Article by Benjamin Busch // June 03, 2019

How to trace nonbinary relations at the Venice Biennale, an aging institution burdened by spatial subdivision into national domains of representation? With a queer transversal approach.

Queer transversality is a model of collectivity that combines queer subjectivity with a device for mapping the potential of desire within groups. For Félix Guattari, “Transversality is a dimension that tries to overcome both the impasse of pure verticality and that of mere horizontality: it tends to be achieved when there is maximum communication among different levels and, above all, in different meanings.” Group-subjects, according to Gilles Deleuze, “are defined by coefficients of transversality that ward off totalities and hierarchies. They are agents of enunciation, environments of desire, elements of institutional creation.” Transversality depends on an acceptance of the risk of having to confront “the otherness of the other,” of the multiplicity of desires espoused by groups outside one’s own.

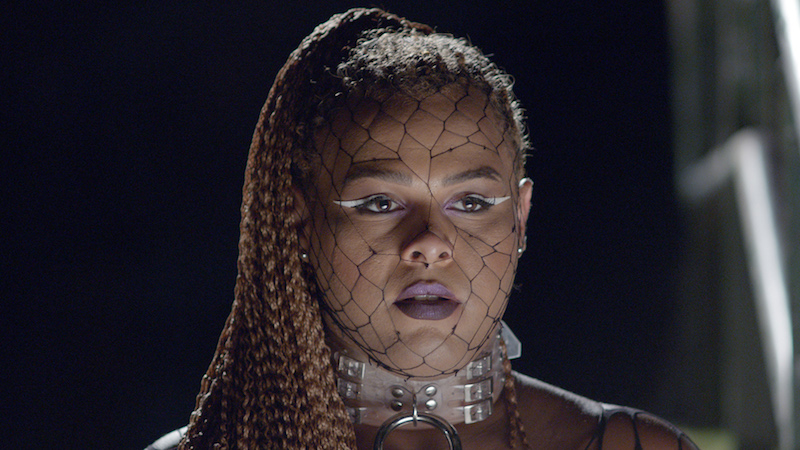

Bárbara Wagner and Benjamin de Burca: ‘Swinguerra’, 2019, still, Pavilion of Brazil at the 58th Venice Biennale // Courtesy of La Biennale di Venezia

Queerness implies a sensibility. Historically, queerness is linked to “Camp.” In ‘Notes on “Camp”’ Susan Sontag writes that Camp is a sensibility, not a hardened idea, and that “the essence of Camp is its love of the unnatural: of artifice and exaggeration.” Neither moralistic high culture nor high art, “Camp is art that proposes itself seriously, but cannot be taken altogether seriously because it is ‘too much.’ […] The whole point of camp is to dethrone the serious.” Camp confronts the normal as other, generating a perspective that accepts normality but also lays it bare.

Queer transversality can embody Camp, but the former is not necessarily defined by the latter. Contemporary queer expressions like drag, and particularly nonbinary drag, considered next to today’s more widespread genderqueer and transgender identities, challenge Sontag’s relegation of Camp to affluent societies “capable of experiencing the psychopathology of affluence.” An infrastructural sensibility, whatever its name, can draw relations between queer subjects across race, sex/gender, nationality and class. The trauma associated with queer experience, particularly that of adolescence, approaches something like a universal. Queer transversality accepts the risk of confronting the otherness of the natural and, as a mode of collectivity, unleashes queer desires.

Within this edition of the Venice Biennale as a whole, which comprises a curated international exhibition, the national pavilions, collateral events and a performance program, disparate queer facets combine to offer a multitude of transversal positions. Devised by Biennale curator Ralph Rugoff and Delfina Foundation director Aaron Cezar, a performance program during the early days of the 58th International Art Exhibition (to be supplemented with performances during the closing week) brought queer subjectivity and performativity to the fore. The curated performances, under the umbrella of the public program ‘Meetings on Art,’ unfolded on multiple stages, including several set up in the lush green Giardino delle Vergini, nestled behind the Arsenale.

boychild: ‘Untitled Hand Dance’, 2019, performance as part of ‘Meetings on Art’, 58th Venice Biennale, 2019 // Photo by Riccardo Banfi, Courtesy of Delfina Foundation and Arts Council England

