Article by Sarah Messerschmidt // Mar. 22, 2019

“The evolution of Conceptual Art overlapped with the end of the gold standard in the USA in 1971, and since then, the entwinement of art and finance has become evermore abstracted,” or at least so writes Lucie Fontaine, the purported curator of ‘₡ U R ₹ € ₦ ₢ ¥’ on show at NOME Gallery in Berlin. The relationship between art and money is not a new subject, and certainly visual art has long been known to ride on the coattails of financial power. Yet the dizzying acceleration of the art market in recent decades has pushed the question of art and commerce to the forefront of artistic interrogation, such that economic power structures are at once challenged and reinforced by the activities of visual artists.

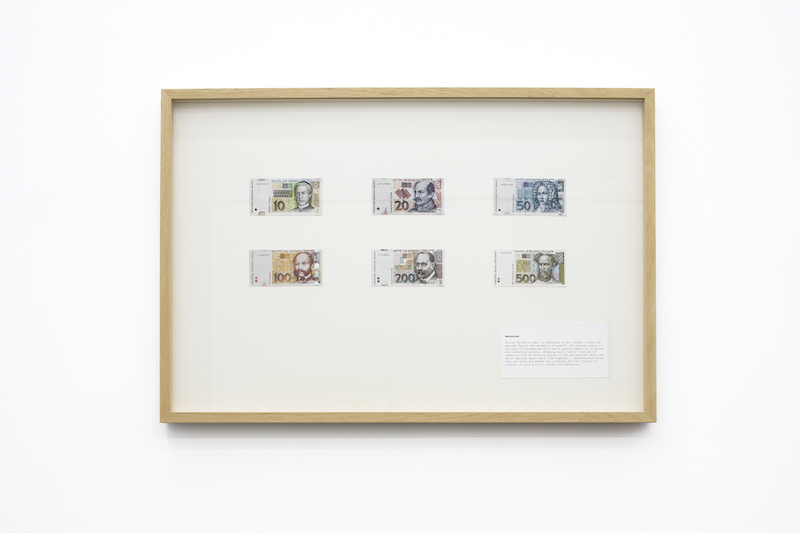

Igor Grubić: Banknotes from the series “366 Liberation Rituals”, 2008–09, mixed media, 63×92.8×3 cm // Photo courtesy NOME Berlin

The group exhibition ‘₡ U R ₹ € ₦ ₢ ¥’ addresses these imbalances of power, honing in on both monetary and non-monetary systems of exchange. In her accompanying essay, Fontaine cites a “bond between the behaviour of money and the behaviour of visual art”, suggesting that since at least the 1970s, conceptual art has paradoxically concerned itself with interrogating how art is valued, while simultaneously participating in a rapidly developing art market. The show at NOME takes a deeper look at this, using the broadest notion of currency as its point of departure; as Fontaine writes, the flow, or “current”, along which art and money move is the agent that binds the exhibition. The show brings together a vast range of work, including drawings, sculptures, video works and more conceptual installations, and perhaps a pertinent place to begin is with Igor Grubić’s Banknotes from the series “366 Liberation Rituals” (2008–09). The work, which features six framed banknotes on which Grubić has inscribed “Resist the epidemics of greed!” in his native Croatian, is the end result of a year-long “intervention” staged by the artist himself. Every day for one year, Grubić marked and disseminated 1,300 bank notes with this message in the hope that his action would somehow intervene in the consumerist habits of Croatians, whom he observed “spending more money than they earned,” in the capitalist deluge that overcame Croatia during its transition from socialism.

