Interview by Kimberly Budd // Oct. 15, 2019

Descriptions such as “anointed saint of contemporary Australian art” or “Australia’s most acclaimed living artist” attest to the kind of public profile Ben Quilty holds within the nation. As does the painter’s current touring retrospective, the kind of solo survey show normally reserved for famous international artists, or famous dead ones. Quilty’s extensive list of achievements include the most prestigious Australian portraiture award, the Archibald Prize, and a nomination for “Australian of the Year.” His painting practice and title as a social commentator and activist are bolstered by a fierce moral standing that results in a schism in popular opinion and critique.

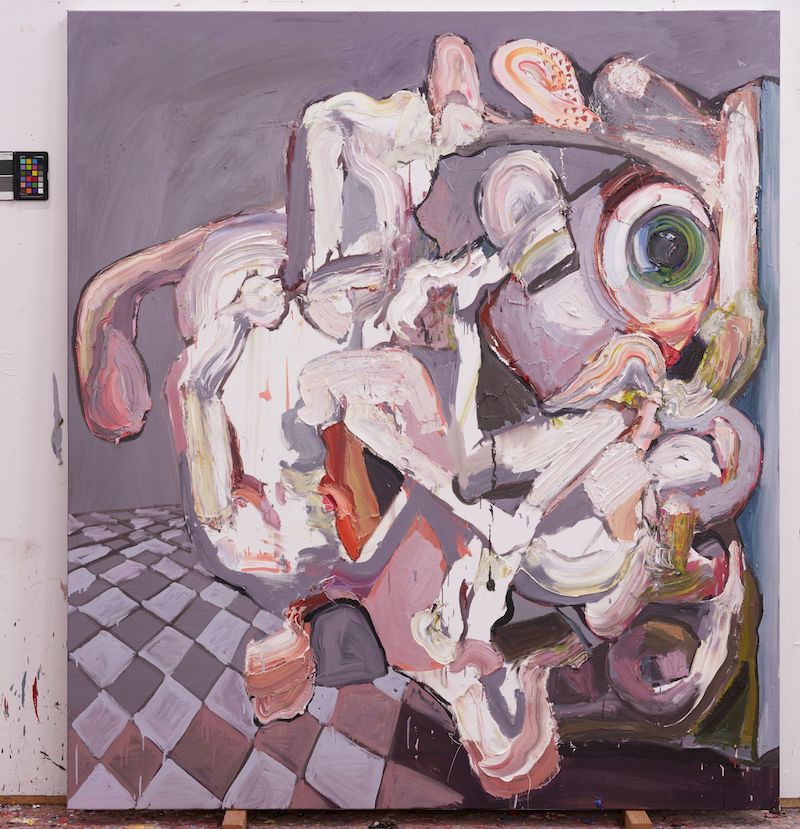

Ben Quilty: ‘A very awkward moment’, 2019, oil on linen // Photo courtesy of the artist

Emotionally-charged, Quilty’s practice has addressed social and political issues, including the human toll in war, life on death row, offshore detention, the refugee crisis, climate change and the massacre of Australia’s First Nations people. The passion for, and continuous commentary on, these issues, coupled with an outspoken and seemingly comfortable demeanour with the media, has positioned Quilty as a cultural spokesperson who has transformed popular opinion. There is, however, a conflicting position regarding the artist’s self-reflexivity and use of his very public voice and position. A recurring theme in Quilty’s, since his earliest paintings, has been a call of attention to the problematic nature of white masculinity in our culture and the unabating imbalances of power due to its supremacy. These criticisms have been chalked up to jealousy regarding his artistic success and fame, but there are those that genuinely question why the artist’s voice is so dominant in national debate, when it is exactly this position he interrogates as a problem.

The artist’s diligence as a painter is evident, as is his commitment to utilising his paintings to conjure an emotional response in his audience. He states that he hopes this turn may lead to greater empathy and a reassessment of our pressing cultural concerns. For his first solo show in Germany—’The Difficulty,’ currently on view at (A3) Arndt Art Agency—Quilty neither diverges from these integral moral motivations nor his definitive abstract expressionist style. We spoke with Quilty about the exhibition and some of its conceptual concerns.

Kimberly Budd: The title of your current exhibition, ‘The Difficulty,’ serves as an indicator for the conceptual content within this series of paintings. The difficulty of being, the difficulty in knowing how one should act or feel in the face of the world’s current political and environmental future and, perhaps, the personal anguish you experience when processing these ideas. Could you expand more on these subjects raised in this series, and express some of your main social concerns currently?

Ben Quilty: The works in ‘The Difficulty’ respond to my own anxiety about the world. I’m not sure how I can make art in 2019 without responding to the overwhelming sense of unease I feel about the world. Making art is meant to be difficult, as well. The more difficult I make it the more possibility there is of finding a new language. And, in 2019, it feels to me like we need to begin the process of creating a new language to describe the future of the planet.