Under dappled sunlight, Victoria Sin presented their work ‘If I had the words to tell you we wouldn’t be here now’ (2019), featuring Matteo Gemolo on the traverso, a Baroque transverse flute chosen specifically for the site of Venice. Sin, who is nonbinary, performed using elements of drag—costume, makeup, lip-syncing—to convey an extreme state of feeling. In a monolog presented as a disembodied voice, Sin repeats the phrase: “Naming is an act of mastery, and I would hope to never do that to you.” The pronouns and names of people and places in her story, broadly about gender identity and migration, are replaced with musical flourishes, forming a narrative that demonstrates how language both gives shape to and shapes thought. Sin’s own refusal of gendered pronouns (using instead they/them) reflects a practice of radical care: by refusing gendered pronouns, they open a space of queer transversality that does not presuppose or demand gendered subjects. At times during the performance, Sin’s amplified voice goes on without them lip-syncing, creating a rupture in the illusion of speech, a double estrangement that paradoxically brings the audience closer to their message.

Comparatively, boychild’s performance ‘Untitled Hand Dance’ (2019) was a subtle and heavily nuanced study in the gendered performativity of gestures. On a humble stage surrounded by grassy mounds occupied by an array of reclining audience members, boychild, wearing a two-piece suit, performed, without a soundtrack, an assemblage of loaded, empty-handed gestures. She covered a range of gentle, minute movements up to territorializing expansions across the space of the stage. Casting one’s gaze from her body toward the multitude of bodies in the audience, the fourth wall melted into the soil. For a moment, a fragile collectivity emerged around a tender space of queer transversality.

Florence Peake and Eve Stainton: ‘Apparition Apparition’, 2019, performance part of Meetings on Art, 58th Venice Biennale, 2019 // Photo by Riccardo Banfi, Courtesy Delfina Foundation and Arts Council England

In the Teatro Piccolo Arsenale, Florence Peake and Eve Stainton presented ‘Apparition Apparition’ (2019), in which their intimate relationship serves as a way to discuss personal and political stakes. Entering the theater, one encountered two nude women perched on seats in its center, drawing on each other’s bodies, with the stage curtain drawn. One by one, the artists asked members of the audience if they would consent to drawing on their bodies, with most agreeing. In a second phase, the curtain opened up, revealing a surreal scenography accompanied by a surging abstract noise soundtrack. The artists adopted various gestural and sexual positions amid partial objects, becoming one.

Housed in the Palazzo delle Prigioni, which was a prison from the 16th century until 1922, is ‘3x3x6,’ a new exhibition by Shu Lea Cheang, organized by Taipei Fine Arts Museum, Taiwan. Departing from research beginning with Giacomo Casanova, imprisoned there in 1755, Cheang presented the stories of ten prisoners from across space and time, cultures and histories, in the format of synchronized video portraits—prisoners accused of gender or sexual dissidence, including Marquis de Sade and Michel Foucault, among other contemporary cases. Meanwhile a large staged surveillance apparatus monitored and transformed images of visitors, imprisoning them in the machine.

Shu Lea Cheang: ‘3X3X6’, mixed media installation // Courtesy of the artist and Taiwan in Venice 2019

Curated by Paul B. Preciado, Cheang’s exhibition (and Peake and Stainton’s performance) can be read as works of queer postpornography. In his book ‘Testo Junkie’ (2008), Preciado writes that under today’s regime of “pharmacopornographic capitalism”—an extension of Foucault’s biopolitics in an era defined by pharmaceutical and pornographic consumption—postpornography is “a matter of inventing other […] forms of sexuality that extend beyond the narrow framework of the dominant pornographic representation and standardized sexual consumption.” People who have been “passive objects” of pornography become “subjects of representation.” In so doing, they undermine the codes that make their bodies and sexual practices visible as pornographic products for consumption, which feeds into an ideology of “natural” gender and sexual relations.