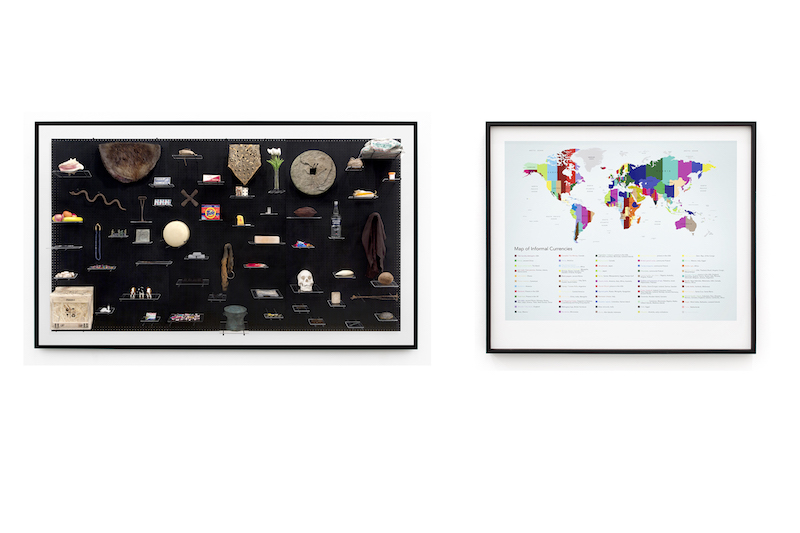

Agnieszka Kurant: Currency Converter, 2019, UV print on plexiglas with aluminium mount (photo); pigment print on archival paper (map), 95.9×137.5 cm (overall); 95.9×117.2 cm (framed map) // Photo courtesy NOME Berlin

Next to Grubić’s piece hangs Agnieszka Kurant’s Currency Converter (2018), which consists of two images: a picture of a shelving unit on which sit seemingly unrelated objects, and a corresponding map of how these objects have been used globally as informal currencies. The work traces a history of the circulation of objects as money from antiquity to the present day, and included in its index are Tootsie Rolls and other sweets, exchanged in Argentina, colourful wrappers in communist Poland, fresh fruit in US prisons, mirrors in Egypt, and rice in Japan. The work cleverly indicates the real use value of objects, which vary depending on region or era, as well as the social, economic and/or political realities of the places the objects represent. A window into money-less systems of exchange.

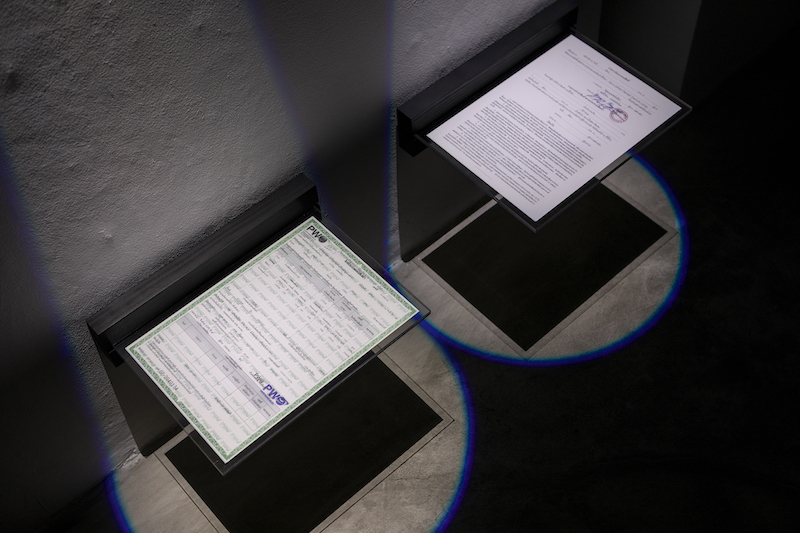

Pratchaya Phinthong: Untitled (rice), 2014, A4 document in Thai under plexiglass sheet // Photo courtesy NOME Berlin

In a different vein, Pratchaya Phinthong’s Untitled (rice) from 2014 examines another type of unorthodox currency, making reference to the “Rice Pledging Scheme” in Thailand. This was a mortgaging strategy, implemented by the Thai government in 2013, which encouraged rice farmers to consign harvested rice in exchange for mortgage papers. Shortly thereafter, Thai rice prices in the global market plummeted, and the then-government became unable to repay mortgages, leaving millions of farmers in precarious economic positions. Phinthong’s work, two illuminated consignment papers mounted at ankle-level beneath plexiglass, is an austere reminder of the effects of government corruption, and might be understood as a call for transparency in economic policy-making.

