By Isabelle Hore-Thorburn // Sep. 14, 2018

Simon Fujiwara’s best known pieces have drawn on purportedly personal stories, wherein he positions himself as the unscrupulous archeologist of his own history. On entering his first solo show at Esther Schipper, one might expect to be met by characters from the artist’s “supposed youth,” or a little known figure from an obscure historical text. He has previously admitted to a “lifelong problematic relationship with narrative.” In ‘Empathy I’, however, his source materials have shifted from the half-truths of his own history and those of historical textbooks, to the surreal annals of YouTube.

Simon Fujiwara: ‘Empathy I’, 2018, Exhibition View // Courtesy of the artists and Esther Schipper, © Andrea Rossetti

Participants in his ‘sculptural experience’ must meet the height and health restrictions one might find at a Disneyland ride. Fujiwara worked closely with a Sicilian company that produces theme park rides to create his motion ride simulator. The intensely bodily, immersive experience of ‘Empathy I’ is as frenetic as YouTube itself. Composed of ultra-verité videos from the ‘real world,’ the work asks the viewer to reflect on our increasingly simulated culture and its disturbing implications for the cult of the individual.

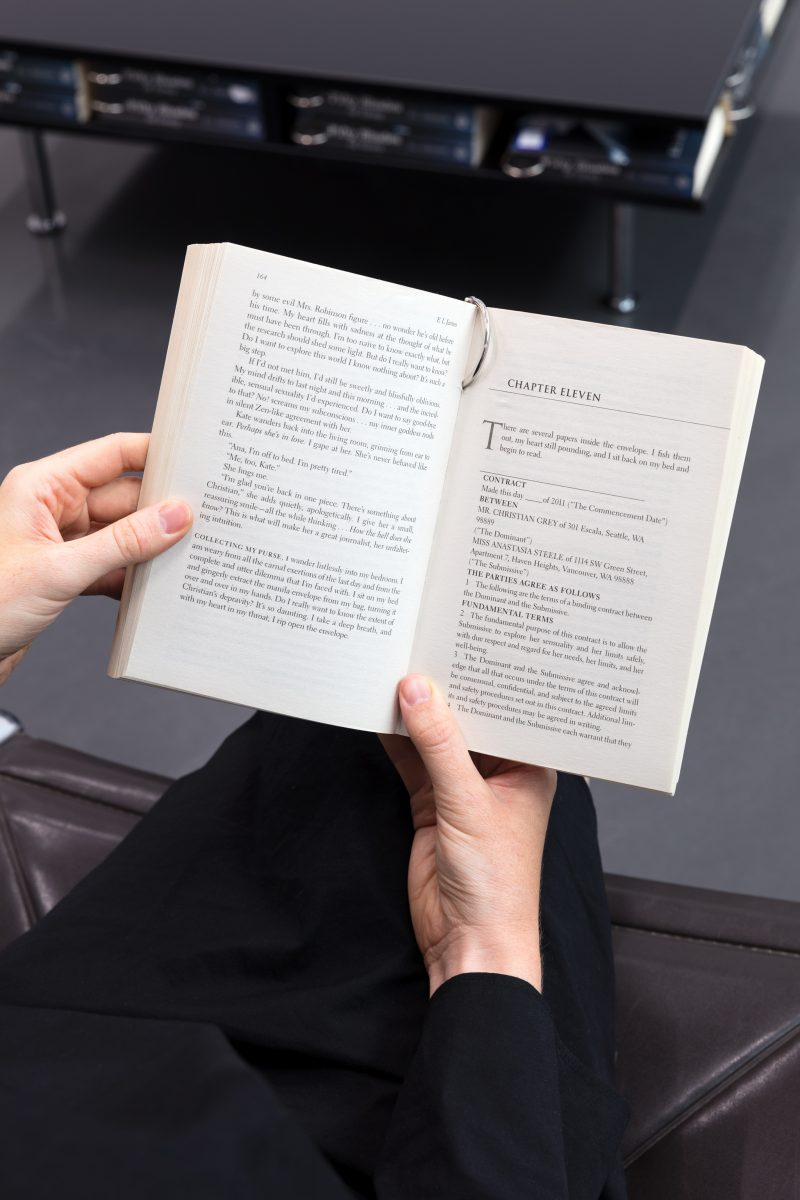

After agreeing to the exhaustive list of safety restrictions, you collect a ticket and wait in the airport-style waiting lounge. The area is complete with Wi-Fi access, a water fountain and several copies of Fifty Shades of Grey. To be clear, there are only copies of Fifty Shades of Grey, as in Fujiwara’s reconstruction of the Anne Frank House at Bregenz Kunsthaus earlier this year. The much maligned erotic novels are each bookmarked at the “contract page”, which stipulates the rules, boundaries, limits, and punishments of a BDSM relationship.

Simon Fujiwara: ‘Empathy I’, 2018, Exhibition View // Courtesy of the artists and Esther Schipper, © Andrea Rossetti

Once your number appears on the screen, you and your co-passenger are ushered into a darkened simulator berth by an officious docent. You must then place your belongings into a plastic tray before strapping yourself into the chair. It is unclear whether this is a metaphorical continuation of the airport scene or the bondage contract.

The film itself is something from the internet of a decade ago; reminiscent of Chris Beckman and Billy Rennekamp’s film oops (2009). Like oops, the footage cuts between appropriated YouTube footage. Within seconds of the ride commencing it becomes apparent that the motion platform seating’s movement is synchronised with the movement of the camera. You are not just watching from the POV of a bride as she walks into her reception, you are physically moved as she is embraced by her relatives; the chair mimicking the gesture of someone hugging and laughing, while Ed Sheeran croons in the background.

Simon Fujiwara: ‘Empathy I’, 2018, Exhibition View // Courtesy of the artists and Esther Schipper, © Andrea Rossetti

The vibrations, elevation and direction of the chair are perfectly orchestrated with a camera crashing through a window and dragging along gravel. You are jolted as the shot cuts to footage of a violent exchange on an American highway. Air is propelled at you as you hurtle through the sky and a perfectly timed spurt of water sprays you as the camera plunges into the ocean.

At certain points, one experiences unnerving empathic connections with the camera person; the wedding scene being the strongest psychological identification. But there are many more instances where the action of the chair, among other theatrical devices, causes a vicarious physical experience with the action of the camera.

Simon Fujiwara: ‘Empathy I’, 2018, Exhibition View // Courtesy of the artists and Esther Schipper, © Andrea Rossetti

It becomes increasingly clear as the three and half minute film progresses, that you may not be empathising with the person behind the camera, as they go through the banal, emotional, and sometimes dangerous experiences of their life. You might, instead, experience a physical connection to the camera itself. As you jolt unsteadily in the air, you are not empathising with a person flying into a hotel window, but a camera attached to a drone, approaching its landing.

As you collect your belongings and make your way out of the simulator—with wet faces and windblown hair—there is an insidious feeling of being taken for a ride, offset by the physical thrill of being taken for an actual ride. We trawl YouTube exactly for the kind of empathetic connection that Empathy I delivers. The realisation of this narrative desire does not, however, fill us with a feeling of connectedness. Instead, Fujiwara skewers our desire for authenticity within an accelerating economy of “personal branding”.

Exhibition Info

ESTHER SCHIPPER

Simon Fujiwara: ‘Empathy I’

Exhibition: Aug. 31 – Sep. 30, 2018

Potsdamer Strasse 81e, 10785 Berlin, click here for map