Article by Penny Rafferty // July 26, 2018

Cesare Pietroiusti has spent years crafting his unique practice, taking it from the psychotherapist’s office into the white cube. Using glitched adage material over matter, Pietroiusti is best known for making ordinary transactions visible through surreal acts that are, at times, humorous and at others utterly destructive. In doing this he draws attention to and punctures everyday procedures, such as interacting with money or the economy of culture. Yet within his practice, he also always adds a certain tension between his work and both the viewer and art world in general.

Cesare Pietroiusti: untitled (transient possession), 2012

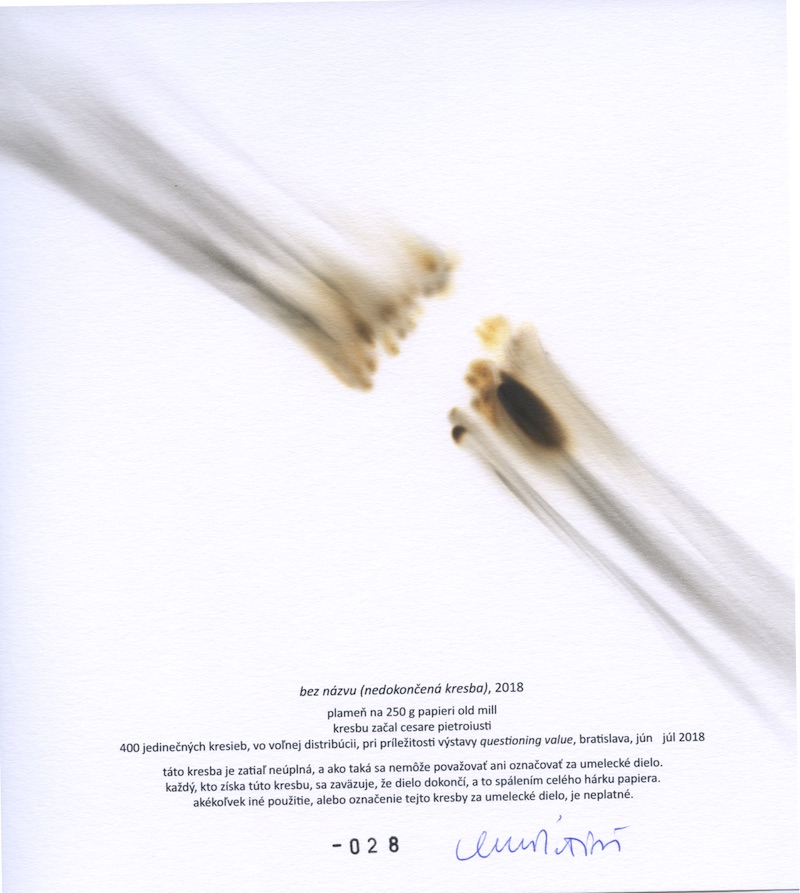

His recent project “Free Distribution of Incomplete Works” (2018), for example, consists of 400 original smoke drawings signed by the artist. The gestures of smoke appear poetic on crisp white paper. Each one is different, bar a printed memo which reads, “This drawing is unfinished, and as such cannot be considered a work of art.” Visitors can take the drawings with them, but in doing so also remove the responsibility of finishing the piece; if they choose to bring home a drawing, the artist requires the entirety of the page to be burned—a task that takes only a minute of their time but is psychologically not so easy to carry out. That quiet moment of “Should I?” is what makes Pietroiusti’s practice so exhilarating, sending shivers down the viewer’s back.

Penny Rafferty caught up with the artist in Rome while he waited for a friend to bring a small piece of a 500 Euro banknote back to him. A week earlier, he had consumed the money as part of another work called Communion and then found in his excrement.

Cesare Pietroiusti: 400 incomplete drawings to be taken for free, 2018, installation view at Gallery Medium, Bratislava

Penny Rafferty: Can we start by looking a little into the history of your practice? I think it’s quite helpful in reading your gestures.

Cesare Pietroiusti: I always say I don’t have a traditional background in art because I studied medicine and was supposed to become a psychiatrist, and I actually did practice for a short while. Because I didn’t have an art education background it helped me to look at techniques and languages with a freedom that one does not have when they are exposed to art schooling.

PR: This is apt in a way because our feature topic for the month is invisibility.

