Interview by Denisa Tomkova // Nov. 01, 2019

The exhibition ‘Neither Black/Red/Yellow Nor Woman’ at Times Art Center in Berlin is based on the fictional meeting of three female protagonists: the novelist and artist Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, the painter Pan Yuliang and the filmmaker and literary theorist Trinh T. Minh-ha. The exhibition explores the notion of ethnic, gendered and diasporic identities, inspired by Minh-ha’s fundamental text ‘Woman, Native, Other: Writing Postcoloniality and Feminism in 1989.’ It opens up a critical dialogue on the position of the women who live, work and travel through different cultural, geographical and historical contexts and struggle for their identity and voices to be heard.

One example is Chinese modernist painter Pan Yuliang, who left China in the 1920s to study in Paris. Consequently, Pan Yuliang went through a transformation in Chinese collective memory from a forgotten artist to a mythical legend. Beijing-based art historian and curator Mia Yu explores Pan Yuliang’s story in her video work ‘A Journey from Silence’ (2017). For the exhibition at Times Art Center, Mia Yu departs from her usual role as an art historian and becomes one of the exhibited artists. We met Yu when she came to Berlin for the exhibition opening, and talked about the experience of living in diaspora. Yu expressed the urgency of storytelling that crosses borders and provides narratives from transnational perspectives.

‘Neither Black/ Red/ Yellow Nor Woman,’ installation view at Times Art Centre Berlin // Courtesy of Mia Yu

Denisa Tomkova: Your video work ‘Pan Yuliang: A Journey from Silence’ follows your personal journey searching for Pan Yuliang, one of the first modern woman artists in China, and weaves her transnational trajectory into yours. As an art historian and curator, what made you leave your usual role to become an artist?

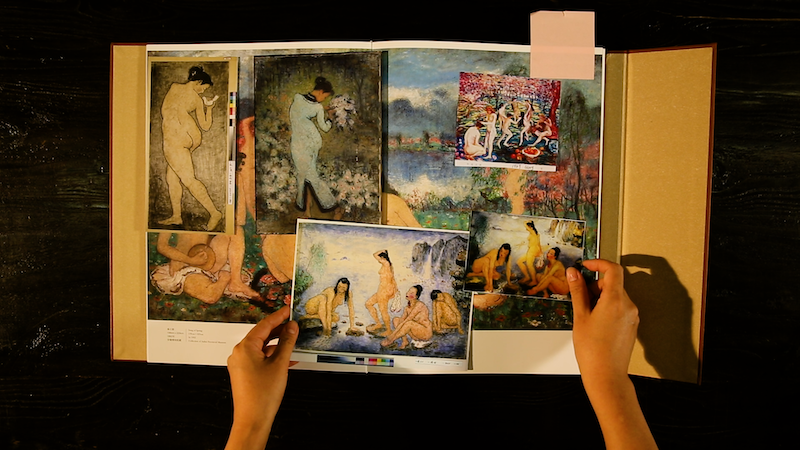

Mia Yu: I am always an art historian. I work on Chinese modern and contemporary art from a global perspective. I have never left this role. However, from time to time I employ the format of video essay to experiment with a different mode of art historical writing; that is, a visual narrative with images, voices and gestures and often animated through displaying archival materials. This is my attempt to address some of the theoretical questions in a more artistic and intuitive method. How can we conceptualize Chinese art, or Asian art in general, neither solely within national art history nor Western narratives and epistemologies, but through multiple and entangled histories and knowledge structures? How could transcultural exchanges provide new ways to understand the Chinese, the Asian and the global? For me, making video essays such as ‘Pan Yuliang: A Journey from Silence,’ is both an artistic challenge and an art historical challenge. To do so, I need to constantly push myself to the intersection between the artistic and art historical research and let scholarly, curatorial and artistic thinking and methods catalyse one another. The result is often a good surprise.

Mia Yu: ‘Pan Yuliang: A Journey from Silence,’ 2017 // Courtesy of Mia Yu

DT: Can you please briefly tell me about Pan Yuliang. What was her artistic career like?

MY: Pan Yuliang is an important Chinese modern artist. Despite coming from a low social class family, she became one of the first female students at Shanghai Art Academy in 1920 and managed to go to study in France. She studied oil painting and sculpture at various art academies in Paris and Rome during the 1920s. Upon returning to China, she taught in Shanghai and Nanjing as an art professor and actively participated in building Chinese modern art institutions in the 1930s. Having travelled extensively, she had a life filled with transnational trajectories between China, France and the United States. When she passed away in Paris in 1977, she left four thousand paintings, sculptures, sketches and unfinished works, which were repatriated to China in their entirety in the 1980s. What I found interesting about Pan Yuliang is not only the quality and the strength of her work but, more importantly, as a diaspora artist, she cannot be easily framed by art historical narratives. Her ambiguous position in the gap between multiple art worlds and knowledge structures triggers critical questions on how we can think of art history in a decentred way.