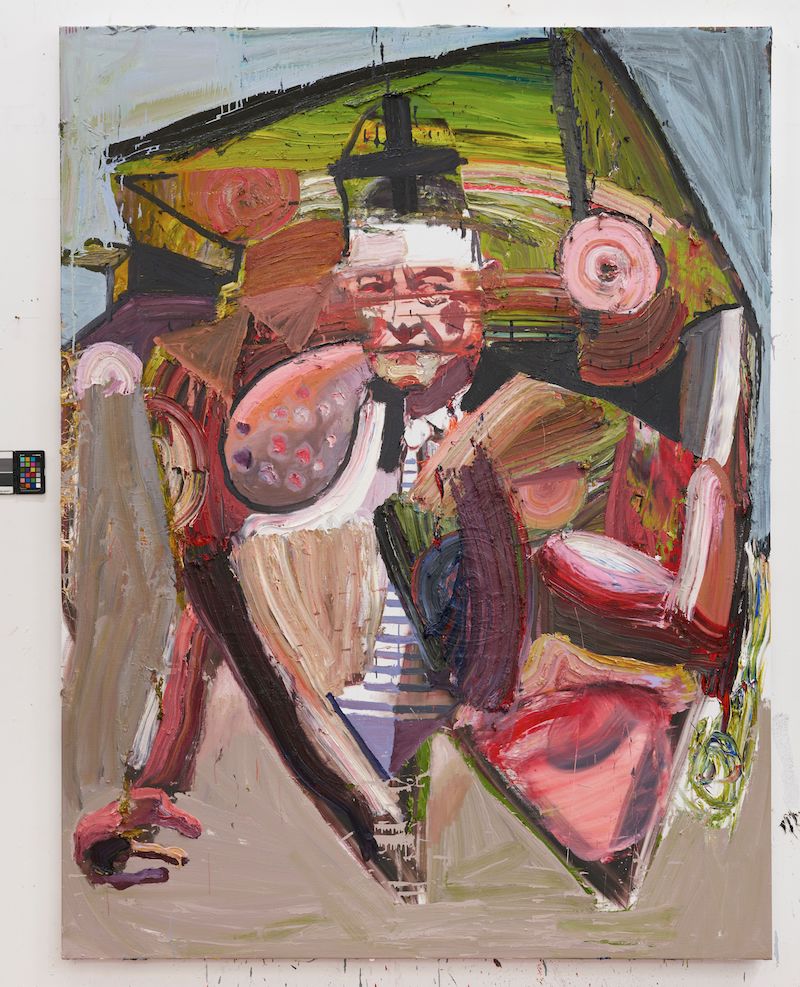

Ben Quilty: ‘The Racist,’ 2019, oil on linen // Photo courtesy of the artist

KB: The paintings are also critiquing, and actually feature, some of the men in power who continue to lead us into the Anthropocene. In your exhibition statement they are referred to as “your fellow men.” Is this an extension of your previous attempts through painting to spotlight the power and privilege the heteronormative white male continues to hold, and further examine your position in relation to this?

BQ: Yep. I’m a straight white man. My mum had three of them. I’ve often joked that the world would be better off without men. We are the humans that start wars, we crave power, we fight the wars and we have played a disproportionate role in the destruction of the world’s ecosystems. And I have a 13-year-old son.

I’ve learnt a huge amount about myself from my indigenous friends in Australia. They’re the oldest continuous race on the face of the Earth and they are also some of the world’s very best painters. Boys’ initiation ceremonies took up to 13 years; young men had proved their social status by successfully performing and enduring years of physical and emotional tests.

For me, I got drunk one night, my 18th birthday party, smashed, blind, ‘mother-less.’ And the next morning I woke up officially a voting adult. It’s dumb and it doesn’t work. I found making art was a powerful release for the unresolved lack of initiation, I guess. I’m part of the problem but I hope I can play a role in solving the problem, too.

KB: I heard you speak in a recent interview about the process of painting as venting for you. Was the creation of this series more of a personal, emotional catharsis, or was there strategy in how the paintings might be received and the social questions they may incite in the viewer?

BQ: This show is very much a personal response to my own feelings. Other times I’ve needed to be much more cognisant of an audience. I made a work about Australia’s brutal off-shore detention centres. It would have been irresponsible not to have been aware of the way an audience participates in a work like that. But for the past year I’ve had time to make work for no other reason but to make.

