Article by Ilyn Wong // June 20, 2018

The title of the two-person exhibition at Galerie im Turm, ‘Mighty Good Men,’ brings to mind the 1994 Salt-N-Pepa song ‘Whatta Man,’ the gist of which is that a good man, more specifically a “mighty good man,” is a rarity. In the age of #MeToo, this sentiment is all too appropriate. With a palpable sense of urgency, women globally have banded together in solidarity and protest against systems, cultures, legislations and regimes that have allowed the abuse of power to go unchallenged—power that has, for the most part, resided in the hands of men. In a way, femininity has gained heretofore unheard of power, while “masculinity” has almost become a dirty word, and often at one fell swoop, described as “toxic” or “fragile.” So today, with the understanding that gendered formations of identity are but cultural and historical mechanisms of control, should we also not find suspect the arch-figure of a “good man,” one who might even been esteemed as “mighty good”?

Installation view of ‘Mighty Good Men’ at Galerie im Turm, 2018 // Photo by Eric Tschernow

Curator Sylvia Sadzinski asks in the text that accompanies the exhibition, “What form and function do concepts of masculinity have in a predominantly heteronormative culture?” Beyond form and function, I would ask, is how do expectations of masculine display reflect and engender its own production? In a way, the very notion of masculinity—hetero or otherwise—is itself normative. In ‘Mighty Good Men,’ the artists Andrew J Burford and Constantin Hartenstein critique masculinity as fractured and troublesome, yet always inescapably hegemonic.

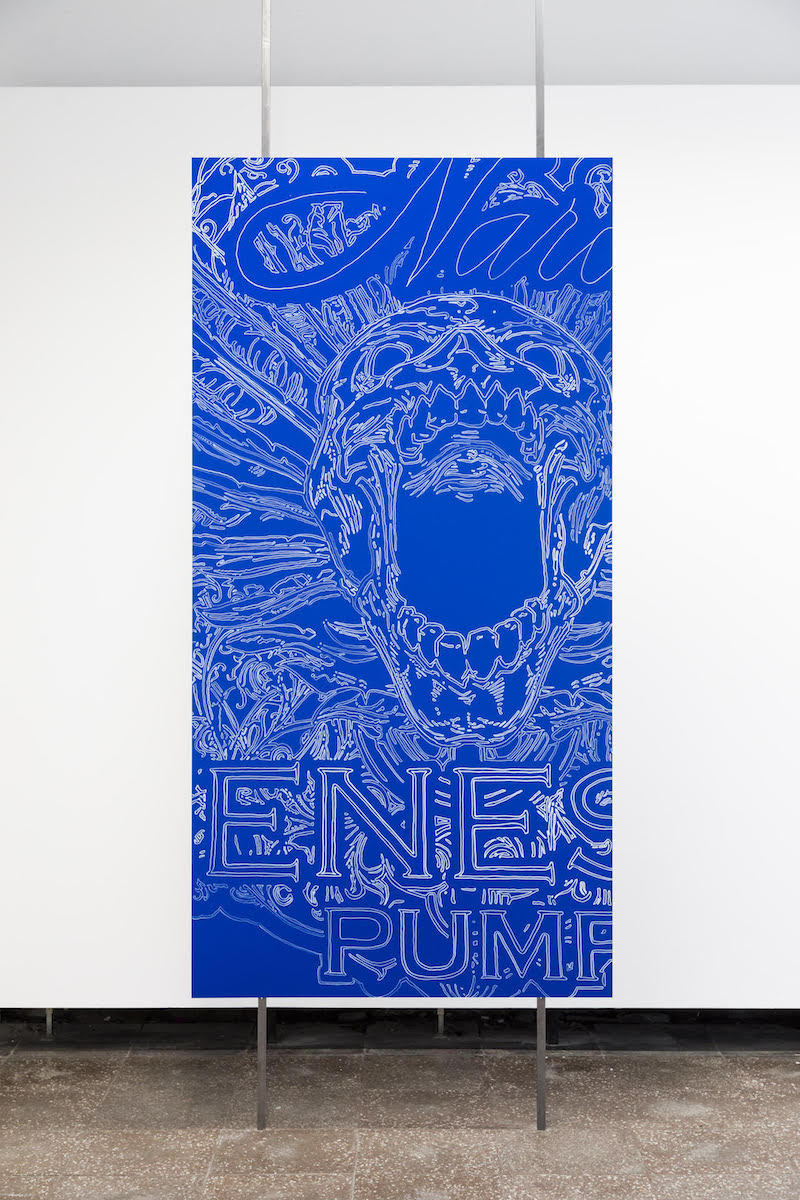

And what is an exhibition about masculinity without a consideration for size? Hartenstein’s four works on display are blue steel plates with hand-drawn white lines, each measuring a formidable 225-by-125 centimeters. They are giant copies of packaging labels of testosterone boosters and protein supplements, and as the title of the exhibition suggests, a man’s virtue is supposedly often measured in his might. Virility is thus desire’s two-way-street: he who embodies it also distributes it. In Hartenstein’s pieces, the oversized labels bleed off the edges of the plates, leaving the viewers to piece together the missing parts. What emerges is a cobbled-together, giant Frankenstein-Adonis, a creature both beautiful and monstrous.

