Interview by Lucia Longhi // Mar. 01, 2019

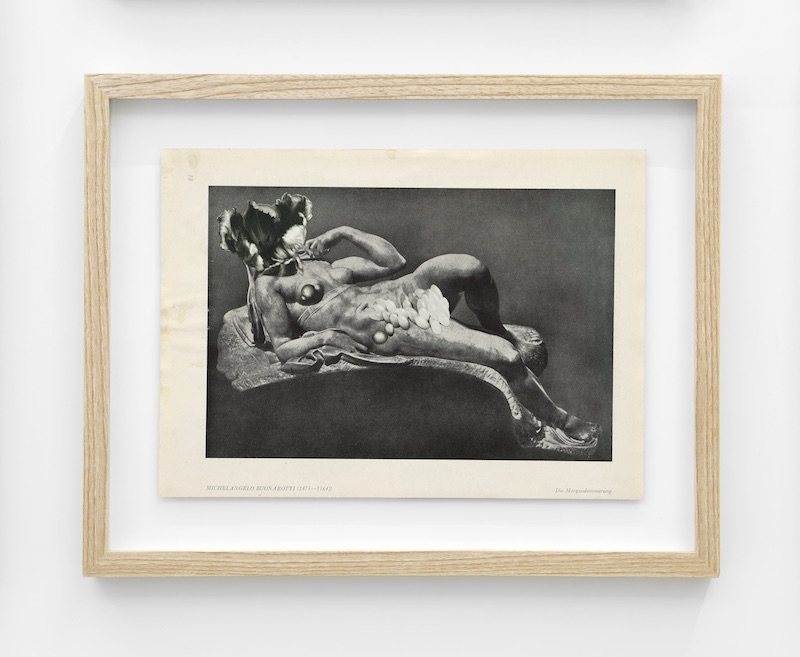

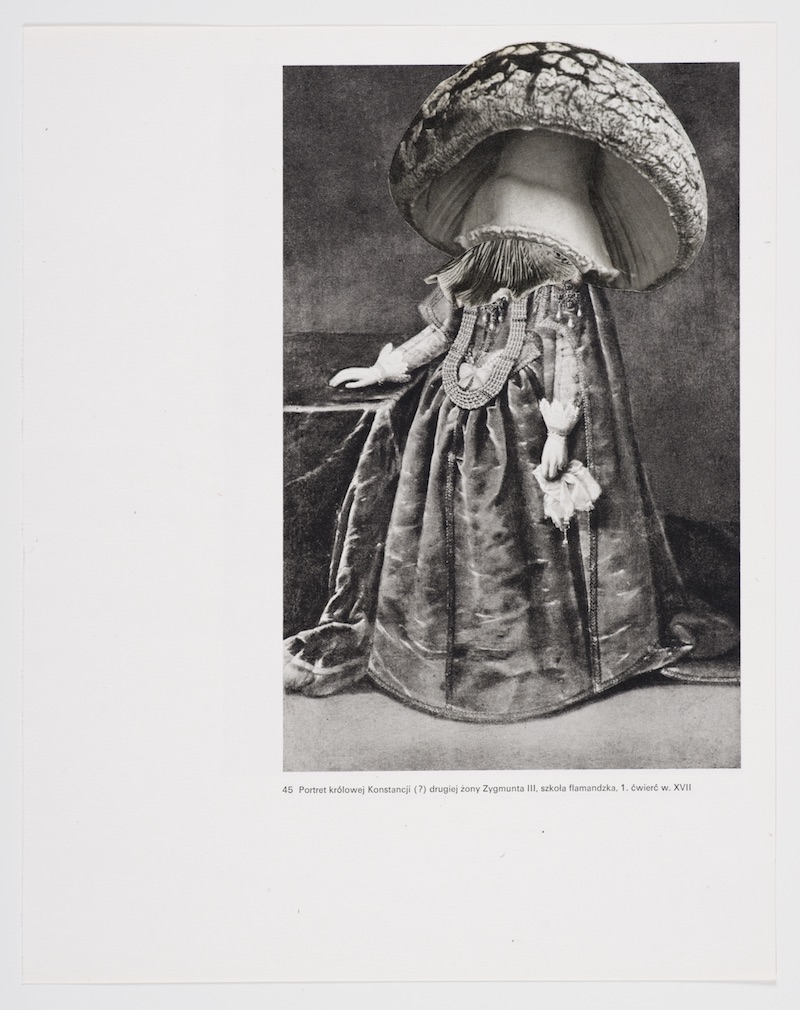

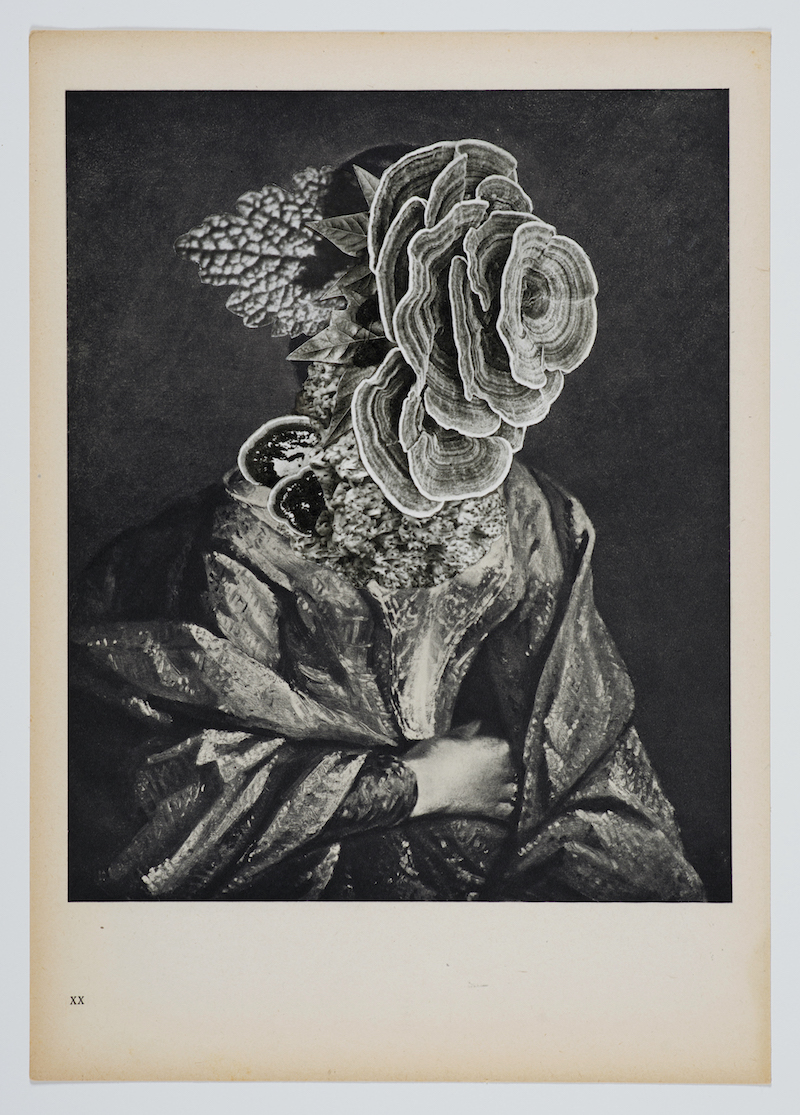

Ewa Juszkiewicz’s work stems from a substantial failure in the history of art: the portrayal of women. Rather than the depiction of a person, portraits of women – especially in the Renaissance – were a composition of aesthetic and social canons, resulting in figures that were ultimately just anonymous objects of beauty, perfection and deference. The Polish artist aims to dismantle the old paradigms that hid a woman’s personality, claiming and visualizing a new role for them. She replaces their faces with new symbolic features like natural elements, fabrics or locks of hair. Mysterious masks recall ambiguous emotions, thus reversing the classical order of the painting and bringing it to a non-rational level of perception.

Masks have always meant freedom of expression. The artist attempts to rectify that old failure in history, inviting us to reexamine these women and their positions. By deconstructing the original painting, she deconstructs the conventions behind it, building a connection between the past and the present and forcing us to think about those modern corsets that restrain women today. The process of reproducing an old painting also allows Juszkiewicz to put herself in the role of the old painter, identifying with him and deeply understanding his position and practice.

Ewa Juszkiewicz, portrait in the studio // Photo by Adam Gut, Courtesy of the Artist and Galerie Rolando Anselmi

Lucia Longhi: Your work stems from what we could call a failure: the unfortunate outcome of the female image in the history of art. I see your work as an attempt to reclaim, as if you’re trying to correct and rectify this failed vision in history. When and how did you become aware of this failure in classical portrayal?

Ewa Juszkiewicz: I have been dealing with the female image, as well as analysing and researching how it has been shaped over the centuries. Observing these classical representations in European painting, I noticed that all the women portrayed are actually very similar to each other; they strike similar poses and make identical gestures. Looking at them, I often got the impression that they were trapped in corsets, crinolines, layers of petticoats constraining their movements, somehow imposing their presence on them in the world. Fashion in the past is visually attractive and fascinating to us today but, upon deeper reflection, we can conclude that its hidden function is a kind of oppression and constraint. There is not much room for individuality or otherness. What is significant is that this also applies to contemporary canons of beauty and ideals of the female body. I think it is a bit like making fun of history. We consider ourselves to be more modern than our ancestors, but we actually squeeze ourselves into our own, modern ‘corsets’. My painting is the result of a little bit of contrariness; a desire to break free from the norms imposed on us by our fashion and culture.

Ewa Juszkiewicz: ‘Untitled (After Joseph Wright)’, 2019 // Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Rolando Anselmi

LL: So disagreement, but not only this. I see somewhat of an identity claim: is your intention to create a new identity for the portrayed figure? Is your practice more about removing or creating? What are the criteria on which you chose the paintings you want to recreate?