Among the national pavilions, Brazil and Switzerland, both in Giardini, offered two important contributions toward a transversal map of queer potentiality (while neither is explicitly postpornographic). The Brazil pavilion presented ‘Swinguerra’, a project by Bárbara Wagner and Benjamin de Burca, composed of a new film presented as a two-channel video installation alongside staged photographs of the film’s protagonists—predominantly queer and nonbinary dancers of color. The film accompanies rehearsals of three dance groups: a swingueira group, a brega group, and a batidão do maloca group—a series of movements and phenomena in Brazilian culture. In choreographed group scenes and individual communicative vignettes, the protagonists switch gender roles, expressing a fluid “gender performativity.” Throughout the film, the protagonists refrain from speaking: they communicate instead through movement; they move with booming music from the scene accompanied by arousing and provocative lyrics.

Bárbara Wagner and Benjamin de Burca: ‘Swinguerra’, 2019, still, Pavilion of Brazil at the 58th Venice Biennale // Courtesy of La Biennale di Venezia

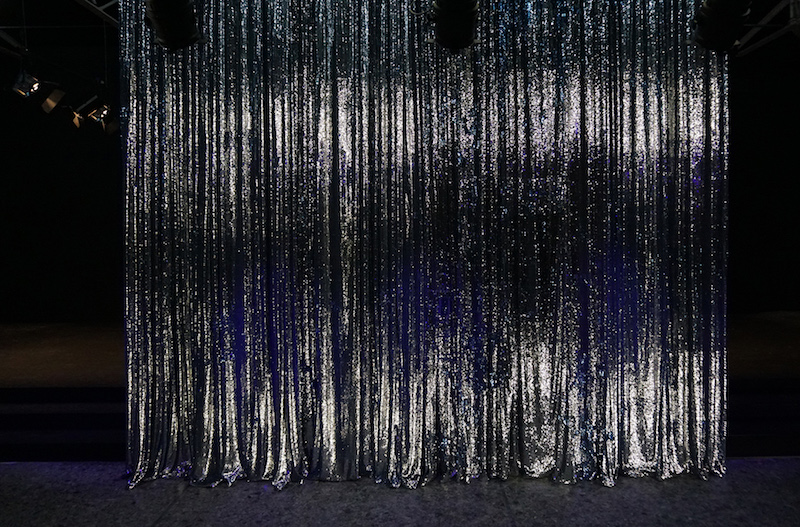

Finally, the Swiss pavilion, with the new work ‘Moving Backwards’ by Pauline Boudry and Renate Lorenz, suggests “backward movement” (as opposed to outright political opposition) as a potential tool for alternative forms of resistance and action in the current moment threatened by regressive and reactionary forces. Taking the form of a video installation, accentuated by an animate, sparkling silver curtain, this work also eschews spoken dialog, instead using visual identity cues and gestures of movement, gender performativity and queer collectivity. A takeaway newspaper available upon exiting the pavilion, presented on a bar next to two wall works, contains a dozen letters from influential international figures in queer discourse, printed in Arabic, French and English. The artists suggest a reorientation toward practices like those of the Kurdish Women’s Movement, bifurcated from the timeline of xenophobic authoritarianism.

These examples point to a future of queer art that is centered on the visual representation of subjectivities that have been hitherto deemed marginal, deviant, dissident, pathological. Important among these works is a de-emphasis on white, cis-male homosexuality, which has historically taken up a great deal of the “queer” space in artistic representation, compared to lesbian, bisexual, transgender, intersex and genderqueer subjectivities. Rather than static works, time-based media and performance prevail, interrogating through choreographic practice the everyday choreography of bodies and spaces generally perceived to be natural. Queer transversality explodes the natural order through a recognition and celebration of the many sexual practices and gender expressions that stand at the foundation of its own reproduction.

Pauline Boudry / Renate Lorenz: ‘Moving

Backwards’, 2019 (detail), Installation with film, curtain, stage, bar, publication and performances at 58th Venice Biennale, Swiss Pavilion // Courtesy of the Pavilion of Switzerland at the 58th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia

This article is part of our monthly topic of ‘Nonbinary.’ To read more from this topic, click here.

Exhibition Info

LA BIENNALE DI VENEZIA

Exhibition: May 11 – Nov. 24, 2019

Various Locations, Venice, Italy