Mia Yu in front of her video work ‘Pan Yuliang: A Journey from Silence’ at the exhibition ‘Neither Black/Red/Yellow/Nor Woman’ // Courtesy of Mia Yu

DT: Why and how did you get interested in her life and work?

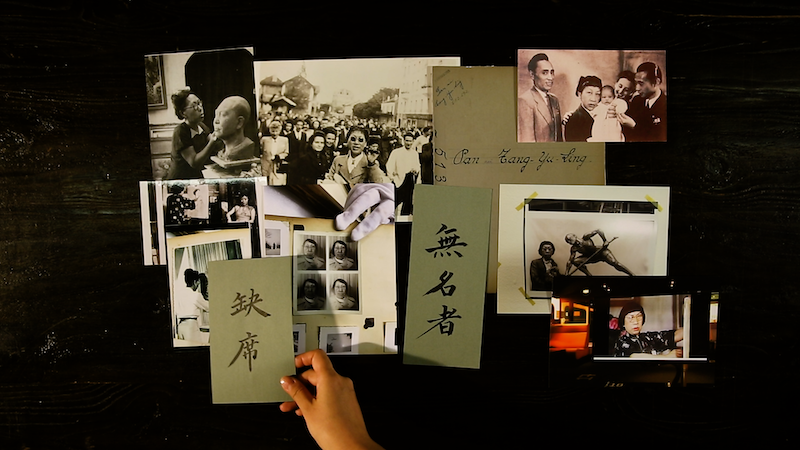

MY: My intense look at Pan Yuliang’s life and work started in 2017 when my friend Nikita Cai, the chief curator of Guangdong Times Museum, invited me to research about her for an exhibition. Together we visited various archives, museum collections and historical sites related to her memory. In Paris, we looked into the Marc Vaux archive, a massive photo archive that includes an enormous amount of photographs of diaspora Asian and African artists living in Paris from the 1920s to the 1960s.

However, due to the lack of knowledge about non-Western artists, these people were put in the category of “anonymous artists.” Pan Yuliang was also once put in this category. Her anonymity immediately intrigued me. Diaspora artists like her are often very prominent artists in their home countries, but they are irrelevant or “anonymous” to the Western modern art canon. In the case of Pan Yuliang, her figurative painting style makes her a misfit in the frame of Euro-American modernism. However, back in China, Pan Yuliang is also a difficult case. As a diaspora artist who spent forty years in France, she was never part of the leftist art movement, never involved in the doctrine of Socialist Realism and never participated in building art institutions under the Communist regime—all things that are important to the Chinese modern art history. She doesn’t seem to belong anywhere and yet inhabits multiple worlds at the same time. What do you make out of such disparity? How can misfits like her provide us with new entry points to rethink how art histories can be constructed differently? If the first keyword that I associated Pan Yuliang with is “anonymity,” the second key word I found is “silence.” Like many Chinese female artists I have researched, Pan Yuliang was shy when it came to talking about herself. As I went through her letters and journals, I found very little statement about her own art. However, I also found out that, shortly before her death, Pan Yuliang turned the opportunity to have her solo show at Musée Cernuschi into a group show for Asian women diaspora artists. Over and over again, I encountered dialectical tensions in her life: fame vs. anonymity, silence vs. action, the Chinese national art history vs. the Western modern art canon—all too complex to unravel at once.

Mia Yu: ‘Pan Yuliang: A Journey from Silence,’ 2017 // Courtesy of Mia Yu

DT: While doing research, what made you decide to tell Pan Yuliang’s story in a video format instead of writing an essay?

MY: Well, I didn’t decide to make a video right away. Although I was intrigued by her anonymity, her ambivalent silence and the problems of locating her in art histories, I didn’t know how to weave all my findings into one work until I encountered her “ghost” at the museum. It was a defining moment. In 2017, Nikita, myself and a few other artists went to Anhui Provincial Museum where her four thousand works and archives are currently being held. The museum is housed in an old Soviet-styled building located in an area of the city that is equally grey and uncharacteristic. Although the museum was closed for renovation, the collection manager allowed us to see the works in the storage. We were first led into a small waiting room lit by florescent light. A museum staff member came in and laid down a white polyfoam board on a table in front of us. We sat around the polyfoam board and waited and waited. It was very cold. As time passed, I felt we were participating in a collective ritual of calling back Pan Yuliang’s spirit. She could descend at any moment from somewhere above to the white polyfoam board in front of us.

