Article by Johanna Hardt // Mar. 15, 2019

The film Prison Architect (2018) by Cao Fei uses the physical space of the prison as a metaphorical complex to reflect common understandings of freedom and captivity. More than presenting the prison as an actual site of criminal punishment or misuse of power, the film questions how we live with the idea of the imprisonment of fellow human beings – imprisonment in an actual cell as well as in spaces that give the illusion of allowing human agency.

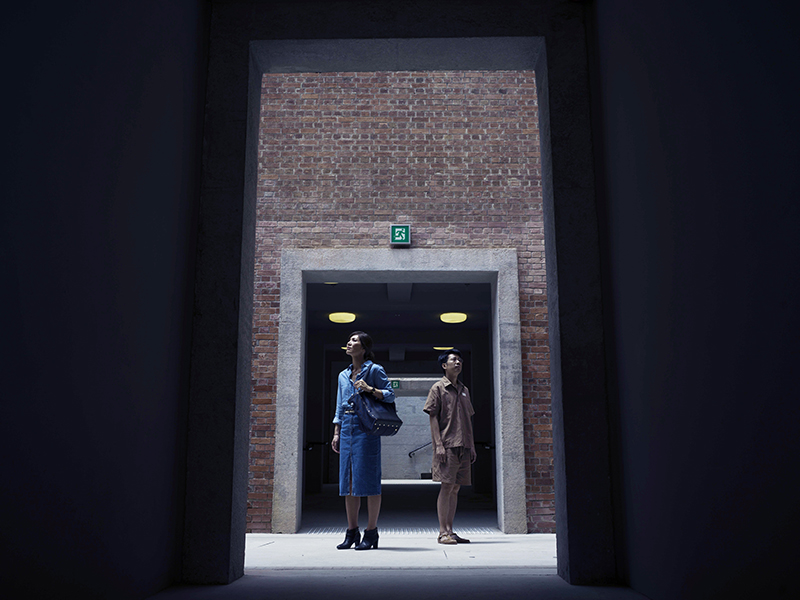

Cao Fei: Prison Architect, 2018, video still // Courtesy of Tai Kwun, cinematography by Kwan Pun Leung

Commissioned by Tai Kwun, the Centre for Heritage and Arts in Hong Kong, the film addresses the history of the place that is now home to contemporary art. Located in what was the city’s first and longest-running prison complex, Tai Kwun occupies the former Victoria Prison, which was built under British colonial rule. Whilst in the case of Tai Kwun a prison has been transformed into an arts institution, Prison Architect reverses the event: A contemporary female architect is tasked with transforming a centre for art and culture into a prison. The person that questions the ethics of her task is a contemporary female architect. Questioning the ethics of the task at hand, she suffers from the idea of herself “becoming someone who designs spaces to imprison fellow human beings.” The audience follows her thoughts as they unfold as poetic dialogue between herself and a former prisoner.

Cao, known for her interest in world-building, alternative realities and the integration of tradition into a contemporary practice, stretches the dialogue between temporalities and realities, ultimately allowing for a reflection on the building’s past, present and future. First screened at her solo exhibition at Tai Kwun in 2018, Prison Architect was screened earlier this year in Berlin as part of the Berlinale Forum Expanded.

Johanna Hardt: Prison Architect engages directly with the dense history of Tai Kwun. How did you approach the past of this building?

Cao Fei: I visited Tai Kwun repeatedly in the past three years before it opened to the public. At the beginning, I didn’t know what Tai Kwun was—it was just a construction site—but after that, I went there twice a year and observed the changes. The ending of Prison Architect mentions how it was inspired by a novel by Hu Fang. Even though I only read the story last year, it affected the direction of the film. As time went on, my ideas about the movie and the exhibition changed, and this included me changing, too. Talking with the curator altered my understanding of the project and when I started working on it, Tai Kwun was still in the process of construction so I was able to read about its history. There was enough time and organic growth to allow for the work and ideas to mature.

Cao Fei: Prison Architect, 2018, video still // Courtesy of Tai Kwun, cinematography by Kwan Pun Leung

JH: The film was first screened as part of your solo show ‘A Hallow In A World Too Full’. Can you speak about the architecture of the building and in what sense you engaged with it for the exhibition as well as the film?

CF: I wanted to keep the artworks alive, not engulfed by the space. I took special care, thinking in detail about the space and the installations, doing things I had rarely done in the past, like adding moss on the walls and the rough texture of the cement, and considering people’s performance. These details break through the traditional presuppositions of a cultural platform for visitors while they walk through and view the exhibition, letting them forget the textures and the rarefied nature of a structure. Some walls featured in the film are designed as a response to the venue, to keep reminding you about the histories inside the walls.

Cao Fei: Prison Architect, 2018, video still // Courtesy of Tai Kwun, cinematography by Kwan Pun Leung

JH: The scope of the production is quite impressive. Whom did you decide to involve?

CF: I told Tai Kwun from the get-go that if we were to film Prison Architect in Hong Kong, we should ideally work with a local production team. For photography, one of my friends suggested the local cinematographer Kwan Pun Leung (Director of Photography for the Wong Kar-wai film 2046). The main actress, Valerie Chow, who plays the architect in the movie, acted in Wong Kar-wai’s film Chungking Express in 1994 and is a friend of a friend. As a retired actress, I assume she would have said no, had Prison Architect been a commercial movie. But this is a special work of art, which will be shown in galleries and Tai Kwun is such a distinctive historical site, so everyone naturally was interested. I had never directly met the artist Kwan Sheung Chi, who played the prisoner, before filming, but I’ve had my eyes on his contemporary artworks for a long time. I needed someone with a literary air, one with hidden bitterness and misery to portray the imprisoned poet.

JH: One central narrative of the film is the architect’s ethical concerns about designing a system of control, a system that monitors and dictates behaviour. The prison has been discussed and theorised as a symbol of a disciplinary society of surveillance. Can you speak about what the film seeks to convey in terms of the relation between the museum and the prison?

CF: This is not a work about a physical prison; it is trying to explore a much broader condition of imprisonment inside our minds. For instance, the earth is much like a huge jail. We could also say that the entire galaxy is a vast prison as well. We can’t escape from those places, we can’t “fly away”. As individuals, this causes us to question our meaning and position in this world, this “prison”. That’s an important concept and it’s what Prison Architect gets the audience thinking about. The concept of the “prison” is macroscopic, omnipresent, like our work and lives in a contemporary metropolis with nine-to-seven (or later) jobs. Such living patterns can be a certain form of imprisonment.

Cao Fei: Prison Architect, 2018, video still // Courtesy of Tai Kwun, cinematography by Kwan Pun Leung

JH: Would you say the film formulates its own philosophy of freedom?

CF: The concepts of freedom and imprisonment inside the film are abstract. They do not in themselves directly refer to something in history nor to the spiritual reformation of a specific imprisonment. The prison architect in the movie may not even be a real architect, but rather a messenger who has come to liberate souls. The work encourages audiences to rethink the concept of imprisonment through the character set-up and the prison design. Although the prisoner is trapped physically, she (the prison architect) still can sense what the poet experienced in captivity, thus enlightening the self to transcend on a spiritual level all kinds of “imprisonment” by various sorts of reality. The work is subjective and free, I allow for encounters. Films can allow the narrative to go off-track and allow reality to seep in—even if this process of encounter is on the spiritual level, the level of the soul.