CP: I never really thought about invisibility being a disadvantage or an advantage, but I have always been drawn to the reversion it enables; you can switch between the two states quite fluidly, and use it as a tool. For instance, in the show I have at the moment at Galéria Médium in Bratislava, I am exhibiting and giving away 400 smoke drawings for free, but in order to complete it the viewer must burn the whole sheet of paper. This is the second time I have exhibited the work, previously I even had matches at the end of the gallery. I stood there and offered people the chance to complete the work—only about ten percent did.

PR: So the completion would in fact destroy the material work. I wonder if this has something to do with the personality of said person too. I think I would burn it with you for the rush of the experience, but I’m more drawn to experience rather than material things.

CP: Yes, the act eliminates the aesthetic and visual aspect of the work but opens up the potential for a real experience.The drawings, in general, are quite beautiful, the smoke leaves cloud-like residues across the paper. Yet burning it can also be a moment of absolute pleasure, a rush, and this moment of encounter is just as valuable.

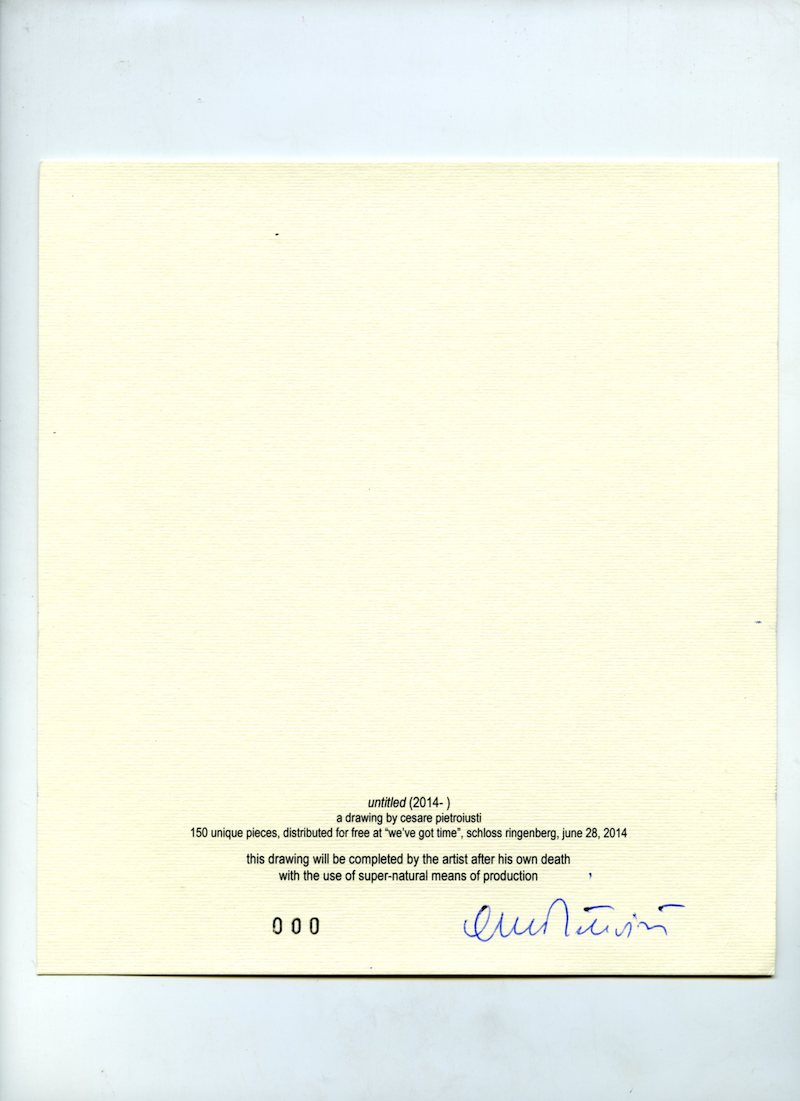

This double bind is what interests me. This work plays between aesthetic beauty and its negation, not one or the other. I find this tension the most compelling space to create from. Another work that explores this is, indisputably for me, my best work. It’s another drawing but it’s only a piece of paper with the printed words: “to be completed after the artist’s death.” Hence the work always makes us think of the performativity of magic, or the idea of gesture after death.

Cesare Pietroiusti: untitled, 2014

PR: To me, this sounds like you’re building in tension, almost like a game mechanic. The viewer can see this beautiful poetic construct of the ghost, but they could also hold a seance for you after your death or find someone to become possessed by you posthumously. This tool of tension is not only frequently found in the performing arts, but also in film and sculpture; I immediately think of works by Richard Sierra and Jose Dávila which manage to manipulate a eternal stationary tension.