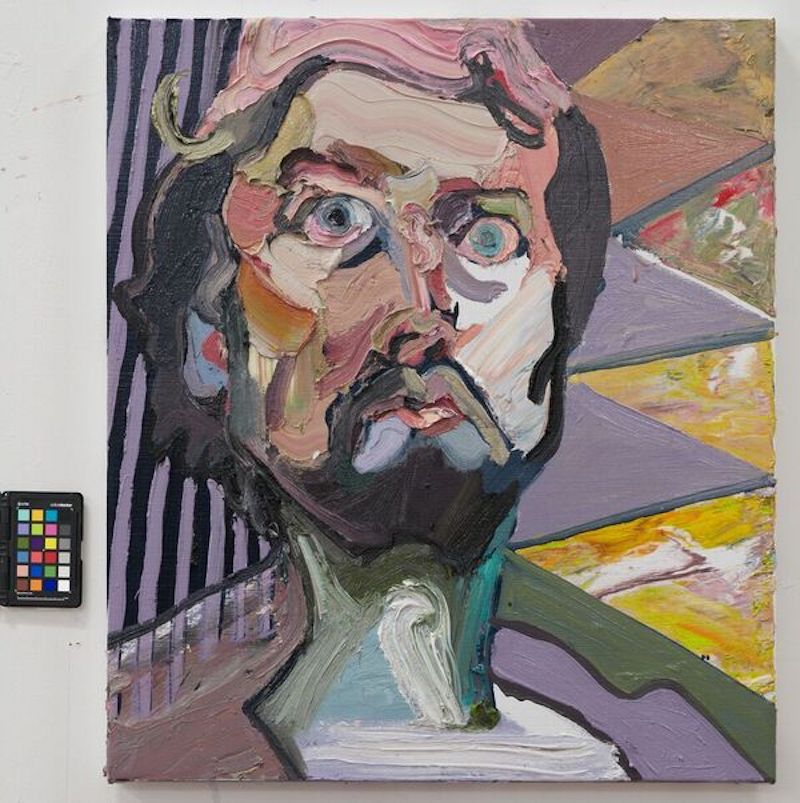

Ben Quilty: ‘An Angry Mob,’ 2019, oil on linen // Photo courtesy of the artist

KB: The 2019 Archibald Prize, which you won in 2011, has stated that this year they have a record number of contributions from and portraits of Indigenous artists. This seems like a very late but important step toward acknowledging the Traditional Land Owners in Australia. Your paintings ‘An Angry Mob’ and ‘The Racist’ are perhaps addressing this social-political landscape. Can you speak about how you address white supremacy and racism in your work?

BQ: While the Archibald Prize is on, the Art Gallery of New South Wales also exhibits the Wynne Prize for Landscape Painting and Sculpture. From a landscape like Australia, it’s been a shameful reflection of indigenous recognition that only one or two indigenous artists have been exhibited, until very recently. Now the masters of remote Australia have taken the prize for four years in a row and in my opinion are the most powerful part of the entire show. Half the finalists for the last four years have been indigenous, and most from remote communities. Nongirrnga Marawili, Yakultji Napangati, Sylvia Ken, Yaritji Young, Betty Pumani: their depth of creative talent is mind-blowing. But still, even within the art community, there are artists who claim that these artists do not belong in a “western” art museum. It’s shameful and that response is a symptom of a kind of social sickness. The very best and most unique part of my country is its indigenous history. And the painters who are winning the Wynne Prize are amongst the best painters on the face of the planet.

I try to face the fascists and white supremacists with calm respect. Racism comes from fear. Me being angry only increases the fear. So I do try to reach out and help calm things. But if another Australian Prime Minster announces that “Australia is not a racist country,” I’ll go mad. Besides Julia Gillard, all of our Prime Ministers have been straight white males.

KB: What advice would you offer for any upcoming artist whose conceptual focus and content is political? It seems as if having commercial success in the art world means leaving the strongly political works at the door, however you have had immense commercial success.

BQ: I’m not sure my political comments have helped my financial success. I recently read an article that suggested the opposite. But I’m only living once and I’m not interested in making pretty paintings to placate my audience. My favourite artists make huge political statements. All good artists of the 21st century are heavily political and socially aware. Saying that, it’s important not to starve. Becoming an artist is not easy. Make some work to sell and then make the work that you need to make to vent, perhaps?

KB: Was there a particular motivation for Berlin as a location for ‘The Difficulty’?

BQ: I met Berlin-based artist Ingo Gerken in 2003 at the Paris Cité des Arts on residency. And I promised him one day I’d get to his city. My friend Del Kathryn Barton also encouraged my friendship and relationship with Matthias Arndt. Matthias is willing to facilitate my madness and I love him for it.

Ben Quilty: ‘Upper’, 2019, oil on linen // Photo courtesy of the aritst

Exhibition Info

(A3) ARNDT ART AGENCY

Ben Quilty: ‘The Difficulty’

Exhibition: Sept. 05 – Oct. 18, 2019

Fasanenstraße 28, 10719 Berlin, click here for map