONAL GALLERY PRAGUE

Group Show: ‘Startpoint 2017’

Exhibition: Oct. 19 – Dec. 12, 2017

Trade Fair Palace, Dukelských hrdinů 47, Prague 7, click here for map