CP: Coming from psychology I have always been interested in thought processes, which, in general, often have to do with contradictions. In psychology tension is about force. For example, you can have a certain desire but another part of your mind has an issue with that and therefore you have tension of whether or not to complete the desire. In most cases, this involves sex. Freud had this basic idea of the pleasure principle, which means we are drawn to certain objects and/or actions but are bound up by the reality principle which is, in essence, the consequence of completing the act, and generally this has a social convention wrapped into it.

PR: In regards to your artwork, do you try to manufacture this moment of the “pleasure principle” dilemma?

CP: The artwork does not explore either state fully; it finds the moment in between. It exposes this and at times creates awkward and unconventional situations.

PR: I understand that, but couldn’t we also flip it and say that is, in fact, your pleasure principle as an artist? To personally to create work that makes others feel tension?

CP: Well, yes, certainly, and the personal part is that as an artist, you want to share your own contradictions. Sharing weak points or injured parts of our personalities with others gives a sense of relief. So in a sense, as an artist, you use your own problems to create your profession. You can then create social games, which include contradictions. I don’t know if we could say it’s exactly going towards one’s pleasure principle but it is definitely moving towards a moment of liberation.

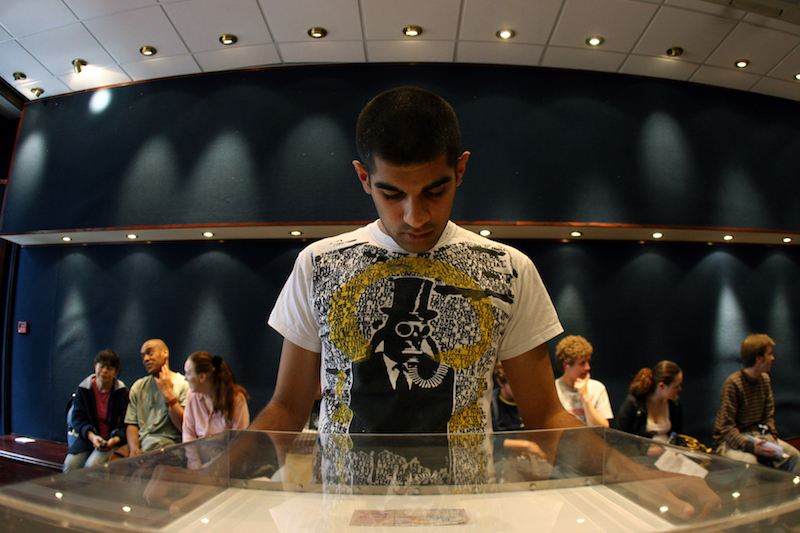

Cesare Pietroiusti: Money-Watching, 2007 // Photo by Chris Keenan, courtesy of Ikon Gallery, Birmingham

PR: Do you have a work that defines these social games for you?

CP: In 2007 I created a work at Ikon Gallery in Birmingham. We had an empty shop front and were selling money, 20 and 50 pound notes. The currency to buy these objects was the customer’s gaze. For example, if you wanted to buy a twenty-pound note you had to queue up and then stare at one side of the note and then the other for twelve minutes. Then the object was yours.

PR: It’s interesting how this is very much a contemporary scenario as far as we watch invisible currency flick across our screens—not in typical banknotes but algorithms and adverts.

CP: A gaze is a tool, and money as an object is simply symbolic. The actuality of money is immaterial. Last week I did a performance entitled Communion with six other people where we dissected and ate a 500 Euro note. Some people said they thought it was a fake note, which also happened in the Church: as the legend goes, one priest who doubted if the bread was really the body of Christ, pulled it apart one day and it bled onto his hands. I enjoy this transcendental aspect. It assures the artworks are always open.

Artist Info

Cesare Pietroiusti: untitled (incomplete drawing), 2018, flame on paper // translation of caption: “drawing begun by cesare pietroiusti / 400 unique drawings, in free distribution this drawing is thus far incomplete and as such it cannot be considered or referred to as a work of art. / anyone who hereafter takes possession of the drawing undertakes that they shall complete the work by burning the entire sheet of paper. any other use, or reference to, this drawing as a work of art is invalid.”