Article by Johanna Hardt // May 02, 2019

Regina Silveira, considered to be one of the most influential Latin American artists of her generation, spent most of her life in São Paulo, Brazil’s most populated city. She graduated from visual arts in her native town of Porto Alegre, where she studied with the famous Brazilian expressionist painter Iberê Camargo. In the 1970s, Silveira started experimenting with photographic imagery in response to the hostile political environment under military dictatorship. Creating conceptual works such as videos, pamphlets and prints, she soon became an active participant in Latin America’s mail-art circuits. Her work explores the tension between movement and perspective, between absence and presence, while parodying geometric constructions and often responding to specific sites.

‘The Power of Reproduction,’ 2019, installation view // Image by WaltherLeKon

Having exhibited on an international scale, she recently participated in the group exhibition ‘The Power of Reproduction – From pre-digital to post-digital reproducible art, or from engraving to Xerox to Augmented Reality in South America and Germany’—a project developed by the Goethe-Institut in collaboration with Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul and other partners. As a dialogical project between Brazil and Germany, the exhibition took place in Leipzig throughout March and opened up questions regarding the political and societal impact of reproduction processes under the conditions of digitalisation. It brought together 14 different German and Brazilian artists, including Vera Chaves Barcello, Tim Berresheim, Marcelo Chardosim, Hélio Fervenza, Hanna Hennenkemper, Olaf Holzapfel, Helena Kanaan, Thomas Kilpper, Flavya Mutran, Carlos Vergara, Ottjörg A.C., XADALU, Rafael Pagatini and Regina Silveira, who spoke with me about her specific use of reproduction techniques and the power she assigns to this practice.

Johanna Hardt: The so-called printing clubs founded in the 1950s by various artists in Rio Grande do Sul and its provincial capital Porto Alegre have formed the most important centres of reproductive art in Brazil. What is your relation to these clubs? Did their existence shape your own engagement with the way you are (re-)producing?

Regina Silveira: My engagement with printmaking did not arise from that source and I was not influenced by that group – since I studied printmaking at the Atelier Livre (Open Workshop, Prefecture of Porto Alegre) with the artists Francisco Stockinger and Marcelo Grassmann, who had a different approach and background. Francisco Stockinger, a sculptor, had been a disciple of Oswaldo Goeldi; and Marcelo Grassman, essentially a printmaker, was developing an oeuvre of a markedly expressionist character. I also think I was influenced by the printmaking of Ibere Camargo, with whom I had painting classes, for many years. At that time, the Arts Institute of the Universidade do Rio Grande do Sul, where I received my bachelor’s degree, did not teach printmaking, as it was considered a lesser art. I must say that at that time I considered the production of the Printing Club very backward and traditionalist. I wanted to take other directions. Later, I was able to better evaluate its historical importance.

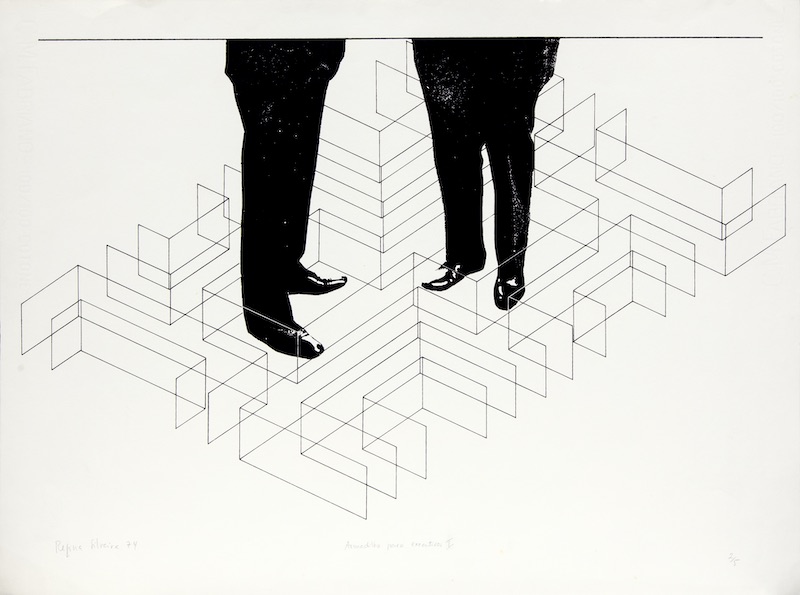

Regina Silveira: ‘Armadilha para executivo I,’ 1974 Screenprint on paper, 52 x 70 cm // Courtesy of the artist