Suddenly, we heard the elevator door open. A museum staff member pushed out a trolley. On the trolley was Pan Yuliang’s well-known self-portrait from 1939. She was there, being rolled out of the elevator, dressed in black cheongsam and holding a fan. The conversations suddenly stopped. We quickly gathered around the painting and looked at it closely. Her brushstrokes were so vivid and traceable that I could physically imagine her hand gestures while painting them. I looked at her eyes and her closed mouth. Her silent pose, imbued with a strong desire to speak, radiated in the room. The moment of silence seemed more powerful than any art manifesto. We were reminded of Gayatri Spivak’s acclaimed essay ‘Can the Subaltern Speak?’, in which she wrote “[w]hat the work cannot say is important, because there the elaboration of the utterance is carried out, in a sort of journey to silence.” Hence, silence emerged as a potent metaphor. Partly inspired by this experience, I made the video essay that is currently being shown at Times Art Center Berlin. Nikita Cai also curated the exhibition ‘Pan Yuliang: A Journey to Silence.’ As researchers of history, we know that ghosts have always inhabited the sites of archives, collections and the sites of memory. But they do not just appear; they need to be invited through curatorial and artistic enactment. My video essay is one such invitation.

Mia Yu and the research team encountered Pan Yuliang’s self portrait at Anhui Provincial Museum’s storage. // Courtesy of Hu Yun.

DT: You and I talked a lot about our diasporic experience as two art historians and women who come from countries which might still be considered ‘East’ by some people and work in the ‘West’ and write exclusively in English about our home countries’ histories. For me, diaspora is exactly this middle-land, this feeling like you have a home everywhere but nowhere at the same time. I find that the exhibition ‘Neither Black/Red/Yellow Nor Woman’ deals a lot with this diasporic feeling. It is an urgent exploration of women who have lived, worked and travelled through different cultural, geographical and historical contexts and struggled for their identities and voices.

MY: I returned to Beijing ten years ago after having studied at McGill University and living in Canada for a long time. Coming back to my own country, I intentionally kept my mind in a diasporic mode. I think diasporic identities do not just belong to those who live abroad, but are rather a critical positionality and attitude. As an art historian, I choose to adopt neither China-centric nor West-centric approaches, rather to fully acknowledge the complex conditions and processes from which the so-called “East” and “West” are mutually constituted.

Back to Pan Yuliang: I think throughout history, there are extraordinary women like her who searched for their own voices while crossing multiple boundaries of class, gender, race, nation and other historical barriers. Their lives inspire me. I am also so delighted to see that the exhibition ‘Neither Black/Red/Yellow Nor Woman’ is informed by the conceptual re-enactment of works and archives of three inspiring Asian women artists: Pan Yuliang, Theresa Hak Kyung Cha and Trinh T. Minh-ha. The two curators, Nikita Cai and Xiaoyu Weng, have composed an imaginary encounter between these three artists in the Montparnasse Cemetery sometime in 1979. The imagined encounter is used as a visual and conceptual metaphor in the exhibition to link the border-crossing journeys of various female artists together. It is through the stories, the images and the voices of these women that we could collectively challenge the identitarian politics and the antagonistic dichotomy that haunts our relationship with the past, present and future. Their stories are also my stories.

Mia Yu: ‘Pan Yuliang: A Journey from Silence,’ 2017 // Courtesy of Mia Yu

DT: The exhibition is conceptually inspired by Trinh T. Minh-ha’s fundamental text ‘Woman, Native, Other: Writing Postcoloniality and Feminism in 1989.’ Why do you think this text is still so relevant today?

MY: I think that, in today’s milieu of socio-political divide, an aggressive global expansion of identitarianism increasingly penetrates our daily lives. Back in 1989, Minh-ha had already proposed a non-dualistic affirmation of identity, which was radical back then but also highly relevant now. More than ever, we need border-crossing storytellers to narrate worlds from their situated locales and to generate new knowledge from trans-dualistic perspectives. As an art historian, what I can do is continue to tell the stories of transnational artists in the format of the video essay. And I don’t care if some people may say “this is not serious art history.”

Mia Yu: ‘Pan Yuliang: A Journey from Silence,’ 2017 // Courtesy of Mia Yu

Exhibition Info

TIMES ART CENTER

Group Show: ‘Neither Black/Red/Yellow Nor Woman’

Exhibition: Sept. 28, 2019 – Jan. 04, 2020

Brunnenstrasse 9, 10119 Berlin, click here for map