EJ: When looking for inspiration for my paintings, I first of all look for works that are full of the conventions I mentioned. I look through old albums and art books, and try to find portraits in them that cause me to feel something – ones that fascinate or move me. It would seem that the emotions they evoke are very important here because they allow for some kind of symbolic demolition of the canon these works represent. By taking something from them, destroying their original subject matter in a certain way, I build something new, I tell my own story. However, I don’t want it to sound like I’m creating new, historically-artificial creatures, because I don’t give my female characters a new identity through these changes, but I want to express the emotions the past evokes in me. By analysing it, transforming the past, I try to start a dialogue about the modern day and broaden our interpretation of the past through these changes and deconstructions. Paradoxically, covering the characters triggers an avalanche of questions. We start to ask ourselves: “Why did that happen? Is there anything hidden under this layer?” This metaphor of covering up their faces is, in fact, a revelation and an attempt to build on the subjectivity of these characters. I think the mask allows us to say more, because it frees us from the conventions we have adhered to all our lives.

Ewa Juszkiewicz: ‘Untitled’, 2017 // Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Rolando Anselmi

Ewa Juszkiewicz: ‘Pearl, Eye, Worm’ show at Galerie Rolando Anselmi, Rome, 2017, Exhibition view // Courtesy of the Artist and Galerie Rolando Anselmi

LL: You question the idea of beauty. Is this the reason why many of your works are, in a way, disturbing? I’m thinking of the paintings with insects or fungi, for example.

EJ: When analysing European culture and history, it is very easy to see that it was based on dichotomy: culture – nature, reason – feelings. The old world was polarized this way and the echoes of this reasoning are still felt today. By replacing that which is ‘classical’ – that is, that which is subject to the dictates of certain canons and norms – with what comes from nature, I am overturning a certain eternal order. Nature has always aroused uncontrollable feelings of joy through fear and anxiety. That is why on the faces in my paintings you see insects, fungi, plants, tangled strands of fabric and thick locks of hair. These elements stir up emotions in us because they lie on the edge of the rational world. I have always been interested in contrasts, contradictions, seemingly incompatible juxtapositions, because, in fact, thanks to them, we can see more and look much deeper. We stop drifting along the surface of reality.

Ewa Juszkiewicz: ’45’, 2017 // Courtesy of the Artist and Galerie Rolando Anselmi

LL: You use objects of all sorts to replace the faces of the women: hair, draperies, natural elements. Is there a connection between the identity of the original woman portrayed – her personal history – and the object you choose to replace her face?

EJ: Due to the fact that history as we know it today was written and often dominated by men, we often know very little about these ladies in such portraits, or just whose wife, mother, or daughter they were. Their presence is justified by the existence of a man in the past who shaped and had an influence on the time in which he lived. When I am creating my paintings, I am not guided by the history of the original or the portrayed woman. The important thing for me is what the painting itself shows: it is the first impression, what I am able to get from it today. The changes that occur as a result of this visual analysis are dictated not only by the painting itself but also by the associations that appear when looking at it; the clothes of the characters, the hairstyle, the body language – sometimes even a tiny detail in the background, such as a bouquet of flowers or an unruly strand of hair or the draping of a gown.

Ewa Juszkiewicz: ‘Untitled’, 2018 // Courtesy of the Artist and Galerie Rolando Anselmi

LL: Failure is present in your work not only as the origin of your practice, as we said before, but also in the process. Your paintings are created on the basis of a process of deconstruction and denial, like when you disassemble an object because the first version was wrong or damaged. Your practice is also about reworking.

EJ: Classical art has always been based on certain principles of composition. These restrictions also influenced the way the characters were depicted. Paintings from the past are full of patterns and archetypes that were reproduced, either in the poses adopted by the model, or the position of his or her palms and facial expressions. The painting was supposed to accentuate the best features of the person portrayed, and it is known that in the case of women it was often modesty, subtlety or submissiveness. I think the statement that the original was bad is not quite correct in this case. In this way, and in only this way, a narrative in the painting would be created and built. In my work, I try to break this old order and overturn this old convention by disturbing and destroying the primary matter of the painting. While preserving the technique of the original, I transform and deconstruct it. I think that my actions result primarily from my disagreement with the existing pattern, from an attempt to tell a new tale, to write a new story, or an attempt to give a new voice to someone who lost theirs.

Ewa Juszkiewicz: ‘Untitled (Bones)’, 2018 // Courtesy of the Artist and Galerie Rolando Anselmi

LL: Part of your practice involves erasure but, at the same time, there is a faithful recreation of other parts of the original image. What does it mean to you, to identify with the painter?

EJ: Referring back to the original, certain parts are taken away, transformed and, in other parts of the painting, I try to follow the brushstrokes of the artist faithfully, preserving the style and character of the original. For me, this activity is a symbolic attempt of forging a relationship with a painter from the past. In this way, I try to establish a dialogue with him and try to share the common experience that is characteristic of creative work. It is a little bit like a séance: a painterly attempt to look for connections, to recall the presence of the painter from the past and to say just that little bit more, maybe what has been hidden under the painting for all those years?

This article is part of our monthly topic of ‘Failure.’ To read more from this topic, click here.

Artist Info

Ewa Juszkiewicz: ‘XX’, 2017 // Courtesy of the Artist and Galerie Rolando Anselmi