JH: In your work, reproduction functions as a means of communication rather than a strategy for producing more works and reaching larger audiences. What makes you interested in this technique in the first place and what kind of reproduction methods do we find in the works selected for the exhibition?

RS: I never believed in the supposedly democratic role of reproduction with large print runs for large audiences, at low prices. This equation depends on the repertoire, on who makes and who receives—art itself has never been democratic. I understand that the transformative role of the printed image depends much more on the modes of circulation.

I can list the types of reproduction that are present in this exhibition: silkscreen, digital printing and photo-etching. I think they all include photomechanical resources, for operations of the appropriation of printed media. But I must say that these are only a small part of what has been an enormous variety of both traditional and industrial uses of graphic media since the 1970s, when I was characterized as a “multimedia artist.” This is explained by my permanent and nonhierarchical curiosity with the means of production of images, ranging from the most artisanal to the most technological.

JH: Your work ‘To be Continued…(Latin American Puzzle)’ presents us with a giant map of jigsaw puzzle pieces. Each individual piece shows stereotypical figures, symbols of Latin America as found in tourist magazines. While the individual pieces are interlocking, the image they are portraying is not a continuous one. Can you speak about the figures you chose to include here and what they represent as a whole?

RS: ‘To Be Continued, o Quebra Cabeça da América Latina’ is a sort of touristic piece, in its “shallowest” sense, which maps the lack of knowledge concerning (the real) Latin America, through stereotypical icons of its history and culture. Unlike common jigsaw puzzles, the joining of its pieces does not form a more complete and coherent whole; on the contrary, it multiplies totally disconnected fragments – just like Latin America, in fact. That work was constructed based on the appropriation of images in tourist guides, publications by embassies and various magazines. It was a true operation of plundering and then choosing a myriad of fragments of images that signified the Latin American countries, within a very broad yet evidently incomplete historical spectrum. This is why the title begins with ‘To be Continued’: it does not end there, but will keep going on, like the telenovelas and serial novels. This was the first work in which I used digital printing.

Regina Silveira: ‘Destrutura executiva II,’ 1975, screen-print on paper, 52 x 69 cm // Courtesy of the artist

JH: Your four silkscreens appropriate images found in newspapers. Manipulated through geometric constructions spanning across the images, you are breaking down content, splitting it into new sections. Can you elaborate on the political content of this series?

RS: The images chosen are photos of politicians or executives, selected for their meanings linked to political and military power in that period. With their faces erased, the figures are not identifiable, that is, they were made anonymous—they compose military, executive and political situations that have thus been turned into generic situations. My primary aim was to apply perspective and geometric compartmentalization on the images in order to reveal the visual structures that organize them and manifest the idea of power. Overall, many of these series from the 1970s and early 1980s were denominated as ‘Executive Destrutures’, ‘Traps for Executives’ and so on.

Regina Silveira: ‘Rodovia Transamazonica,’ 2018, digital print, dimensions variable // Courtesy of the artist

JH: ‘Rodovia Transamazônica. Serie Brazilian Birds’ shows the image of the Transamazônica, the Trans-Amazonian Highway, which was built under the military dictatorship in the early 1970s and never actually finished. On top of the image you added the black silhouette of a bird together with black arrows marking its way of flight. Here, reproduced and zoomed in, the image originally appeared on a postcard. What role does the original take in this composition?

RS: The Transamazônica Highway, a highway of domination built to arrive at the borders of neighbouring countries, was swallowed by the forest. The bird that flies above the arrows on a diagram showing the flight patterns of vultures, which use air currents, was taken from an article in the magazine ‘Scientific American’, of that same year. For that postcard, which was part of the series ‘Brazil Today’ (1977), I simply thought it was a good association to put a bird of prey flying over the Transamazônica.