Constantin Hartenstein: ‘Narc Genesis Pump’, 2018, acrylic on steel, 225×125 cm // Photo by Hannes Francke

By comparison, Burford’s works are quieter but speak about transformation and weightiness in a different way. In ‘The Shirt Off Dad’s Back’ (2016), screening in one corner of the gallery, the artist’s mother dresses him in layers upon layers of the worker’s shirts left behind by his late father. At the end of the five-minute video, we see another assembled creature bearing the weight of loss and the inherent heaviness of father-son relationships.

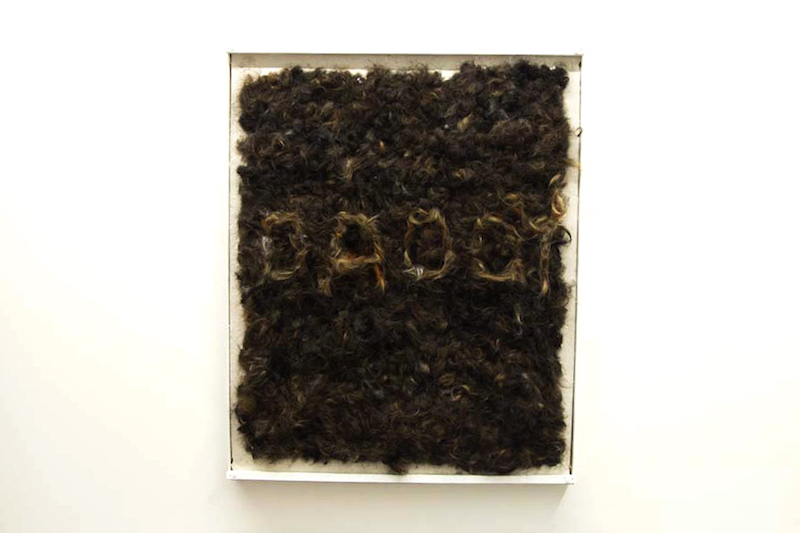

In the opposite corner hangs ‘He Built It With A Limp Wrist (Daddy)’ (2018), also by Burford, a piece composed almost entirely of human hair. The lighter strands stand out amidst the darker curls, spelling out the word “daddy,” a nod to his more biographical piece as well as to “the Daddy” of gay erotic culture. This sardonic juxtaposition of “daddies” elicits a chuckle, but also bespeaks a willful subversion to the normativity of traditional family structures by devalorizing a word and moniker that has held such strong reins over male identity.

Andrew J Burford: ‘He Built It With A Limp Wrist (Daddy)’, 2018, human hair, plaster, chicken wire, wood, 80x100cm // Photo by Hannes Francke

That both Burford and Hartenstein identify as queer is an important part of the exhibition, as they both seem to grapple with a multiplicity of masculinities, stereotypes, and the consequences of inheriting and embodying these complexities. With titles like ‘Cannibal Alpha’ and ‘Alpha Xplode’ (both 2018), Hartenstein’s steel pieces highlight the aggressive, even violent, iconography of the supplements’ labels, which include pictures of fierce animals, confrontational graphics and typefaces that I can only describe as “Ninja-Turtle-masculine.” These products promise an idealized body that is in fact a caricature, prompting the question: if the idealized male form is one who exhibits aggression, and ours is a society in which queer bodies continue to be targets of violence, what are the means to disrupt these expectations? Hartenstein does so with his painstaking mark-making, which in opposition to the images they depict, betrays a conscientious tenderness.

Similarly, Burford’s video collage ‘I’ll Give you Something To Cry About’ (2018), which consists of found footage of crying men, also aims to poke holes in the taut apparatuses that inscribe expectations of masculinity. The chorus line of the 1980 The Cure song ‘Boys Don’t Cry’ plays on repeat, and is at once an assertion, proclamation, admonition and threat. Reminiscent of Bas Jan Ader’s ‘I’m too sad to tell you’ (1970–71), Burford’s piece is a take on the spectacle of male tears in the age of YouTube, and for the viewers, to glimpse cracks in stereotypical masculine fortitude is also to indulge in a perverse craving.

Andrew J Burford: ‘The Shirt Off Dad’s Back’ (screenshot), 2016, video with sound, 05:07 // Photo courtesy of the artist

Taking a cue from Hartenstein’s pieces which resemble architectural blueprints, I approached the works in the exhibition not as necessarily definitive or concrete, but as negotiations, theories, or proposals. I saw ‘Mighty Good Men’ less as an investigation of the complexity and plurality of masculinity, but rather as two artists’ resistance on the forces that control gendered displays of identities. Though as a society a lot more work is still needed to address the troubling ways in which masculinity has been constructed, we get a chance in ‘Mighty Good Men’ to ponder the concept of masculinity in its powers and pitfalls. And by revealing the absurdity and rigidity of masculine identities, the exhibition acknowledges that to talk about masculinity today also means conceding its privileges.

This article is part of our monthly topic of ‘Control’. To read more from this topic, click here.

Exhibition Info

GALERIE IM TURM

Group Show: ‘Mighty Good Men’

Exhibition: May 25 – July 8, 2018

Frankfurter Tor 1, 10243 Berlin, click here for map