Article by Isabelle Hore-Thorburn // Oct. 26, 2018

In 1965, the Colombian painter Beatriz González submitted Los Suicidas del Sisga (1965) to the XVII Salon de Artistas Nacionales, where it was initially disregarded by the jury as a “bad Botero.” The painting is today considered an exemplar of modern Latin American painting, yet her desire to “make underdeveloped paintings for underdeveloped countries” and the often polemical nature of her work has produced mixed critical responses in her home country, largely because her works have asked difficult questions about the relationship between institutions, intellectuals and Colombia’s laboring masses during periods of extreme social tension. González’s exploration of “lo popular” (the low brow) and “lo cursi” (the tacky) and her contestation of the boundaries of good and bad taste have come to define her career, and pervade the survey show of her works on now at KW Institute for Contemporary Art.

Beatriz González: Los suicidas del Sisga No 2, 1965 // Courtesy Courtesy of Künstlerin, Óscar Monsalve and Museo La Tertulia, Cali, Sammlung Museo La Tertulia, Cali

The art critic and writer, Marta Traba, insisted on the consideration of Los suicidas del Sisga and the painting went on to win a special prize. The work was, however, described as “lo cursi” in the Bogotánian newspaper, ‘El Tiempo’; purportedly emblematic of a “crisis in the Salon” and representing a “spectacle of fraud.” The anxiety elicited by the painting–from the press and the academy—reveals an ideological tension between the gatekeepers of Colombian institutions and women, “el pueblo,” and those from the provinces, during a period when the devoutly Catholic country was undergoing accelerated modernization. The invocation of “lo cursi” in reference to the painting, is used in the pejorative sense to describe how González’ work introduced a distinctly “low brow” aesthetic into Colombian art. Beginning with Los suicidas del Sisga and continuing throughout her career, González explores “lo popular” to reveal how the idea of taste is used as a form of social exclusion.

It makes sense that Los suicidas del Sisga is one of the first paintings in the first room of the exhibition. The painting was inspired by an image of a young couple González saw in a local newspaper. In 2015, she told the Tate: “the man, guided by mystical insanity, convinced his girlfriend to commit suicide in order to preserve the purity of their love. Before jumping from the dam of the Sisga on the outskirts of Bogotá, the couple commissioned a professional photographer to take their portrait.” As well as being one of her most recognizable paintings, the work marks her transition from traditional painting into the flattened, chromatic images of appropriated press clippings that have positioned her as a Pop artist.

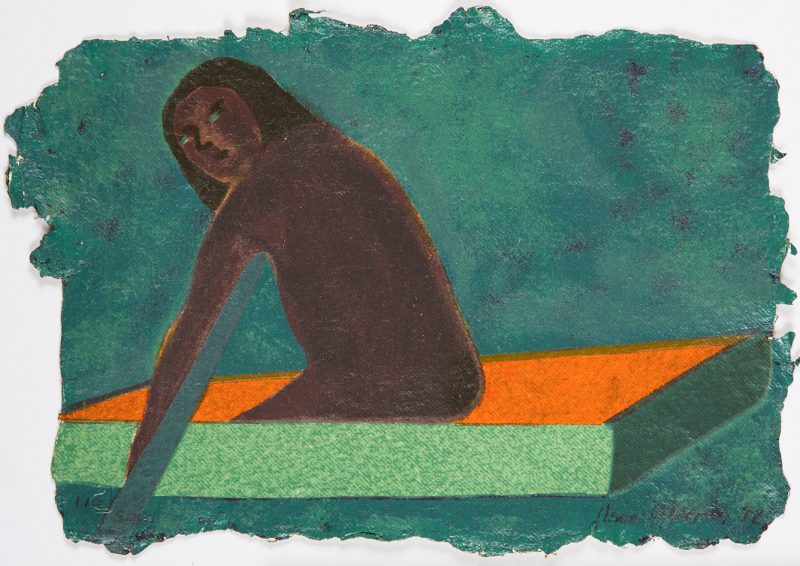

Beatriz González: 1/500, 1992 // Courtesy the artist

We must be cautious, however, when ascribing González with the title “Pop artist” or framing her work as a provincial response to an international trend. While she has been included in blockbuster exhibitions like ‘The World Goes Pop’ at Tate Modern, González has repeatedly stipulated “Yo NO Soy Una Pintora Pop” (as in her 1997 lecture of the same title). Marta Traba suggested that “the conditions for pop’s existence didn’t exist, mainly because we didn’t have a consumer society on the scale of other nations.” González explains that her furniture pieces, for example, which famously used cheap materials to depict sacred figures or European masterpieces, were “a reflection on taste” rather than an expression of consumer culture.

As we progress through the rooms of the exhibition, just as González progressed in her own career, we see a shift in concept and colour, towards a more violent and dark rendering of life in Colombia. The 1985 M-19 attack on the Palace of Justice, which left 94 dead, was a catalyst for this shift; “My art changed then, I felt that we couldn’t laugh anymore. I started to explore themes of death, the drug trade…The colours changed too.” While González continued to appropriate press images, like gossip columns and advertisements, the political dimension of her work became more explicit.

Beatriz González: Decoración de Interiores, 1981 // Courtesy KW Institute, photo by Frank Sperling

By making her focus the provincial everyday reality of Colombians, González does not present a coherent thesis on their history, instead her work articulates the futility of violence as it touches Colombians from oppugnant corners, from drug lords, paramilitaries and neighbours. Yet, as in life, tragedy and violence sit alongside joy and the absurd. In a 1978 television interview, González explained “mi trabajo es Pasaje Rivas,” referring to the “tasteless” and often illicit marketplace of Bogotá. The humour and violence of González’ work seem not to belong to the academy or the institution, but to the everyday spaces of “el pueblo.”

Exhibition Info

KW INTSTITUTE

Beatriz González: ‘Retrospective 1965–2017′

Exhibition: Oct. 13, 2018–Jan. 06, 2019

Curator’s tour with Krist Gruijthuijsen: Dec. 13, 2018; 7pm

Assistant curator’s tour with Cathrin Mayer: Nov. 22, 2018; 7pm

Auguststraße 69, 10117 Berlin, click here for map

Colombian Film Afternoon

KW INTSTITUTE

2 films selected by Beatriz González (Spanish with english subtitles): Dec. 02, 2018; 5pm, 7pm

Studio at KW’s front house, Auguststraße 69, 10117 Berlin, click here for map