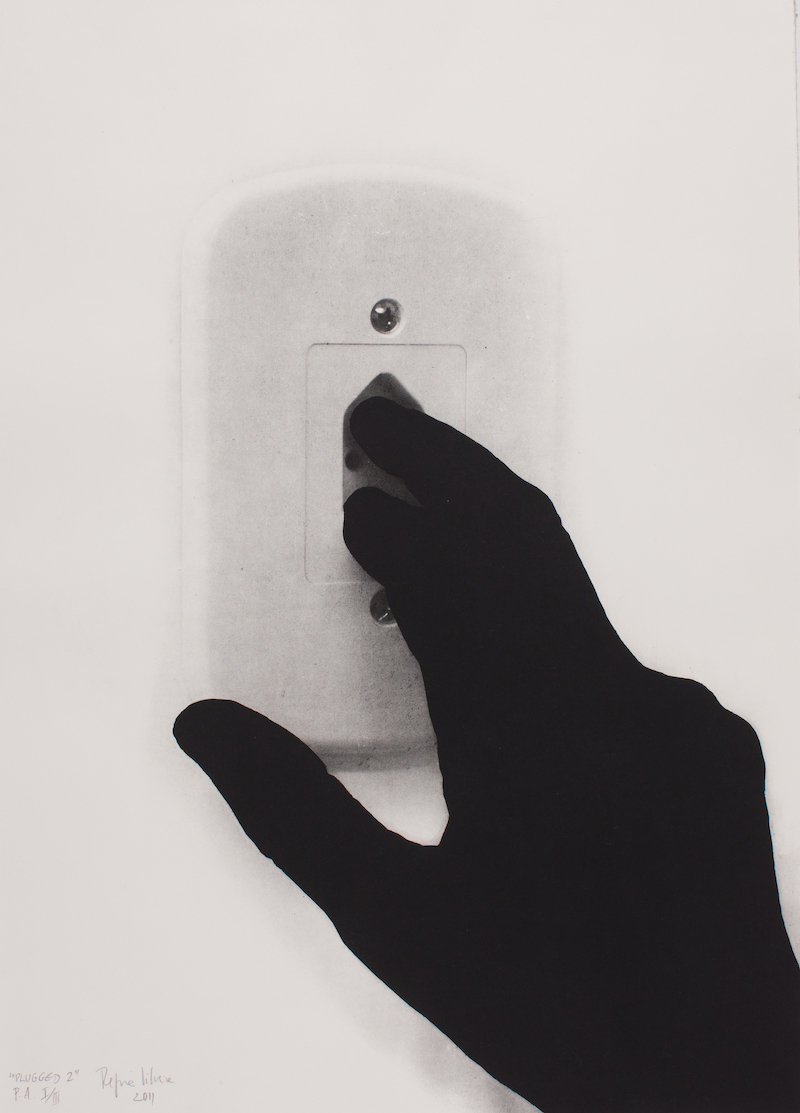

Regina Silveira: ‘Plugged 2,’ 2011, photo-etching, 66,5 x 47,5 cm // Courtesy of the artist

JH: For the three images of the series ‘Plugged’ you used photogravure, a process that requires a metal plate and etching to produce a positive photographic image. We see a black hand, almost like a silhouette, switching on a switch, holding a light bulb, reaching out for a socket. Light is a charged word, associated with modern knowledge and progress. What does it represent here in connection to the human that seeks it?

RS: This is one of the meanings that could be associated with those three prints, as well as the more existential enlightenment. The silhouetted hands are my own. The works of the ‘Plugged’ series were made at the printmaking studio installed on the ground floor of Fundação Iberê Camargo in Porto Alegre, as a special edition simultaneous to my survey exhibition ‘1001 Days and other Enigmas’ in 2010. For this exhibition the gigantic word LIGHT was a visual-verbal counterpart to these prints. Made in reflective adhesive vinyl, the word was applied over the façade of the Fundação building, where it reflected the light coming from the sky, the river and surroundings.