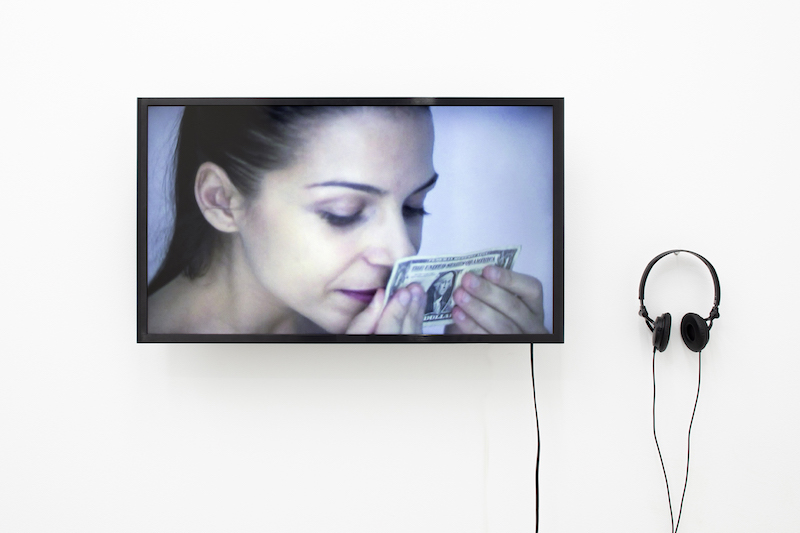

Ana Prvački: At the Tips of Your Fingertips (towards a clean money culture), 2007, video, 01:39 minutes // Photo courtesy NOME Berlin

In the adjoining room screens Ana Prvački’s 2007 video At the Tips of Your Fingertips (towards a clean money culture). Playing with the concept of “dirty money”, the work is a farcical informercial advertising “Money Laundering Wet Wipes”, designed specially for the sanitisation of bacteria-ridden bank notes. As a parody on laundered money (Prvački’s proffering of “clean money” sits in direct opposition to Fontaine’s allusion to shadow economies), dirty versus clean is not the only quirk in this piece. As Prvački explains, though money is the most widely circulated surface on earth, it cannot be altered physically. While the artist developed a sanitation product to ritualistically clean bank notes by hand, ensuring the physical properties of each note is unchanged with its cleansing, her efforts are immediately negated once the sanitised bank notes are again in circulation. Prvački writes, “the poetry of the piece lies in the sheer absurdity of the endeavour.”

Jan Tichy: History of Painting II., mixed media on forty 35-mm colour diapositives from the discarded diapositives collection of the Art Institute of Chicago displayed on a slide projector on continuous loop, variable dimensions // Photo courtesy NOME Berlin

From Miri Segal’s The New 25 (2019) to David Rickard’s Stolen Pound (2018) to Slavs and Tatars’ When in Rome (2010) and Marco Cassani’s Fountain (Gunung Kawi) (2017), so many of the works on display in ‘₡ U R ₹ € ₦ ₢ ¥’ consider various interpretations of the titular term, examining the flow and circulation of “money as a channel, money as a concept, and money as a formal (or informal) structure.” With what turns out to be a fictional character at the helm of the exhibition’s production—like a shadow economy, the invention of Fontaine’s own presence in the show hints at a non-compliance with a set of (art) institutional rules—the concept of currency is altered, twisted and challenged. Indeed, the exhibition at large resists the axiom that money is the only legitimate means of designating value, and invites its audience to reconsider systems of exchange and systems of value, leaving one wondering if the cultural currency of the artist is yet another means of establishing value in an economically-driven society.

Exhibition Info

NOME BERLIN

Group Show: ‘₡ U R ₹ € ₦ ₢ ¥’

Exhibition: Mar. 02–Apr. 19, 2019

Glogauer Straße 17, 10999 Berlin, click here for map